Closing the Gap: How FUHSD addresses disparities in special education

Examining how the district accommodates for students in special education

March 30, 2022

FUHSD accommodates for students in special education academically and socially

Exploring the methods the district uses to bridge the achievement gap

Across FUHSD, students in special education make up 9% of the student population. At MVHS, this number is 5%. Students in special education can face barriers when trying to integrate into the traditional school setting — an issue highlighted by the disproportionate amount of failing grades they receive in comparison to their general education peers.

FUHSD Director of Educational and Special Services Nancy Sullivan has been trying to bridge this achievement gap through changing support services and emphasizing getting more students into general education classrooms.

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), students in special education are entitled to Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), which are blueprints that map out each student’s support system. To be eligible, students need to have one or more of the 13 disabilities listed in the IDEA.

Most students with IEPs earn a high school diploma upon graduation, but those with alternate curriculums earn a Certificate of Completion instead. Students with 504s, which are those with any disability such as asthma, are not considered special education and not part of the IEP population, and they make up 4% of the district and school.

Based on statistics and experience, Sullivan understands that students in special education who learn in a general education classroom tend to do better academically. However, she acknowledges that it’s sometimes hard for students to keep up with the pace of the class, which Sullivan and the rest of the special education staff address through various methods, including implementing accommodations and modifications for students with IEPs.

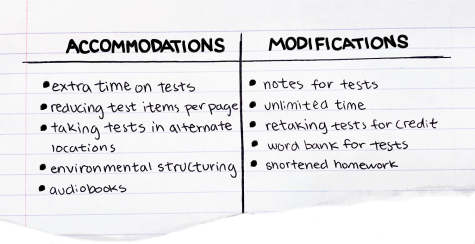

Accommodations are adjustments provided to students that do not change the standard of the class such as extra time on tests, reducing the test items per page and taking tests in alternate locations. Modifications, however, do change the academic standard of the class and include notes for tests, unlimited time and retaking tests for credit. Both accommodations and modifications are implemented in general education classes and lead to a diploma, however modifications remove the college eligibility for the course.

To ensure they’re providing the necessary accommodations, general education teachers are notified of students with IEPs in their class and what that student needs in order to be successful. This ensures that the teacher understands that student’s support system and how to implement it in their classroom.

“Let’s say you have a student in AP Chemistry and they have an accommodation that gets them 50% extra time on tests,” Sullivan said. “That teacher has that information and as they’re getting ready for the test, there’s communication or a system put in place, so that that student has access to additional time. It could be that they start the test and stay in the class and finish it at that time, or come earlier before and after. And sometimes it’s really simple [and] sometimes it’s very complicated. So there’s collaboration that happens amongst special education staff [and] they make sure [the student and teacher are] working together.”

The special education department has been trying to increase collaboration with general education teachers, according to Sullivan. One method Sullivan suggests is co-taught classes where general education and special education teachers teach a general education class together or a “push and support” method where special education teachers go into a general education class and help students along with the general education classroom teacher. As a Special Education Testing Coordinator, Ceazar Agront is responsible for knowing and providing accommodations during tests and quizzes. Agront works as a “figurehead” with general education teachers in some classrooms and communicates with the teachers to see where they need support.

“There’s always been a significant amount of collaboration between general [education teachers] and specialists,” Sullivan said. “But now, it’s trying to make sure that we’re really [giving] what students need in order to be successful. We’ve been looking at the training that teachers are getting through curriculum leads, making sure that we’re considering differentiation strategies and universal design when they’re thinking of lesson planning.”

The special education department has a diverse set of staff to ensure each student’s support systems are met. To understand a student’s necessary arrangement, the special education team tries to get to know them well, developing a list of supports which are then provided to all staff — which includes special education teachers who serve a range of disabilities and specialists who only support a certain area or need. Paraeducators make up the largest proportion of the special education staff, providing support for teachers through personalized help with the students in their classrooms. Agront is also one of the 100+ paraeducators working for the district and is responsible for understanding which students need which accommodations and making sure the supports are actually being utilized, helping the student “come back full circle and feel supported.”

“There’s so many different types of supports [and] it’s awesome because it means that the bar [isn’t necessarily] set so high,” Agront said. “[So] all the students that might have special needs or might have learning disabilities have supports that can help them bridge the gap.”

Since IEPs are individualized, Sullivan says she has been trying to equip staff with as many tools that they can apply in different classes. This has been challenging since “what works for one student may not work for another student.” Agront understands this challenge.

“Each student comes from a different background,” Agront said. “Although [they] might be similar in age and [at] similar parts of [their lives], everyone handles life differently. Being able to learn how to maneuver through all that and really get to know a student and provide support is the biggest thrill [of my job], but it’s also a challenge because sometimes it takes longer to build that bond with the student, all the while seeing the students struggle and [I’m] trying to figure out how can I help.”

During the pandemic, building personal connections was more challenging over Zoom, according to Sullivan. Additionally, COVID posed unique challenges to students with significant needs such as those who needed specific stimuli that couldn’t be done remotely. It was also especially hard for staff to provide support over a screen, which led Agront and other paraeducators to focus more on a student’s emotional well-being rather than their academic performance.

