A familiar space

International students explore how they found their place at MVHS

May 25, 2018

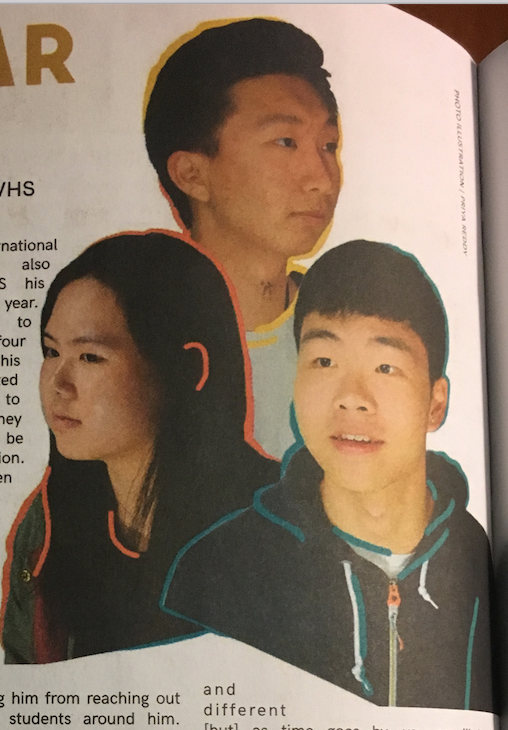

Senior Kcee Yang slightly slouches in her army green jacket, her long black hair framing the shy grin on her face. She chuckles to herself in her seat, recalling the first discussion she had about moving in middle school. To her, a seemingly casual remark set fire to her journey toward independence, displacing herself from her family in Beijing to a new home in America.

“It was a ridiculous reason,” Yang said. “I think I just said randomly [one day,] there’s too much homework in middle school, I said to my mom. I heard that homework in the U.S. [was less].”

Put shortly, she says this expectation was wrong. At MVHS, she trudged through her homework well past the 8 p.m. finish line she maintained in Beijing. She wishes she hadn’t come to the school for its high academic pressure. A soft laugh follows, as she jogs through her past choices in her head. The move from Beijing to San Francisco in eighth grade for a less stressful environment. Another move from San Francisco to Cupertino sophomore year — this time for a more challenging education. The doubts entailed every decision. But she transitioned through it all without the physical company of her parents, moving from one host family to the next.

“I expected loneliness. That happens a lot in international students,” Yang said. “I kind of get used to it now.”

MVHS had its downsides for Yang, but its benefits too. Her first year, she joined the long-held tradition for many international students at MVHS: sitting in the Student Union during lunch. The tables closest to the glass windows has become an unofficial second home for many international students at MVHS. The origins of this tradition is unclear, but the motive has stayed the same: to be around friends of similar backgrounds, sharing in the comfort of each other.

“It’s a good place I would say. I wouldn’t go anywhere else, other than the [Student Union] during lunch,” Yang said. “[It’s] really helpful because for me personally, I don’t really like to talk with people, and knowing there’s another international student, makes me feel comfortable to talk with. I think sometimes I don’t like to talk with the local students because I just think my English isn’t that great. I don’t [want to] cause any misunderstanding.”

This year, Yang sits in the corner of the last table, conversing in Chinese with her friends like senior Charlie Qin, a Chinese international student who also came to MVHS his sophomore year. Their mutual struggle in AP Economics strengthened their friendship this year, and the two sit together every lunch sharing food, laughter and conversation.

Qin’s journey to the U.S. started four years ago when his parents suggested that they move to give him what they believed would be a better education — one they felt would be more well-rounded and less focused on only grades.

Like Yang, when Qin first stepped foot on campus, he felt a sense of loneliness and disconnect from the people around him, his own doubts about his English abilities preventing him from reaching out to the American students around him.

In his personal life at home, with two American cousins, Qin felt this insecurity rise up again. As his cousin’s conversed in fast-paced English, the words blurred together in his ears. He couldn’t bring himself to speak to them in English, slipping back into the familiar tones of Chinese. When he talked to them in English he felt as though he wouldn’t be able to understand and answer back in English.

Qin doesn’t blame this disconnection on anyone, just as Yang internalizes the fear of speaking to native students to herself. Rather than tumbling into a feeling of embarrassment, Qin takes a step back, viewing the problem from two perspectives. He says American-born Chinese students don’t reach out to Chinese international students, just as Chinese students would not go out of their way to talk to foreigners in China. For the international students talking to American students is difficult from the fear of butchering the language, but he also sees how American-born Chinese students feel the same insecurity over their Chinese.

“I try to [talk to American-born Chinese students],” Qin said. “I also don’t like I feel like it’s no need for [American-born Chinese students] to talk to us using Mandarin, it kind of feel awkward. I feel like it’s natural when you talk in English. And I can speak slowly in English but like I can express what I want to express. I think that’s the best way to illustrate this.”

While Qin admits a natural lack of interactions between American-born Chinese students and international Chinese students, the familiarity of American-born Chinese students, due to their shared cultural roots, is not something to ignore. Senior Hugo Liao, who sits one row before Yang and Qin in the Student Union, believes that his parents moved him here due to the large Asian population. And it’s the cultural diaspora that ended up benefitting Liao in the long run.

“I mean, I’m pretty much open-minded. When I came here I’m ready to accept anything new,” Liao said. “But then something surprised me was like, ‘Dude there are a lot of Asians and Indians in this area’ …. I think, as it turns out, it actually did [help me], because there are a lot of American-born Chinese and then a lot of native Chinese as well and it just helped me to blend into this society and learn about the American culture.”

At school Liao found himself making friends with other immigrants from countries around the world — China, India, Korea — forming a connection over their struggles in figuring out how to navigate American culture and school life.

“I will still prefer to hang out with my Chinese friends, not because I’m racist but because we have similar cultural backgrounds like when we hang out together we talked about similar things and then we do similar activities as well,” Liao said. “So it’s completely different, but really cool to have two different kind of activity for me.”

And Qin has found this to be a truth for himself. Two and a half years ago as a second semester sophomore who had just moved from China, Qin couldn’t bring himself to interact much with the American students around him, new insecurities about his English skills holding him back. But as his high school career comes to an end, Qins finds himself more easily slipping into English, to comfortably interact and make friends with other students.

In Qin’s eyes, the initial loneliness and disconnect he had felt when he moved here was just a natural part of the immigration process.

“I mean it’s a time issue. I mean, after like one or two years it will become better and better. I strongly feel that way, [that] it’s just temporary,” Qin said. “When you first come to a different country you feel lonely and different [but] as time goes by, you are likely to learn more and more about the culture and you can have more friends.”

As Qin looks to the future he hopes to stay in the U.S. As a green card holder he feels that he has a really good set of opportunities here and so he does not want to move back to China yet. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Yang plans to move back to China for a gap year right after high school ends.

Two and half years after his move, Liao too has found his place in the MVHS community. Yet he finds himself wishing to be able to visit his friends back in China, who he still keeps in contact with. In the future, he hopes to have a job that allows him travel and maintain a connection between China and the U.S.

“I think it would always be nice for me if I can go back to China for work, maybe [in] some sort of international corporation that I can get into [so] that I can just fly back and forth between the U.S. and China,” Liao said. “I would love to do that because I actually like the weather, the law and the freedom in the U.S., but I also like the culture back in China, like the food in China is just so good I can’t give [it] up.”