Live action ‘Mulan’ is visually stunning and historically accurate, but lacks charm and focus

A fair stab at retelling the historical legend, but fails to meet expectations on-screen and sufficient Asian representation off-screen

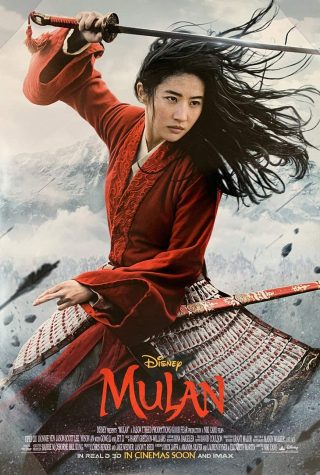

An offical movie poster for the Disney live-action version of “Mulan.”

September 25, 2020

On Sept. 4, the live-action movie adaptation of Disney’s 1998 “Mulan” was released to the public through Disney’s streaming platform, Disney+. Those who subscribe to the streaming station could purchase the film for $30. While it is unclear how much the movie has made so far, “Mulan” has claimed the top spot at box offices in the United Arab Emirates and Malaysia, and had the best opening weekend of 2020 in Singapore and Thailand.

The cast is composed of star-studded, A-List Chinese celebrities, aimed to both meet the public’s cry to have authentic cultural representation as well as help attract Chinese audiences to the theater. Unlike other Disney live-actions that are almost exact replicas of their animated versions, such as “Cinderella” and “The Lion King,” “Mulan” follows a much different plotline from the original animation, shifting characters and changing locations.

The live-action “Mulan” takes place during the Northern Wei Dynasty in 4th to 6th century AD ,although not all costume or set design is historically accurate to this time period. In the film, men are considered to be the superior gender and women are expected to bring honor to their family through marriage. The film follows Hua Mulan, played by Liu Yifei, through her decision to disguise herself as a male and take her father’s place in the Imperial Army. She must learn to strengthen her inner chi (energy), become a courageous fighter and protect her country against Bori Khan, played by Jason Scott Lee, a leader of northern Mongolian invaders who wish to dethrone the Chinese emperor. Bori Khan is assisted by Xian Lang, played by Gong Li, a female witch with shapeshifting powers who is ostracized from society.

Watching “Mulan” was somewhat of an indescribable experience. I got to see my favorite childhood animation and female protagonist recreated in a live-action. I finally saw characters who looked like me, my family and my relatives on the “big screen.” I even related to Mulan’s family at the beginning of the movie — they had a family of four with two girls, just like me. Mulan was the older sister, just like me. Mulan was Chinese and female, just like me. These were feelings I never had the opportunity to experience prior to “Mulan,” and I finally felt like I was being seen and heard by popular media.

However, while the movie has many positives, such as its focus on historical accuracy and beautiful cinematography and scenery, overall, it fell flat in many of its most important aspects, such as plot, humor, secondary characters, and theme. The movie itself seemed to be confused as to what direction it was going in and the unnecessary addition of storyline points such as magical chi drew focus away from the message of the original Ballad of Mulan. Mulan promised to bring us fair representation of its Chinese characters, yet miserably failed in meeting the same standards off-screen, appointing white people in some of the most important creative positions in film production (director, writers, costume designer, and set designer).

Starting with the positives, Disney’s attempt at portraying Chinese culture greatly improved from the original 1998 film. While the basic premise of the animated version is the same, Disney updated many important details that make the live-action more historically accurate and true to the original Ballad of Mulan. This included renaming the Huns to the Rourans and changing the location of the attack at the beginning of the film from the Great Wall to the Silk Road. Mulan’s family name has been changed from Fa to Hua since her name in the original ballad is Hua Mulan. These minor changes show how Disney has taken steps to more accurately portray POC stories, a move that should be applauded and normalized in the film industry.

