Nordic versus American Education: Finding a balance

Examining what can be learned from the two regions by differentiating their particular takes on the education system

December 13, 2019

magine sitting in a classroom waiting for the school day to end. When the bell rings, your teacher announces to the class that there is no homework. However, this is neither considered a surprise nor a sign of relief because your teacher rarely assigns homework in the first place.

magine sitting in a classroom waiting for the school day to end. When the bell rings, your teacher announces to the class that there is no homework. However, this is neither considered a surprise nor a sign of relief because your teacher rarely assigns homework in the first place.

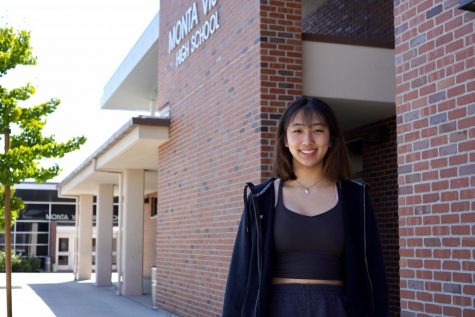

According to sophomore Tristan Skov, students who live in Nordic countries — Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Greenland, the Faroe Islands and Åland Islands — have different routines both during and outside of school because of the differences between American and Nordic education systems.

Skov, who moved from Copenhagen, Denmark to California in fifth grade, notes that school days in Denmark are typically longer than in America. However, students receive little to no homework, which is a significant difference compared to students in the U.S., who are assigned homework more frequently in order to reinforce the material learned in school that day.

“They don’t get homework because the parents are very busy with work,” Skov said. “So if the kids come home with a bunch of homework, the parents would constantly be asked, ‘Oh, I need help with this. I need help with that.’ [The teachers] don’t want that for the parents.”

Asides from this disparity between America and the Nordics, Skov also appreciates how healthcare and education are free for all, despite being funded by taxes. Additionally, he highlights how students are able to create strong bonds. Since most schools have students stay with the same group of peers up until ninth grade, they’re able to form long-lasting friendships. In addition, teachers are expected to build closer connections with their students, which Skov finds makes learning easier, in regards to communication.

Junior Isak Westelius, who moved to the U.S. from Sweden in fourth grade, agrees with Skov and believes that America, in general, should promote a more “progressive” relationship between teachers and students. However, Westelius also notices that Sweden tends to take the expectations of teachers a little overboard.

“People talk to their teachers like they’re friends, call them by their first name and snap them,” Westelius said. “Teachers are expected to be therapists, and they’re so overworked. The expectations for teachers are crazy.”

In America, students have the option of taking the regular or advanced version of a class. However, in the Nordics, there are no advanced courses. Westelius disagrees with this type of education system where all students are at the same level of education because it doesn’t account for the different learning speeds of students.

“Class [in Sweden] was really slow and in second and third grade, I’m pretty sure I learned literally nothing,” Westelius said. “It was just really boring, but when I moved to America, I was way behind in math. We did a review quiz on the first day of school and I was like, ‘What are these things? I’ve never seen that before.’”

On the other hand, Anu Valtanen, who moved from Finland 20 years ago and is a mother of two who both attended MVHS, believes that classes in America provide students with more opportunities to practice public speaking — a skill that is lacking among some students in Finland. She also admires how involved parents are in American schools, whether it be through volunteering or lending a helping hand academically.

Aside from these things, Valtanen thinks that American schools could learn from those in Finland as well, by giving students less homework, as she believes that time as a child should be spent doing what one loves with friends and family. Moreover, she also believes that standardized testing should be eliminated and that in order to ensure that students are actually learning, schools should focus on having students take smaller steps and more focused tests. Valtanen notes that because of the absence of standardized tests in Finland, teachers have more freedom with the curriculum.

“A lot of time is dedicated to preparing the teachers for [teaching] the [material on] standardized tests, and for the teacher to prep the students [afterwards],” Valtanen said. “With no standardized testing, [teachers and students] could focus on things they find more useful or interesting on the subject. People aren’t ranking schools based on standardized testing and it makes the schools less competitive.”

Additionally, Valtanen has noticed that schools across America tend to overlook certain subjects, and at MVHS, STEM-related courses overshadow arts and humanities. She notes that in Finland, schools hold equal importance for all courses, giving students more freedom when it comes to what they want to pursue. Valtanen believes that because students have this sense of independence, test scores are higher and education in Nordic countries are deemed as some of the best.

“[Finland] believes that all the other subjects, like music, art and crafts are just as important as math,” Valtanen said. “I just feel that it’s sad because there’s definitely enough time to learn math in your lifetime. I mostly feel that the pressure in this area comes from the parents. Some don’t appreciate art or music classes so much, and so many kids think that ‘Okay, I can’t take those classes [since they’re] not so important. I just have to focus on math and science.’”

Westelius points out that because all subjects are equally emphasized, students are also able to choose their potential careers both earlier and more comfortably. He believes that in America, not only do students have to focus on school, but extracurriculars as well in order to achieve their goals. Whereas in Sweden, students mainly just focus on what they want to pursue in the future.

“A good thing in Sweden is you get to specialize earlier,” Westelius said. “You get to choose your path when you’re in high school. If you really don’t like to do math, you really don’t have to do that much math.”

Despite feeling that he did not learn a substantial amount during his childhood in Sweden, Westelius notices how in America, learning is not limited to inside the classroom. Similar to Valtanen, Westelius realizes that the difference between these two countries stem from the amount of pressure put on students.

“I feel like people don’t care at all about what they’re learning here,” Westelius said. “They care way more about the grades. If you want to get into a good college in Sweden, the only thing you need is good grades, because that’s the only thing you send. But here, that’s not enough. People want [to] exceed in extracurriculars but also do well academically, so they BS a lot of their work, and I think that’s really toxic.”

While neither America nor the Nordic countries are perfect when it comes to education, Westelius and Skov agree that finding a balance between academics and health with personal interests is something both regions can improve on. While the Nordic countries focus on freedom for the students, sometimes the regulations are too loose. Skov recalls his visit to Denmark over the summer, during which he attended a school there for two days. He noticed that the students did not use class time efficiently.

“I saw that they had so much free time and that they don’t work, so maybe giving [the students] some work [would be] good,” Skov said. “Learning to balance out between education and free time [is really important]. Over here, I tend to see that students don’t have any free time. They might be more depressed or all the work gets in their heads because they have so many things to do. Balancing it out and [knowing] what the limit is will help [students learn and experience new things].”