“The experience of too many women”

Young women take to Instagram to share their experiences as women and facing the threat of sexual harassment and assault

March 22, 2021

“I decided to share my story…”

The reasons and context behind the posts

“When you go to parties in the future, you’re going to have to make sure [you] never accept a drink from someone else, always make sure it’s in your hand or else you’re going to get drugged and probably assaulted,’” junior Alysa Xu’s parents said to her casually, in what appeared to be simply another routine family conversation in the car.

“Off the top of my head, [that] is the first conversation I had with my parents about this,” Xu said. “What stood out to me about it was that I was so young when I had it, and even though I was so young, all the things that my parents were telling me, I already knew about.”

Xu, who attends Cupertino High School (CHS), was in elementary school at the time of this exchange. On March 18, she posted a 10 slide post detailing some of her daily experiences being a woman, and her reflection on this conversation was the first slide. The Instagram post has received over 1,900 likes and 110 comments from peers at schools including MVHS, Lynbrook High School and Homestead High School acknowledging and thanking her for sharing her experiences.

View this post on Instagram

Initially, Xu chose to post the reflection on her private Instagram account, which has around 30 followers, all of whom are her close friends. Despite being hesitant about posting, she received tremendous support from both her female peers, many of whom said they related to her experiences, and her male peers, who said they were thankful Xu had given them the opportunity to become more informed. She then decided to post on her public account. Xu believes that even if her post can “help one person learn something more and allow them to reflect on how they can be doing better” then the “post is worth it.”

In her post, Xu explained that she didn’t aim to be objective, but rather wanted to use writing as an outlet to air her frustrations and exhaustion surrounding current events like the Atlanta shooting and experiences in a society that she believes constantly resorts to victim-blaming instead of acknowledging the real problem — the perpetrators. She explains that she intended to cover two topics through her post — a reflection on her own experiences as a woman and the precautions she feels obligated to take in her daily life, which she believes many of her female peers can relate to.

Xu’s post was the first in a cascade of posts of other young women from FUHSD schools who were inspired to share their stories on Instagram as well, including junior Saloni Mahajan, who also attends CHS. Mahajan recounted her experiences with overcoming the need for male validation, facing the threat of sexual harassment and an instance where a boy she was talking to repeatedly asked her for nude photos. One factor that motivated Mahajan to post on her public account on March 20 which has 1,050 followers, rather than her private one, was how inspired she was by her friends’ courage.

View this post on Instagram

“I definitely think it’s important to hear about things in our community, because unfortunately, many people are only able to see things straight when it happens to someone they know,” Mahajan said. “And although I don’t think anyone is necessarily obligated to share their story, I do think that it can help other people recognize what to look for.”

Xu was surprised to see the extent of the response to her original post, but felt immensely grateful that she had been able to create a safe space for young women in her community to share their experiences. Many of the posts delved into challenging topics including sexual assault and self harm, and Xu acknowledges that revisiting and posting them publicly was very emotionally taxing for many of those who decided to share and often “upsetting and emotionally draining” to read.

Junior Sooraj Gupta grew increasingly shocked as his Instagram feed was flooded with stories from his peers. The sheer volume of posts shattered any previous notions he’d had about the extent of the issues many women faced, and gave him the opportunity to reconsider former assumptions he and his male peers had made about women exaggerating their experiences.

“As more and more women started to post their experiences, [it] made me think about how many people who haven’t posted must have also gone through the same experiences,” Gupta said. “It’s scary to think how many people, or how many women, have gone through that. The people who are posting [are] really important because they’re taking a big risk — [they] really want other people to know about [their] story.”

“I didn’t read the actual post”

Reposting and performative activism

The influx of posts on Instagram was quickly followed by a flood of Instagram stories sharing those posts as well as infographics and accounts that pointed out how to stop perpetuating victim-blaming and rape culture.

After the tidal wave of positive responses she received, Xu published a second post on her account titled “What can I do to help?” that covered various changes that individuals can make in their language and behavior. Xu encouraged her followers to share her post in the caption, but she did, however, acknowledge how quickly sharing information on social media can become performative.

