WASC Goals

MVHS works to implement goals and feedback following WASC accreditation visit

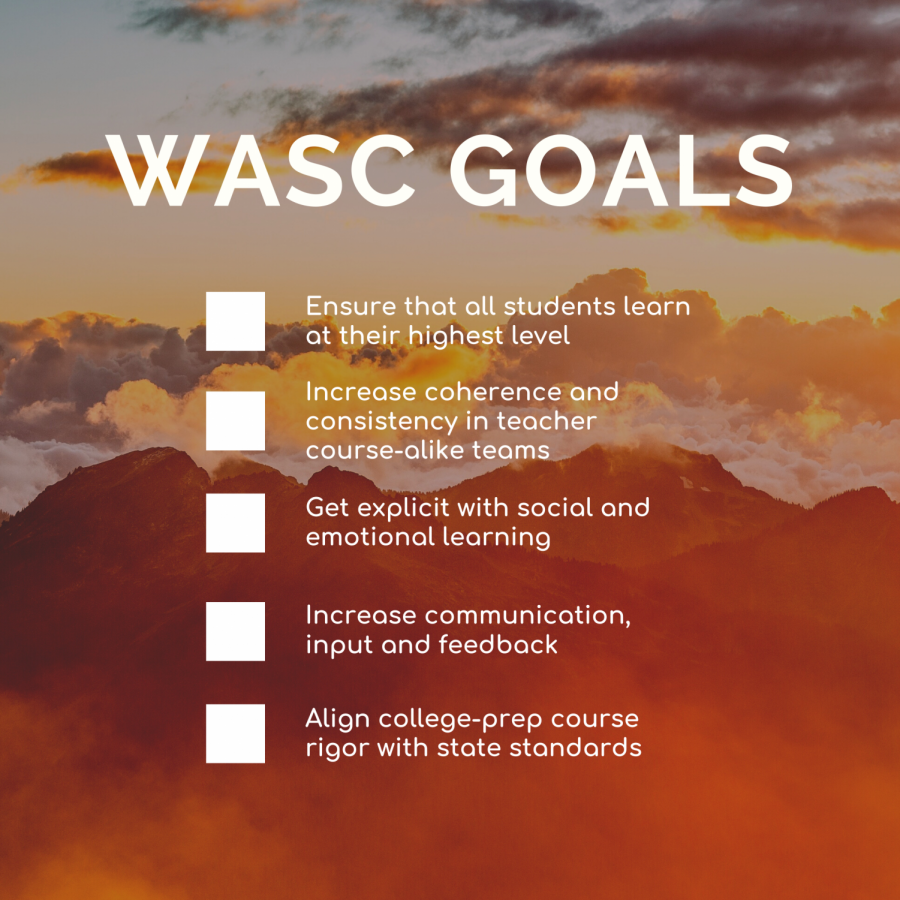

The visiting committee suggested a fifth goal in addition to MVHS’s four original goals.

December 17, 2020

In early November, officials from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) audited MVHS online classes in lieu of their in-person visit that was canceled last March due to COVID-19. The visitors provided feedback on MVHS’s self-report, culminating the school’s latest six-year-long WASC accreditation cycle, which ensures that MVHS diplomas are valid.

Math teacher Sushma Bana, who led MVHS’s WASC team, characterizes the accreditation process as a “self-study” that the school must undertake. Bana says that a key challenge in a process so extensive and thorough was ensuring that the perspectives of all stakeholders were considered. To that end, the WASC team divided itself into five focus groups: school organization, curriculum, instruction, assessments and school culture. Each group sought diverse viewpoints as they considered MVHS’s strengths and weaknesses, distilling their findings into four central goals presented in the final WASC report.

“[The process] has to involve all stakeholders — students, teachers, administration, classified staff [and] parents,” Bana said. “The whole community has to come together and identify what are the needs of the school, what are the big areas that our school is doing well on, what are some of our future needs and what we should do as a school community to address those needs.”

That core mission — ensuring that all voices are heard — was also echoed within the final report itself. Goal 4, for example, is about setting up feedback streams to increase communication among students, parents, staff and school administrators. And Goal 1 focuses partially on ensuring that all students receive support to learn at their highest level, especially students who, according to Bana, “fall through the cracks” unnoticed amid MVHS’s high test score and academic averages.

Following the virtual visit, WASC visiting team members shared their feedback on MVHS’s goals in a group dialogue. According to English teacher Hannah Gould, the visitors praised MVHS for not only its strong academics but also how the school maintained these academics in spite of distance learning’s limitations.

“One of the visiting committee members [who] has a Ph.D. in online education said that what we’re doing for remote learning is basically comparable to a real, accredited online academy,” Gould said. “Actual pandemic remote emergency learning isn’t really supposed to be at that high standard, but we’re just doing it.”

Visiting team member Michael Casper, an assistant principal of San Marin High School in Novato, believes one of the most valuable positives he took from the virtual visit was the manner in which various MVHS administrators and faculty cared for students through day-to-day interactions. Because of this, he says that the visit was also a valuable opportunity for him as an administrator.

“[There is] a very caring group of adults at [MVHS],” Casper said. “Being on a WASC visiting team, I’ve been on both sides of it. And there’s no better form of professional development for an educator than being on a visiting committee.”

Gould is proud that the school’s recent efforts in advancing social emotional education was recognized.

“[Social-emotional care is] something that we’ve been really berating ourselves about four years now and being like, ‘Oh, we don’t care enough; we need to get better at this,’” Gould said. “So the fact that they noticed that as a positive was validating. Obviously, we have a lot more work to do, but it felt really good that [our efforts] were apparent.”

The WASC team also offered critical feedback, especially concerning inclusivity and accessibility. For example, the visiting team suggested adding an additional fifth goal for MVHS teachers to reduce the rigor of college-prep courses, such as lowering grading standards and removing additional skills and assessments that go beyond California’s educational standards.

Bana says that this will mend the potential holes that are created when certain students sign up for what are supposedly MVHS’s least rigorous courses but still find those courses to be inaccessible because of their rigor. But the difficulty is also double-sided, because rigor is a systemic feature of MVHS.

“If we push that back to the teachers, that, ‘Hey, you have to teach courses at a lower level,’ then there may be confusion because at [MVHS], we have this history of not teaching to the state standards,” Bana said. “I can say for myself that I know what the state standards are but I don’t look at them every day to see what I’m supposed to teach.”

Gould agrees, believing that among the WASC goals, reducing rigor will be the most complicated to put into practice.

“Because [of] the legal protections that teachers have over the content and grading practices of their classrooms, it’s one of those things that can’t just be an executive order, like ‘Everyone needs to reduce the rigor by 15%,’” Gould said. “It’s going to be a long process of conversations and resistance and work in groups and slow, gradual development over time.”

MVHS has already started to implement certain facets of its WASC goals. This year, MVHS began working towards Goal 3 by forming a Social-Emotional Learning Task Force and rolling out Advisory lessons that emphasize topics like combatting stress and negativity. In the coming years, the staff and its various task forces will continue to explore avenues to implement their goals to make improvements.

“WASC … never stops — it’s an infinite report that’s always growing, always evolving, and you’re never like finished,” Casper said. “Think about just the last 10 years — how schools have gone more student-interest-based. Even if you take COVID-19 away, a lot of things are different than they were just the last time WASC came to MVHS.”