“Kids that sometimes have special needs are learning how to swim through their own emotions,” Agront said. “And they can have pitfalls and they feel a certain type of way and they regress. And [I] saw a lot of that — that was the biggest thing, just not being able to be in person and talk and feel like you weren’t alone, I think that was a huge detriment to our students.”

When half of FUHSD students in special education returned to in-person learning in the fall of 2020, the staff reviewed each IEP and added additional support to fill in gaps, helping students catch up as much as possible in terms of both academics and reforming staff connections. This meant slowing down the pace of some classes, similarly to how general education teachers did in the fall of 2021. Agront understood the emotional toll COVID had on his students and “did everything underneath the sun to make sure that they felt that this is still their home [and] they can still come to us for anything.”

FUHSD also has specialized classes for students who are struggling in certain subjects, allowing them to learn at their own pace and through applied methods such as repetition, practice feedback and hands-on activities — with the goal of transferring to general education.

“For the academic classes, it may not look much different than the process that [general education students] are in,” Sullivan said. “The exact amount of topics that get covered might not be the same, but other things are the same. So they might be doing a warm up at the start, they might be reading a book together that [is being taught] in literature or they might be working on essays or practicing speeches.”

However, in contrast to those with IEPs, students with an alternate curriculum learn in classes that are structured differently than general education classes. These classes still cover basic skills such as reading, writing and math but at different levels. For example, if freshman literature classes are reading “To Kill A Mockingbird,” those with an alternate curriculum will read different literature at an adjusted skill level, but they will still practice comprehension and writing skills.

MV Ohana Club also helps support students in special education with social connections. The club bridges special education and general education students together in a safe environment with activities such as kite-making and scavenger hunts. Ohana Club Secretary and junior Joyce Lui thinks the club helps make special education students feel more welcome at MVHS, especially those who don’t have many opportunities to interact with general education students. Lui reflects on how being in the club helped her be more aware and patient.

“There might be one student in the club who’s really closed off and they don’t really want to engage in activities,” Lui said. “And maybe there’s this one student who’s super hyper and you might need to help them ground and tone it down. I think [being in the club] has helped me with my awareness and just being more compassionate towards others.”

Agront thinks the intense culture at MVHS can exacerbate challenges for special education students, because this leads them to feel more pressure. Sullivan agrees and thinks the MVHS culture acts as an extra layer on special education students and understands the emotional distress it can create.

“Students that have IEPs can go from the most high-performing student you could imagine to the student who [is struggling] the most,” Sullivan said. “And I think there is often some disconnect with the feeling that ‘I have this disability and I’m having to work so hard, and I’m already working so hard, and the person next to me is doing so much better, even though I’m working so hard.’ So there is a frustration that some of our students have felt and it can be a very emotional and frustrating situation.”

But “in their back pocket” is the support that Agront and others provide to help give them a fair shot, and for Agront, seeing his students overcome this feeling is rewarding. Sullivan thinks the MVHS team is “great” in helping special education students not only with support, but also in coping and persevering through discouragement.

Sullivan understands the challenge in providing equitable educational opportunities for students in special education through the general education setting. For her, the push is a “pretty complicated system with a lot of moving parts.” She praises the special education team for contributing to the constant process of moving forward for these students.

“I would like to say special education staff, whether teachers or paraeducators, are probably some of the most hardworking staff,” Sullivan said. “They dedicate themselves to helping students be successful and feel successful. And I would say that, particularly during the last two years, it’s been extremely challenging to be a special education teacher. So I would commend [the] team in MVHS and any of the teams in our district for persevering and keeping students at the forefront of their minds. I think we’re very lucky to have the staff that we have in our district; they really do want students to be successful and they’ve been tasked with a pretty large amount of work. So I commend them.”

The overrepresentation of minority students in special education prompts state-wide action

Examining how the district is addressing racial discrepancies in special education

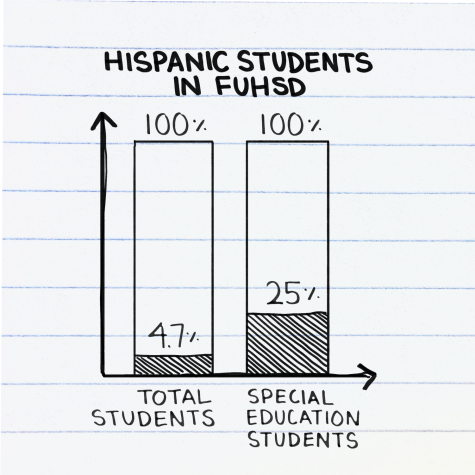

For the last three years, FUHSD has been classified as significantly disproportionate in special education by the California Department of Education, meaning that students from a particular racial or ethinic group — in this case, Blacks and Latinos — are identified as special education at a greater rate than other racial groups.