To market to Chinese audiences, Mushu, the talking dragon, was removed from the live-action, as he was deemed disrespectful towards Chinese culture. In his place, a phoenix appears from time to time, providing help and guidance to lead Mulan in the right direction. To acknowledge the #MeToo movement, Li Shang, Mulan’s commanding officer and love interest in the original film, is noticeably absent from the live-action. Instead, his role has been divided into two different characters: Commander Tung, played by Donnie Yen, a high ranking leader in the Imperial Army, and Honghui, played by Yoson An, a fellow army recruit and Mulan’s potential love interest. Although Mushu and Li Shang are defining characters who have a major impact on the viewer’s experience, I do appreciate Disney’s more socially-conscious approach to recreating a story that is both culturally accurate and fitting to today’s social climate.

Xian Lang, an entirely new character, takes on the role of “bad guy turned good” and gives another opportunity for the film to push the message of female empowerment, as she refuses to remain a pawn for Bori Khan. Throughout the movie, both Mulan and Xian Lang prove that they can be just as, if not more, powerful than their male counterparts. I loved how the film took the original message of the animation and exemplified it twofold, rejecting the imbalanced gender dynamics of Chinese traditional culture.

Despite the numerous differences between both films, many live-action scenes, such as soldiers’ training sequences and the pivotal avalanche scene, are extremely reminiscent of its correlating scenes in the original animation. These moments are incredibly captivating and nostalgic, making the audience feel like it’s truly a retelling of “Mulan” and not just a completely separate film.

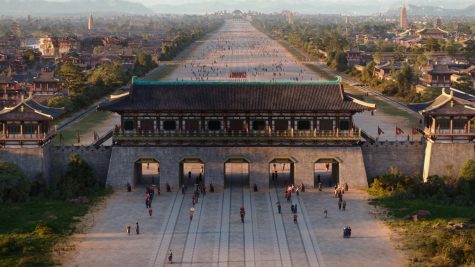

Visually speaking, “Mulan” is a treasure chest of breathtaking natural and architectural sights. Mulan roams endless grassy open fields, ice-capped mountains and a regal, imposing city that houses the emperor’s palace. The scenery brings a realistic attractiveness to the original animation. The costumes and props are incredibly elaborate and detailed, but most importantly, historically accurate and truly encapsulating of China’s rich culture.

Additionally, Liu Yifei, who is skilled in martial arts and sword-fighting, is a near replica of the mighty soldier we envisioned Mulan to be in real life — she is both delicate and strong. Her fierce fighting scenes as well as her entrance during pivotal scenes, such as when she returns to her army after an avalanche, screams female empowerment and literal goddess material.

Although each character was well-cast and the film itself is visually stunning, plot and character-wise, “Mulan” is not nearly as strong. The consequence of adding multiple new characters, the live-action takes away screen time from fleshing out many of its side characters. The villain Bori Khan was given time to show more of his personality and isn’t as one-dimensional as he is in the animation. However, Mulan’s gang of soldiers (Ling, Yao, and Chien Po) are barely given any screen time to make a memorable impact on the audience and not nearly enough to live up to their lovable animated characters. Mulan didn’t have enough bonding interactions with her fellow soldiers to convince me that they would completely disregard the fact she was female to follow her into battle, especially during this time period.

Moreover, the decision to add in the plot point of chi (energy) that made Mulan standout in comparison to her fellow male soldiers was unnecessary and contradictory to the message of the original Ballad of Mulan. This plot point may have worked if they had used it in its definition of being a natural energy in all living entities, but they treated it like a magical superpower that instantly gave Mulan a boost. In the traditional legend, Mulan is an ordinary girl, someone all girls can relate to, who does not possess any sort of magical element that gives her an advantage over others. The original Mulan proves that she can physically match her male peers without any pre-disposed abilities. The introduction of and focus on this chi for the majority of the movie largely undercuts the traditional ballad’s theme and turns the growth of a witty underdog to one of a magical individual with absolutely no shortcomings, who is automatically destined for success.

In addition to the general storyline, the writers’ attempt at humor throughout the film was sometimes spot-on, but at other times, awkward and nowhere near as funny and charming as the animation. The plot felt like it was moving at lightspeed, yet it also felt like nothing was actually happening during the entire movie. Looking back, the film was like a mash of different messages: female empowerment, nationalism, bringing honor to your family, societal conformity, staying true to yourself and embracing your strengths. While I appreciated the focus on the two female characters, Mulan and Xian Lang, the witch added for the live-action, I was also left confused, wondering what the movie’s primary meaning and goal were.