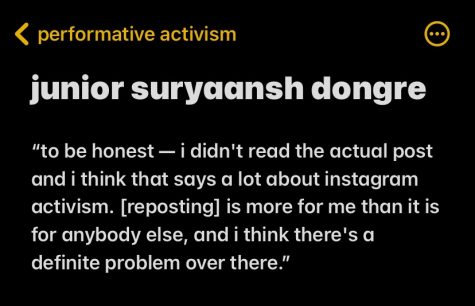

Junior Suryaansh Dongre, for example, decided to take to his Instagram story to amplify the voices of his peers. But upon further reflection, Dongre echoed Xu’s sentiment that, for many people who share posts blindly, their motivation for clicking “repost” may have less to do with highlighting others’ experiences and more with a sense of obligation.

“This is probably very shallow, but the only reason I chose this post was because a lot of people had already reposted it,” Dongre said. To be honest — I didn’t read the actual post and I think that says a lot about Instagram activism. I doubt many people have read the actual [message I wrote] and an even smaller percentage will take [the information] and do something with it. As a man who conforms to the standards of masculinity, I would like to make a change through these posts but, the reality is, I’m probably not doing anything. [Reposting] is more for me than it is for anybody else, and I think there’s a definite problem over there.”

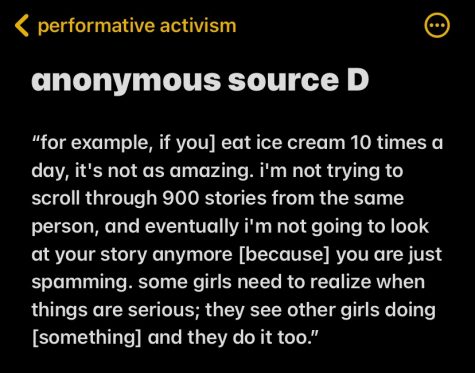

The trend of engaging in performative activism, specifically of blindly reposting tips on how men should change their behavior, is not reserved to people who are simply afraid to be called out. One source — a cisgender, heterosexual male who chose to remain anonymous after seeing a peer who expressed similar views encounter death threats online and feared the same retribution and who we will refer to as D — explains that both his male and female peers will often saturate their accounts with performative content before getting educated, which can have adverse consequences.

“I [have] talked to certain girls about [sexual harassment], and they have no idea what they’re actually talking about,” D said. “They just seem to blab gibberish [and] I also see 900 new posts every day of [them] spamming their main story [which loses] its purpose. It’s taking away from its value when you repost a bunch of random stuff without knowing what you’re actually reposting. [For example, if you] eat ice cream 10 times a day, it’s not as amazing. I’m not trying to scroll through 900 stories from the same person, and eventually I’m not going to look at your story anymore [because] you are just spamming. Some girls need to realize when things are serious; they see other girls doing [something] and they do it too. It’s not just a girl thing, for example, if it’s a guy’s topic [such as football], and a bunch of guys are reposting it, half the people that repost don’t even watch football.”

Mahajan, in contrast to D’s point, says that individuals who appear to be overwhelming their stories with posts are often simply trying to provide resources to individuals looking to change their behavior. She explains that the best way to avoid performative activism is to put effort into getting educated about the issue at hand.

“If you are reposting stories and then not doing anything in your own life to change [your actions], then it’s not effective at all,” Mahajan said. “Social media activism is the first step to gaining awareness for these things. But after that, it’s up to people, individual people to research, ask questions [and] be generally aware of what they’re saying and what they’re doing and how their actions hurt other people.”

Social media does, in many cases, create a platform where engaging in performative activism is easy, according to Dongre. Yet, Mahajan also asserts that social media is one of the most effective tools activists in her generation can employ to spread awareness and possible call to actions, as well as speak up about issues they’ve faced. Gupta echoes this belief, stating how his peers’ posts were crucial to expanding his understanding of the challenges they’d faced.

“[Social media] is really effective because a lot of my friends — guy friends — didn’t really support it or they kept making jokes about it,” Gupta said. “As more people posted things about sexual assault or harassment, the more my friends were like, ‘This is a real issue and it’s not just a simple thing,’ or ‘It’s not just a joke.’ I think it’s really effective, and everyone should at least be [participating by] posting stuff on social media if they can.”

Along with spreading awareness, Xu explains that social media, at its core, remains a platform to connect individuals. From the people who reached out to her personally to thank her for articulating their experiences in her post to those who have shared their stories in tandem with hers, Xu believes that social media plays a crucial role in bringing issues that affect a community to the forefront of their attention.

“I think for this [topic] specifically, I’ve had people reach out to me and say things like ‘I think this is very helpful because it allows people to realize that these aren’t selective cases, these are things that happen to everyone,’” Xu said. “By seeing these things from people in your own community, I think it’s a wake up call to see that these things are very real.

