Hooked online: how social media affects cognition

Analyzing the pervasive nature of social media in students’ lives

September 28, 2018

Pramodh Srihari had always been a bright student, scoring at the top of his class. Then, he got his first phone, changing his orderly schedule. From then on, Srihari’s time was swallowed by his addictive pastime. It started with endless games — Clash of Clans and Clash Royale, then Instagram and other social media. His phone disturbed his daily routine, consuming his mind to the point where academics were his second priority.

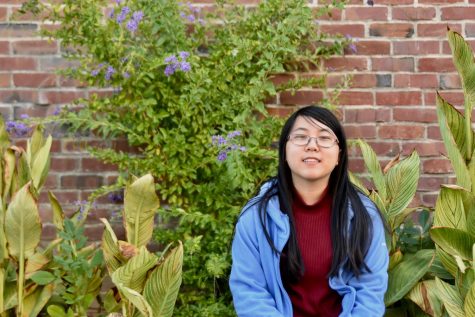

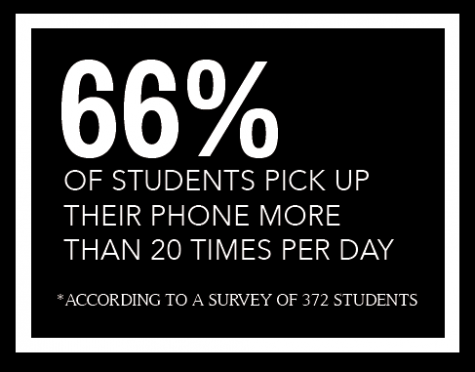

Social media has a large impact on American society. On average, Americans check their phones 80 times a day or every 12 minutes. According to a study of 2,000 people by the technology company Asurion, the longest the average person can go without their phone is four hours. Sophomore Lydia Lu can easily relate to this idea, claiming she picks up her phone over 25 times a day, curious to find out what is happening in her friends’ lives.

“[Social media] has definitely changed my life, because I use it a lot now,” Lu said. “I can’t imagine before when I didn’t have it.”

Similarly, Srihari finds himself pulling out his phone between classes to scroll through Instagram, even though there may be nothing new to look at. He thinks he spends an hour every day scrolling through social media.

But Lu and Srihari, according to the Asurion study, probably pick up their phones much more often than they think they do.

How social media changes the brain

The real culprit for absentmindedly checking one’s phone is serotonin. According to Verywell Mind, an online resource that provides guidance on how to improve mental health and find balance, social media use increases the production of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that often is referred to as the “happy” chemical. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin are chemical messengers that carry and balance signals between neurons and other nerve cells in the body. They can affect both physical and psychological factors including mood and heart rate.

Serotonin is crucial to the body’s function. According to Medical News Today, serotonin deficiency can cause depression, while excess serotonin can cause agitation and increase in heart rate. Serotonin is linked to these symptoms since it regulates the dopaminergic system which plays a part in behavioral actions. When the dopaminergic system is limited by serotonin, it becomes hyperactive, increasing aggressive impulses.

However, serotonin is not the only neurotransmitter that plays a role in social media addiction — dopamine has a hand in this issue as well. The driving force behind many of the brain’s functions, dopamine creates a pleasurable high when desired actions are performed. Dopamine, directly involved with movement, memory, reinforcement and reward, causes people to constantly check their phones to satiate their desire for technology.

While both neurotransmitters correlate with how a person experiences pleasure, serotonin affects mood, whereas dopamine is related to reward-motivated behavior.

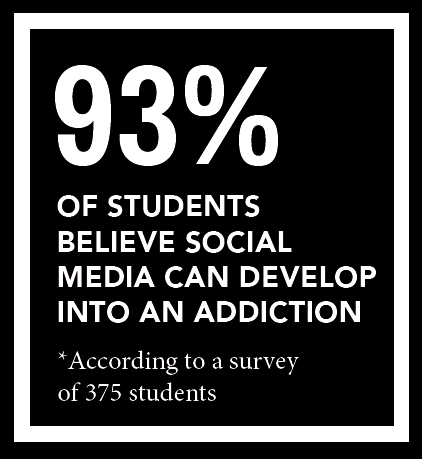

The psychology of the current generation’s interaction with social media is coming to the forefront of the discussion about its lasting impact on humanity.

The start of an addiction

Social media can become addictive because it activates specific neurotransmitters like dopamine. Dopamine is notable for being in charge of reward-based behavior; however, it would be more accurate to call it a mediator between desire and motivation.

