Gross explains the Title IX reporting and investigation process

April 22, 2021

After a Title IX violation or other sexual misconduct-related misdemeanors are reported, staff respond by investigating the incident and consulting Gross. Sometimes, cases are dealt at the school level, but for more serious violations like sexual harassment and assault, Gross opens an investigation and formally informs all families — even if the students involved are 18 — about the investigation and the Board policies. These investigations are conducted using the district’s Uniform Complaint Procedures and follow either the sexual harassment or Title IX policies.

Gross explains that the main part of investigations involves interviewing, particularly with the typically two people who are directly involved in the situation that allegedly involved non-consensual touching or assault.

Gross adds that the district sometimes receives and utilizes social media screenshots to add context for certain situations, or in cases of cyber sexual bullying, provide “some level of evidence” for “exchanges that were inappropriate or pictures that were posted.”

All sexual assault or rape allegations are reported to the police, and after the police are contacted, the police and district carry out two separate, confidential investigations, and do not typically collaborate or communicate extensively about their respective investigations. Gross is in charge of the FUHSD investigations, and communicates about progress and next steps with all students, families and staff involved. Currently, Gross says there are two ongoing investigations at MVHS and the police have been contacted as well.

Gross explains that the district investigation is guided by Board policies and the California Education Code, whereas the police investigation is guided by legislature. If the police investigation results in a citation for the student (such as in the case of sexual battery), then the district will also implement consequences for the perpetrator.

“Sexual battery is an Ed Code violation, and if [the perpetrator is] proven to have engaged in that, and if it has a connection to school and it’s impacting the survivor’s ability to make progress in school, feel comfortable and safe, then there will be discipline,” Gross said. “In some cases, the far extent of that discipline could be recommendation for expulsion — there’s a hearing, there’s a whole process to determine that. Also sometimes, the incident that occured might not also be a crime, so then we would only be guided by the district’s internal investigation process, and then we have policies like the Sexual Harassment Policy which makes it very clear that a student would violate that policy if they had done things such as non-consensual touching. Part of what I do when I initially get a report is I gather the information that a site initially has, and make a decision about how I’m investigating and which policies I am using.”

If an investigation reveals that the perpetrator is guilty, the district implements corrective actions. One of these corrective actions could be a no-contact contract, which includes constraints regarding how people move about campus in order to limit contact. These actions may also include suspension or expulsion. In the case of expulsion, the district remains responsible for the expelled student’s education — they would go to a different program during the term of their expulsion, and after completing that term, they may consider attending a different high school within FUHSD.

“I have also changed schedules, changed classes,” Gross said. “One of the questions I’ve been asked recently is — how do you determine which corrective action goes to which issues? And it is kind of hard to say because they’re all very different, but I would say the bottom line is, the goal is that, if that policy has been broken, we need to create an environment for the survivor that provides them with the safe and healthy ability to be on their campus and participating in school without impact. The corrective actions are really connected to making sure that we can make that happen.”

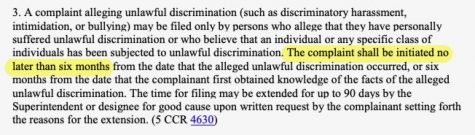

Another concern that Gross has been hearing recently from students pertains to language present in FUHSD’s Title IX policies stating that “the complaint shall be initiated no longer than six months from the date that the alleged unlawful discrimination occurred, or six months from the date that the complainant first obtained knowledge of the facts of the alleged unlawful discrimination.”

Gross says she has investigated several cases that are older than six months, and explains that the language likely stems from required legislation but that the district does not follow it strictly. After hearing this concern from students, Gross reached out to one of the district attorneys who has expertise in Title IX legislation to have a conversation about it, and says she will be clarifying this with the community soon. If it turns out that the six month language needs to be kept in the policy because it is a legal requirement, Gross plans to make additions to the website explaining that even if an incident is older than six months, it should still be reported, “because the last thing I want is for people not to report” and “people are reporting things that are older than six months and we have investigated those.”

“I do feel like we have a very complete process in terms of how we handle these situations,” Gross said. “The thing for me is making sure that people know they can and should report. Sometimes what we hear is that the school or district is doing nothing. I think that some of that comes from the fact that there’s things people know, but they haven’t been reported so we can’t follow up on them — we can’t do anything if we don’t know about them. And it’s also having the students understand the reporting process, how we can provide support.”