In general, “Mulan” did a fair enough job in giving us a real-life Mulan who was loyal, brave and true. “Mulan” didn’t contain quite as much magic, charm and allure as the original animation but most animations turned live-action suffer the same fate. “Mulan” traded goofy, lovable audience favorites for more muted and serious characters, which in turn, gave the live-action a realistic charm of its own. The animated version is more suitable for younger audiences, while the live-action is for those looking for a more mature take on the Disney classic.

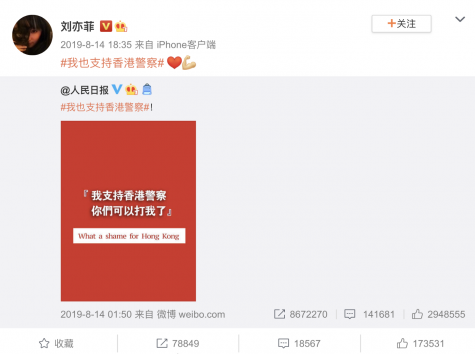

Offscreen, “Mulan” has been embroiled in controversy ever since it was announced, from whitewashing concerns to the removal of popular characters. More recently, Liu Yifei drew criticism for her comments regarding the Hong Kong protests after posting the hashtag #IAlsoSupportTheHongKongPolice on the social media platform Weibo. While many have decided to boycott the movie, it is important to note that the context behind Liu’s post was largely distorted by American media outlets. She had actually reposted an article that included quotes from Fu Gaohao, a reporter who was brutally assaulted by protestors and later rescued by the Hong Kong police, hence Liu’s use of the hashtag supporting the police. Her social media post was taken grossly out of context and in no way is evidence that Liu endorses and supports police brutality in Hong Kong.

In addition, “Mulan” has also come under fire for filming partly in Xinjiang, a region in China where Uighur Muslims have been detained in re-education centers. Disney has long-eyed China’s huge market, and it seemed they weighed profit more heavily than social responsibility in their production of “Mulan.”

Adding on to the film’s long list of controversies, many noticed that the majority of the production staff on “Mulan,” including the director, four scriptwriters, casting director, set designer and even costume designer, are all white. The fact that Disney failed to hire a single Chinese, not even Asian, staff member in at least one of the production’s major creative positions is extremely disappointing. “Mulan” is seemingly a step toward diversity and representation in the film industry, but in reality, it is nothing but performative representation.

While it’s amazing to see Asians represented on screen, it irks me that a majority white production team, even with Chinese advisory input, produced a film telling a story of Chinese history and culture. Although the characters onscreen are Asian, they are simply actors performing the roles crafted and controlled by non-Chinese people behind the camera telling them how to act in a Chinese story; they’re pretty much living, breathing puppets. Even with the significant amount of research and observation the production team claims to have done, an almost all-white production team behind an all-Asian cast doesn’t seem very progressive or diverse at all.

Disregarding the political and social battleground “Mulan” is facing offscreen, it is still a film I recommend everyone to at least give a chance at watching, especially if you were a fan of the original 1989 animation. You can’t deny Liu Yifei did a wonderful job in bringing Mulan into the real world, capturing every bit of the beauty, strength, honor and bravery her animated counterpart possessed. Even the fight sequences are enjoyable on their own, especially when we see Mulan use her wits rather than her strength to save the day, proving the phrase “4 pounds can move 1,000 pounds,” a popular Chinese proverb used often in the movie. At the end of the day, the film is still another step into an era of POC representation in film and media.

While I wanted so badly to love “Mulan” and proclaim it as one of my favorite movies of all time, especially since it is a major milestone for Asian representation in film, I couldn’t ignore many of the film’s major pitfalls in both plot and production. The story lacked too many of its most essential components (storyline, theme, humor, etc.) and for that, the movie doesn’t come anywhere near meeting my expectations. I will always remember “Mulan” as a great step forward for Hollywood and the film industry, but also as a half-step backward for its lack of representation off-screen.