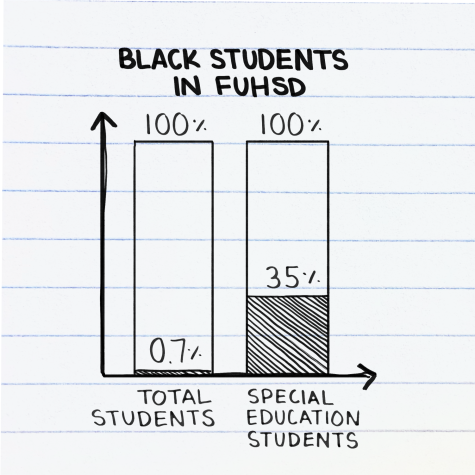

According to the significant disproportionality report published by the board, in the 2019-2020 school year, 4.7% of students in FUHSD were Hispanic and 0.7% were Black. However, in special education, 25% were Hispanic and 35% were Black.

FUHSD has implemented a plan from the Comprehensive Coordinated Early Intervention Services or CCEIS, that intends to address this overrepresentation specifically by asking volunteers to take professional development on “culturally responsive teaching.” The months-long PD asked staff to go through a process of looking at current teaching practices and acknowledging inequity in how they address diverse student groups. This emphasizes teaching styles that focus on relationship building and helping students feel engaged and understand that they can make mistakes.

The plan is divided into four phases: “Getting Started,” “Data Discovery and Root Cause,” “Planning for Improvement,” and “Implementing, Evaluating and Sustaining.”

Phase one, “Getting Started,” focuses on data collection by the CCEIS leadership team, which consists of eight members who are responsible for developing a plan and monitoring implementation.

Phase two, “Data Discovery and Root Cause,” uses this data to draw trends. In 2020, 72% of Black and Hispanic students with specific learning disabilities had an IEP when entering the district. The team found that Hispanic students were overrepresented in intervention classes, and Hispanic and Black students were underrepresented in AP and Honors classes.

Through data analysis and discussion with various stakeholder groups, the team decided to focus on two root causes for this disparity: inconsistent practice in intervention and implicit bias on cultural factors in classes and assessments.

The team found that there is an inconsistent application of the Multi-Tiered System of Support intervention strategies across the district. Although schools have lists of intervention systems, they do not have a systematic review process that includes comprehensive data collection, which means that the schools and even individual teachers were practicing different intervention strategies.

The data also revealed that Black and Hispanic students have higher rates of absenteeism and lower rates of academic achievement compared to their classmates in FUHSD, forming an achievement gap most prominent in reading. Hispanic and Black students had an absentee rate of 23.2% and 13.3% respectively compared to their white and Asian classmates that had a rate of 9.5% and 2.9%.

This educational discrepancy leads the staff to implicitly lower standards for Black and Hispanic students and increasingly refer them for special education assessment. The root preconception is also reflected in the general school environment: the enrollment rate of Black and Hispanic students in Academic Foundation classes is significantly higher than in Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID), and research found that the Academic Foundations class is seen as for failing or struggling students while AVID is seen as a support class for those capable of going to college.

Comments from parents contributed to the research:

“My son struggled with reading comprehension and it needed improvement,” one Hispanic parent said. “The teacher assumed that my son didn’t care about his future and learning. The counselor said maybe he needs special education.”

“My son is very energetic,” another Hispanic parent said. “The first thing they want to do is ‘Let me help you.’ No other alternatives, to try other strategies. The medication, every time the physician would offer me the medication.”

“The narrative the parents are told, the narrative the students are told, ‘You are not going to college,’” one Black parent said. “It is unfair that we have to prove we are worthy of success.”

“One [staff member] said out loud to my son, in front of me. ‘You are not going to college,’’ another Black parent said. “She could not see how hurtful those words were to him and to me.”

FUHSD administration is attempting to address this issue through creating equity task forces at each of its schools, but according to the report, not much progress has been made so far.

Phase Three, “Planning for Improvement,” focuses on a review of policies, practices and procedures, creating focus groups and measurable outcomes to address the root causes identified in Phase Two. The main goal is to increase academic achievements for ninth graders in Literature & Writing and Algebra 1 who were previously failing or who qualified for other criteria such as chronic absenteeism. At Fremont High School and Homestead High School, these focus groups are put in culturally responsive classrooms and their progress is tracked by the leadership team.

Phase four, “Implementing, Evaluating and Sustaining,” is a continuation of phase three and focuses on implementing an action plan. This means collecting, analyzing and presenting data to stakeholders on a quarterly basis. At stakeholder meetings, members discuss implementation plans and evaluate the impact it had on focus groups. Once the impact is determined, future funding will be considered.

—

To learn more about disproportionality in special education:

Significant Disproportionality in Special Education: Current Trends and Actions for Impact: https://www.ncld.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/2020-NCLD-Disproportionality_Trends-and-Actions-for-Impact_FINAL-1.pdf

Identifying the root causes of disproportionality: https://paperzz.com/doc/7528733/identifying-root-causes-of-disproportionalit–brief-

Unconscious Bias: When Good Intentions Aren’t Enough: https://www.responsiveclassroom.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Unconscious-Bias_Ed-Leadership.pdf

Distinguishing Difference From Disability: https://spptap.org/distinguishing-difference-from-disability-the-common-causes-of-racial-ethnic-disproportionality-in-special-education-pdf-outside-source/