“She did everything right”

Response to current events

One incident that served as a catalyst for Xu’s post was the recent shooting in Atlanta, where eight individuals — seven of them women, and six of them Asian — were killed at three spas by a 21-year-old white gunman who claimed to be absolving his sexual addiction. The incident occured in the midst of a tremendous rise in the number of Asian hate crimes, according to the AAPI, and serves to highlight the dangers that accompany the sexual fetishization of Asian women, according to Xu.

“I just wanted to shut down,” Xu said about her initial reaction to the incident. “I did not want to read more in depth about it because I [knew] how emotionally draining it would be to read through all of this. The media has been covering it and saying like, ‘Oh, like he was just having a bad day,’ and that is somehow a valid excuse to go out and shoot and kill people. This is a hate crime, that is not at all valid. [It] has been very upsetting for me as well as the other Asian American women throughout the country to see the media label it as this. I’m thankful that my grandparents are [with us] right now because I know many people [are] very worried for their elders.”

Another event that charged the undertones of victim-blaming and has remained at the forefront of both Xu and Mahajan’s minds is the abduction and subsequent murder of Sarah Everard, a 33-year-old marketing executive who was murdered by a police officer on March 3 in London. According to the Wall Street Journal, Everard, who was walking home from a friends’ home, chose “well lit streets, spoke with her boyfriend by phone and did many of the things women are advised to do to improve their safety” but still “did not make it home.”

“It was extremely sad, because the thing is, [Everard] did everything right,” Mahajan said. “Every time your parents tell you [to] cover up, make sure you’re not walking for too long alone at night, make sure you’re safe — she did all of those things. And she was still killed. I think it’s really important to notice that because it’s not about telling women what to do, right? Because at the end of the day, what you wear doesn’t end up really mattering. There’s literally little kids that get assaulted in this way, when obviously, they’re not wearing anything to make them look more sexy. I think it’s really important to highlight the fact that we should be focusing on the issue [that] mainly men are doing these actions as opposed to trying to make the women perform actions that will protect themselves.”

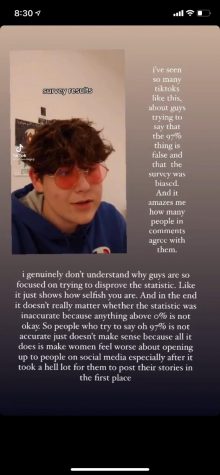

Many individuals who were frustrated by the unrepentant rhetoric surrounding the safety precautions women should take and the concurrent lack of conversation about measures men can take to improve the safety of the women around them took to TikTok to express those views. The rise in content about Everard and educating men about issues that women face was accompanied by the trending hashtag #97percent, which arose from a recent report published by the All-Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) that postulates 97% of women have experienced some degree of sexual harassment.

While the trend was embraced by many who used the hashtag to recount their personal experiences with sexual harassment, assualt or ways in which men could support women, it also received backlash from individuals who believed the survey and subsequent statistic was flawed. While Xu is glad that the trend gave certain individuals the platform to tell their stories, she believes that the experience of women regarding the threat of harassment or assault is not a quantifiable entity.

“I honestly think that we shouldn’t need a statistic in order for our experiences to be validated,” Xu said. “I’m a little upset that the argument has digressed to 97%. Even if it’s not 97%, even if it’s like a much smaller statistic, it should still matter. This 97% should not be the reason that people are like we actually need to start changing because it’s such a huge number, like, no, even if one woman is feeling unsafe, you should do something about it.”

Gupta explains that he belonged to the group of individuals who were initially skeptical about the accuracy of a number as high as 97%, but after seeing the sheer volume of posts like Xu’s, he is “starting to believe it more.” In contrast, Dongre had heard about a similar statistic during freshman year — he remembers learning about it during sex education in Biology class — but was compelled to create change only after seeing the influx of posts.

“With the recent resurgence of [these] brave women sharing their stories, I [am] realizing how pervasive this problem is,” Dongre said. “[It] was really eye opening and terrifying because I’ve shoved that statistic away for so long [by] thinking, I’m not part of the problem because I’m bisexual, I’m not part of this problem because I like men. Just coming up with all these different excuses to distance myself from this statistic and realizing that I’m still a guy, I still conform to those societal standards of masculinity, however small and having that presented again is definitely really terrifying because I’m part of the problem.”

