FUHSD participates in Culturally Responsive Education training

Nine MVHS staff members take part in a 5-month-long online course with FUHSD

When FUHSD hires a new teacher, Coordinator of Academic Interventions at FUHSD Josh Maisel and his new teacher mentor team support newly hired teachers and guide them to align with the district’s values through reading the foundational book “Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain” by Zaretta Hammond. In August of 2020, Hammond launched a month-long online course called Culturally Responsive Education by Design, which Maisel and his team started immediately.

According to Maisel, FUHSD has significant racial disproportionality in its special education classes, where the percentage of Black and Latinx students taking these classes is significantly higher than the proportion of Black and Latinx students in the district. To address this, Maisel and his team are piloting programs at schools with more Black and Latinx students, specifically to help freshmen in general education classes so that they’re not unnecessarily redirected into special education later down the road.

Culturally Responsive Education by Design was meant to prepare teachers for one of these programs at Fremont High School and Homestead High School. Maisel and his team made the course available to all FUHSD staff from January 2021 to June 2021, of which 40 signed up. Staff members at MVHS who are taking it are math and science teacher Sushma Bana, library media specialist Doreen Bonde, English teacher Mark Carpenter, art teacher Brian Chow, Principal Ben Clausnitzer, English teacher Stacey Cler, Assistant Principal Nico Flores, science teacher Kavita Gupta and journalism adviser Julia Satterthwaite.

Maisel says that the course is “for people who have done a lot of the preliminary work around identity and implicit bias and the foundations of anti-racism.” The course outlines the definition of independent versus dependent learners and how teachers can develop self-awareness. Maisel believes that the purpose of high school education is to make students independent learners in order to set them up for success in college and beyond — a focus teachers should have to best support students in general education classes.

“An independent learner can read a textbook and get the information that they need out of it to pass the test,” Maisel said. “Whereas other people, in certain contexts — and again you could be independent in an English class but more dependent in a math class — dependent learners, when they face a problem, they freeze, and they wait for the teacher to help them. And they can’t access the resources and the strategies that are available, because, for whatever reason, those conditions aren’t right for them in that class.”

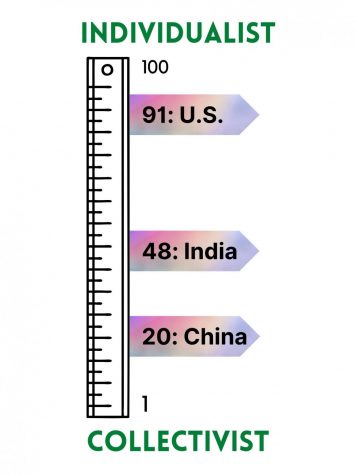

“Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain” also defines individualistic culture, like “pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” as Maisel describes it, compared to collectivist cultures, which value community and relationships more than individual achievement. The book classifies countries on a scale from collectivist at 0 and individualistic at 100: U.S. at 95, India at 48 and China at 20. Maisel seeks to use these definitions to learn about deep cultural roots and information processing patterns that make up different learning approaches. These are due to cultural differences with teachers — a large proportion of whom are white, middle-class and come from an individualistic culture, according to Maisel.

“What this has shown us is culture is not what we thought it was,” Maisel said. “It’s not about the holidays and clothing; it’s much, much deeper. And as white educators, if we want to really serve all of our students equally, we have to find a balance in the way that we’re teaching. Because when you get to high school, you’ve already had 14 years, especially the first seven years when you’re in your home, the way that you’re learning and the way that you’re processing information really depends on your home culture, that nurture culture. And if you come to a school that doesn’t understand that, and it’s teaching in a different way, there’s just much, much more difficulty in the brains of those students to capture the same information and to be able to develop the same skills.”

Maisel emphasizes awareness and perseverance with these new concepts and says “as long as someone’s race is an indicator of their success in our district, we’re not there yet.” The course itself also challenges staff to persevere through challenging self-paced content during distanced learning with the support of collaborating with other teachers at MVHS and FUHSD. Both Gupta and Clausnitzer have found the course a time-consuming and meaningful process.

“I’ve enjoyed it, in terms of some of the thinking that goes beyond maybe what education is doing, in the world of diversity and equity and inclusion, where a lot of the work is this work of self-awareness, which is good work and necessary work,” Clausnitzer said. “And then, there’s the world of ‘I’m a teacher in a classroom, how do I go deeper into what’s occurring in my class?’ to actually have impact and empower the students to get to a place where students are empowered, and that type of conversation has been really interesting for me.”

One concept that was interesting to Gupta was productive struggle — illustrating the journey of a learner as a pit, which Gupta describes as where the learner goes from “feeling totally, overly confident to ‘My god I don’t get anything,’ and then comes out of it on the other end feeling confident and knowing.” Along the lines of supporting students in the “My god I don’t know anything” phase, Gupta has learned about avoiding over-scaffolding, or watering down difficult concepts for struggling students, and instead being intentional about leveraging relationships between teachers and students to increase student confidence. In class, she finds herself asking herself which of her practices she can change.

“Today … I told students, ‘This is a complex [chemistry] concept,’” Gupta said. “‘It’ll take some time for you to become masters at it so don’t expect that by Tuesday when I see you next you will know it inside out, but together we will get there.’ So, what [the course] is doing for me is just bringing intentionality to the work that I was doing, bringing focus and also reframing a lot of things and looking at my teaching through a different lens and just being critical and evaluating.”

In turn, Maisel recognizes a “culture of compliance” at FUHSD schools, where students focus on completing work and following directions rather than focusing on learning and comprehending the material. Maisel wants to upend that system, suggesting that students look at feedback not to get more points, but to improve their skills. He recognizes this is a difficult change to make with students’ attitudes and teachers’ grading practices, due to the high stakes, consequences and pressure.

“We have to find a way to shift the mindset so that errors are seen as information,” Maisel said. “You raising your hand in a class and answering incorrectly should be celebrated because that misconception is likely helping other students. And if all the students only hear correct answers, they A, don’t understand why they don’t understand and B, don’t want to share their answer if the only thing that they ever see are correct answers.”

Maisel hopes that by encouraging staff towards dispelling the culture of compliance and ultimately teaching students to be independent learners focused on skills, starting at the freshmen level, less students will be incorrectly placed in special education in high school. Gupta also sees the importance in creating an intellectually safe environment that values mistakes for the process of learning and developing a skill.

“Sometimes I hear students think, ‘Oh, I am not smart, this person is smart, they get it so fast,’” Gupta said. “Once they understand the concept of productive struggle, that we all engage in that, it is a natural thing, it’s not a failure if you don’t get something [the] first time. To engage with the material, to make the learning your own is proven [and] research-based and these are the processes of learning. I hope it will remove that feeling, like ‘I’m smart,’ ‘I’m not smart’ — we’re all learners. We go through this pit at our own pace and our own journeys. Ultimately we all come out on the other side.”