Dopamine is released naturally based upon feelings of pleasure but can also be activated via stimulants, such as certain medications, types of food or music. That being said, a constant release of dopamine can become addictive and result in an increase of impulsive behavior.

According to senior Pranav Shenoy, the addictive nature of social media affects many people. He thinks that status updates and getting likes or followers are a form of short-term pleasure.

“On a small scale, that’s fine, but to devote your life to short-term pleasures is not really a good thing,” Shenoy said. “Either they are not used to getting pleasures regularly, so therefore they look forward to these things, or they simply do not want to work toward long-term pleasures, and instead strive for short-term pleasures.”

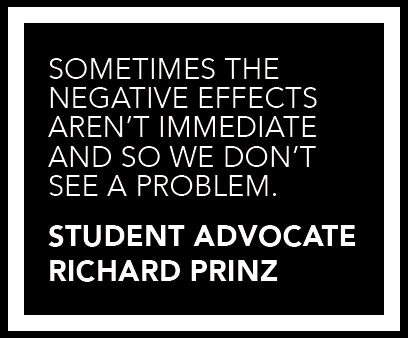

When people receive likes on a post or gain followers, dopamine in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the brain is activated, resulting in feelings of reward. Student advocate Richard Prinz has worked with students who have become addicted to social media or other types of technology.

“The thing with addictions is you do it a little bit and then you want more, so you start doing it more and more and then it’s on your mind a lot like, ‘Oh, I want to go do it. I want to do that.’ So then it becomes even more difficult to stop it or change it,” Prinz said. “Sometimes the negative effects aren’t immediate and so we don’t see a problem.”

Prinz believes that frequent usage of technology can also correlate to the formation of an addiction.

“It depends on how it’s being used and how often, because people get addicted,” Prinz said. “This morning I was hearing about somebody’s brother who’s in eighth grade who’s addicted to a video game. He’s very much like, this is his life, this what he wants to do all the time. That’s usually part of the definition of a disorder when it starts to interfere with your functioning, your work or your school work.”

With the rise of social media in modern society, specialists like MVHS psychologist Sheila Altmann have taken attempts to counteract what she labels media platforms’ harmful effects.

“If it is at a level where, say, we as professionals feel that is unhealthy, we would encourage parents to do something to actually limit it,” Altmann said. “But again, when you limit [social media], you have to realize you have to have something to replace it with. If that’s a person’s only source of entertainment, then when you take it away they may just fall into a deeper depression.”

Maslow’s hierarchy and sense of belonging

Altmann believes that increased teenage reliance on social media can be explained by Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

“On Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, sense of belonging is one of the biggest needs, and belonging might be synonymous with affirmation,” Altmann said. “If you’re accepted, that’s a sense of belonging, and we may be reaching out further and further to get that kind of affirmation.”

Altmann also believes this need to belong is prevalent in teenagers, and she says Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stages can be used to explain this idea. According to Erikson, teenagers are in the stage of “Identity and Role Confusion” and are constantly trying to fit into their society in hopes of proving their identity as worthy to those around them.

Social media becomes an ubiquitous source for affirmation and belonging, having multiple apps that share a similar system of likes and followers. Altmann thinks the reason why social media has become so important in this development of belonging and need for affirmation is because it computes senses of belonging into measurable numbers.

Yet, Lu maintains that getting likes and gaining followers on social media does not affect her personally.

“I know that with a lot of people, they compare themselves to how many followers they have compared to this person, or how many likes [they have],” Lu said. “I know it causes self-esteem issues, but for me it doesn’t really affect me. Generally I’m not really sad when I don’t get a lot of likes on this picture, because it doesn’t really matter.”

Although it may not impact her personally, Lu reflects the same sentiment that Altmann shared: people are getting affirmation and a sense of belonging from social media. Srihari, however, does not share this sentiment.

“I think I don’t really notice [likes and followers] because I don’t post a lot, but when I do, it’s kind of annoying to see all the notifications,” Srihari said. “I think I disabled comment notifications. It’s nice [to see likes] but it doesn’t help you in any way. I realized that. Why do you want to look at that?”

Srihari and Lu both see the volatility of social media and how it can be beneficial and detrimental. Balancing this double-edged sword is something that needs to be sought after by everyone, according to Prinz.

“Social media is like a shovel. You can dig holes and you can plant things and grow things,” Prinz said. “You can use the tool constructively or you can take the shovel and hit somebody over the head with it, [and it becomes] a weapon and [is] harmful.”