“#notallmen but all women”

Reflecting on the hashtag and the responsibility of men

The insurgence of social media movements that empower women has often been met with the rival hashtag #notallmen, which serves as a bastion for individuals who believe that using the world “men” interchangeably with “rapists” serves to attack all men rather than spread awareness about the issues like sexual harassment or assault. D, who is an advocate for the hashtag, explains how seeing “men” used as a blanket term to describe individuals who harass, assault or rape women deters him from advocacy.

“It is mostly men, but a bigger statistic is that most men aren’t rapists,” D said. “I’m saying, ‘97% of rapists are men, but most of the men are not rapists in the world.’ If I’m scrolling through Instagram one day and I see a story about rape and I’m like, ‘Sh*t rape’s f-cked up, this is bad, this shouldn’t be happening in the world,’ but then I just keep scrolling down and keep reading it and then I see another something that says, ‘Men are so f-cked up, men are so like messed up, I’m so scared of men,’ I see that and then — I’m a man. I’m not a rapist, I’m a man and I feel like, obviously, even though their intention is not to attack me, I still feel attacked, and I don’t want to repost that story anymore and spread awareness with that person’s story because it’s like attacking all men in a way. ‘Men’ is a plural word — it’s not ‘man,’ it’s not a person’s name, it’s not someone specific. ‘Men’ is large, it’s a very large thing.”

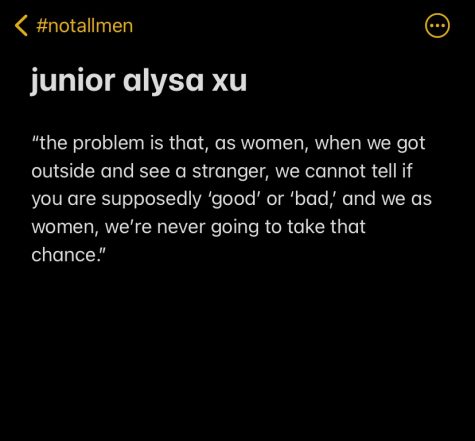

Xu, however, believes that using #notallmen serves more as an avenue for men to disassociate from issues women are expressing and not confront the issue since they are not perpetrators of it themselves.

“#Notallmen because we’re not saying ‘all men,’” Xu said. “The problem is that, as women, when we go outside and see a stranger, we cannot tell if you are supposedly ‘good’ or ‘bad,’ and we as women, we’re never going to take that chance. I’ve had male friends reach out to me, and acknowledge that and they told me, ‘Hey I realized that to a stranger on the street I may be seen as a threat, and that is a problem.’”

Similarly, Gupta believes that the hashtag undermines the value of women sharing their experiences and highlights a more significant issue of refocusing the spotlight on men’s qualms with a movement rather than illuminating those who are attempting to spread awareness.

“When people say not all men their first thought is to defend themselves [when] women speak about their experiences,” Gupta said. “They try to make it about themselves at that point instead of actually thinking about what the woman or the person who was assaulted had to go through. That’s just a really selfish thing to say when somebody else went through something, and especially thinking that, ‘Oh, being accused of sexual assault or harassment is worse than actually being sexually assaulted.’”

D, however, persists in his belief that using “men” as a blanket term to describe all individuals who commit crimes of a sexual nature against women causes more harm than it does good. He explains that when he sees posts that encourage women to “keep their guard up” around men, he feels offended because women have “nothing to fear from him.”

“Women feel like the men around them could be rapists, [but] men feel like the girls around them think that we are rapists, or could possibly be rapists — it’s a trust thing,” D said. “Obviously, if we just get rid of rape, none of this would be a problem. It’s not as serious as women speaking out and using their voice, but it’s still something. Certain people [are] saying, ‘Men don’t speak out, men don’t show awareness,’ and, it’s because of what I’m saying. It’s not that we think that you’re wrong. It’s not like we don’t want to support you. If people didn’t use the term ‘men,’ a lot more men would support it.”

Mahajan explains that the movement is not categorizing anyone or attempting to individualize men, but is instead trying to raise awareness on the issues women have to face in their daily lives. She emphasizes the importance of reflecting on why men who feel compelled to use the hashtag get defensive in the first place.

View this post on Instagram

“At its core, yes, not all men are rapists,” Mahajan said. “Not all men sexually assault people. But if you are [supporting #notallmen], I feel like you need to be reconsidering why you’re so defensive. If you know that it’s not all men, you should be able to have enough connection, self awareness [and] critical thinking to realize that, maybe you’re not [a] part of ‘all men.’ If you’re in the street in the middle of the night, and there’s a man walking across the street to you, are you really going to be like, ‘Huh, he might not be a part of all men,’ like no, I’m going to go to the other side of the street because it’s a scary big man who is probably going to overpower me if he actually was part of those men. I think it’s really important for people to realize that it’s not supposed to be a personal attack.”

D explains that the blanket term “men” can also cause men to feel as if they are not supported by the female community, which creates a barrier in terms of their involvement in the issue.

“If you have support, you feel stronger, you tend to be more outgoing [and] women support each other,” D said. “Even though they are getting raped, and it’s a horrible thing, women support each other in this one topic, and they’re very loud, their voices, they’re very loud. And in the process, if they just said ‘rapists’ instead of ‘men,’ men would join them and help them more than they already do. Right now, people try their best, but I’m saying the man’s voice would also be loud.”

Dongre, in contrast, does believe that to a certain extent, issues around the prevalence of the threat of sexual harassment does actually encompass all men. He believes that all men have a responsibility to educate themselves about the issues that women face and acknowledge that they are a part of the problem because “all men receive the benefits of male privilege and the benefits of sexism in society.” He believes that men should “be able to use [their] privilege in a workplace, or a discussion or just in general spaces where people are sharing ideas, and open up ways for women to speak and share their ideas.”

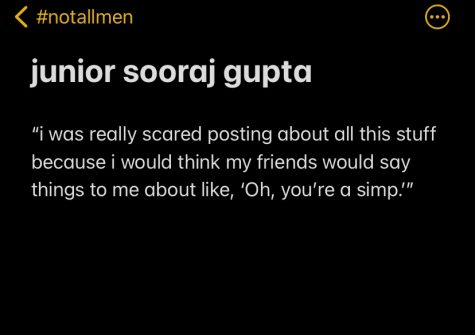

Mahajan understands that for many men, getting involved with women’s issues is often accompanied by severe backlash from peers, which is why many refrain from doing so. She explains that traditional definitions of masculinity foster the belief that men are “not supposed to be super emotional” or spread awareness about issues like harassment and assault because “it makes them a p-ssy” and cause them to be “shunned by their friends,” which is why it is often easier to stay silent — a view echoed by Gupta.

“I was really scared posting about all this stuff because I would think my friends would say things to me about like, ‘Oh, you’re simp,’’” Gupta said, referring to a term used to describe men who are seen as “too attentive and submissive to women.” “That was my biggest fear and that’s what a lot of other guys fear is when posting about this stuff. That’s why I don’t see a lot of guys posting about it, because I think they’re just scared about what their friends think [over] anything else.”

Xu realizes how unresponsive and even destructive male friend groups can be concerning advocating for women’s issues. She emphasizes the importance of men having “uncomfortable” conversations with their predominantly male friend groups in order to destigmatize male support of issues that predominantly affect women.

D also believes that men have a responsibility to spread awareness, but explains that when he feels ostracized, he is “demotivated’ to do so. He explains that men do care and that in his conversations with female friends, has attempted to express this sentiment and stress that, when women bring up people who harass or assault them, he is “not like that.”

“When you demotivate me, when you attack me, I tend to not want to support you anymore, even though I know I need to,” D said. “I’ll still support you but not with 100% energy, but when I see people say not all men, then I get a little energy. The women are inclusive of the men that are trying to help them. When [women] say, we have to protect ourselves from men, I feel like [they are] trying to protect [themselves] from me and [I] don’t feel like I’m a part of the movement.”

Overall, Mahajan feels frustrated that men are using #notallmen as an excuse not to associate with a movement that profoundly impacts the lives of so many women. She cites how men will often bring up the issue of women who falsely accuse men of harassment — an occurrence so infrequent that it bears no comparison to the magnitude of women who feel unsafe.

“Although yes, it’s not all men, I think that that’s really not the biggest problem you could possibly have with this,” Mahajan said. “You still have the privilege and honestly, you can deal with being called ‘all men’ when everyone knows it’s not actually all men. You can deal with that for a little bit if everyone else has to deal with all this.”

“It made me so uncomfortable”

Personal stories and moving forward

In her post on Instagram, Mahajan reflected on an experience she had with a boy she’d been talking to who would relentlessly ask her to send him nude photos of herself, despite her insistent refusal, and explains that such requests made her immensely uncomfortable. At the time, Mahajan believed the encounter was normal, a notion she has only recently realized was incorrect.

“I didn’t understand why it made me so uncomfortable,” Mahajan said. “I thought that this was a normal thing that teenage boys did, which I was wrong, but there was no way for me to know I was wrong. I was [asking] myself, ‘Why am I being such a prude?’ Eventually [his requests] just kept escalating and I decided that I wasn’t comfortable and broke it off. I was a little embarrassed that I had engaged this man for so long and not really done anything forceful about it [or] that I hadn’t done more.

Mahajan explains that her misconceptions about the normalcy of that boy’s behaviors reflects a larger problem about women’s safety and sexual desires to be ignored or not taken seriously. As a result, she explains, women tend to have to embed certain precautionary measures into their daily lives—most of which, like in the case of Everard, don’t end up being of much assistance in encounters with dangerous individuals anyway. Xu echoes this sentiment, recounting how she constantly checks if people are following her and always keeps her phone in her hand when walking somewhere.

For Gupta, these posts have helped dismantle the idea that he and his friends had about women who spoke up about the threat or their experiences with harassment or assault. Mahajan also cites a similar mentality among her male peers, stating how such accusations are usually baseless and do not make sense in the larger context of potential consequences — or lack thereof — that victims and perpetrators will face.

Overall, Xu reflects on how a large part of her motivation to post was to combat the constant criticism that women who choose to speak up feel. She wanted to give a voice to the struggles that she and so many fellow women face each day, and she feels empowered that as a result, so many young women found their voice to do the same.

“I think that a lot of times women will be labeled as too aggressive [or] too assertive, or they’ll be seen as like, ‘Oh, you’re just overreacting. You’re being too sensitive,’” Xu said. “On a lot of these posts that I’ve seen from my peers, they have explicitly stated, ‘I’m not doing this for attention. I’m not asking for pity. I’m not asking for empathy. I just want people in our community to see what’s happening.’ I think that exemplifies the issue of the fact that we even have to explicitly state, ‘I’m not doing this for attention,’ [it] kind of shows that like people are so quick to point fingers and invalidate our experiences.”

Resources

Books, videos, articles, hotlines and centers to get more educated or seek help

Books:

- Know My Name: A Memoir — Author: Channel Miller

- Boys and Sex:— Author: Peggy Orenstein

- Speak— Author: Laurie Halse Anderson

- Asking for It: The Alarming Rise of Rape Culture–and What We Can Do about It— Author: Kate Harding

- Yes Means Yes!: Visions of Female Sexual Power and a World without Rape — Author: Jacyln Friedman

- Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture — Author: Roxane Gay

- A False Report: A True Story of Rape in America — Author: T. Christian Miller & Ken Armstrong

- We Believe You: Survivors of Campus Sexual Assault Speak Out — Author: Annie E. Clark & Andrea L. Pino

- Dear Sister: Letters From Survivors of Sexual Violence — Author: Lisa Factora-Borchers

- I Have the Right To: A High School Survivor’s Story of Sexual Assault, Justice, and Hope — Author: Chessy Prout & Jenn Abelson

- I Know why the Caged Birds Sings — Maya Angelou

- The Purity Myth: How America’s Obsession with Virginity is Hurting Young Women — Jessica Valenti

- Rape Recovery Handbook — Aphrodite Matsakis

- Shout — Laurie Halse Anderson

Videos:

- Sexual Assault and Harassment — Planned Parenthood

- Sexual Harassment Awareness and Prevention — Department of Defense Education Activity

- What is Sexual Harassment? — AMAZE org

- How Do You Know if Somoene Wants to Have Sex with You? — Planned Parenthood

Articles:

- Sexual Harassment Awareness and Prevention — Department of Defense Education Activity

- What is Sexual Consent? — Planned Parenthood

- How do I talk about consent? — Planned Parenthood

- What should I do if I or someone I know was sexually assaulted? — Planned Parenthood

- Sexual Violence — Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Hotlines/Centers:

- RAINN: Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network — HOTLINE NUMBER: 800-656-HOPE(4673)

- ICASA: Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault (rape crisis centers) — https://icasa.org/

- NSVRC: National Sexual Violence Resource Center — https://www.nsvrc.org/

- SAFER: empowers student movements to combat sexual violence on college campuses — https://safercampus.squarespace.com/

- Prevent Connection — http://www.preventconnect.org

- Office on Women’s Health— https://www.womenshealth.gov/relationships-and-safety HOTLINE NUMBER: 1-800-994-9662, 9 a.m. — 6 p.m. ET, Monday — Friday