Reality through a different lens

April 11, 2018

There’s a certain feeling of unease that creeps into the back of the mind, shifting slightly towards the gut when intuition kicks in. Then suspicion arises. As a stubborn thought makes its way through, constantly poking into the skull, it becomes difficult to shake off the curiosity that comes with your own assurance. It’s as if something, maybe something bad, is happening.

You brush the feeling off and label yourself paranoid, because the reality is conspiracies theories are just theories until proven true.

However, according to AP U.S. Government teacher Ben Recktenwald, there have been countless times in which initial suspicion and eerie intuition have proven true.

An example is the Tuskegee experiment in Alabama between 1932 and 1972, where black men who had syphilis were not given treatment. The government intentionally let the men die to see how the disease progressed over the years. People thought the idea that this was happening was ridiculous, far-fetched. But now they have documents that prove it actually happened.

The real question lies not in whether these ideas are true, but in the initial attraction to them. The alternative oftentimes crosses the line between reality and a seemingly fictional world — and perhaps that’s just it. In times of confusion, when the unknown becomes a source of frustration, the human mind reaches out for an answer. When things go wrong, when things aren’t as they should be, a world outside of this reality is appealing, comforting and, at times, entertaining.

Honors American Literature, under English teacher Mark Carpenter, is as much a class about dissecting literature, as it is about understanding social issues with a critical eye. In a typical lesson, Carpenter poses a question in his calm, yet assertive voice, shuffling a stack of cards to some students’ heightened nerves. Each card contains a student’s name, used when the class dissolves into periods of silence. Once one student spearheads a discussion, however, Carpenter strolls from one end of the classroom to the next, listening keenly to their thoughts. Insights on classic novels like “The Scarlet Letter” to a contemporary book like “Citizen: An American Lyric” bloom in the air. Literary elements naturally weave into current events that students observe or experience daily. In one lesson, a student spilled her own account of gender inequality, after reading “The Confidence Gap” by Russ Harris. It’s at times like this that he slowly nods his head in support.

Carpenter tries to moderate and encourage contrasting opinions, but he stills feels that he must draw the line somewhere. For the Factoid Friday projects this year, in which students formulate evidence-based arguments to qualify a controversial social issue, Carpenter no longer allowed topics such as vaccines and affirmative action. In previous years, he watched students, who must speak both for and against their chosen topic, stress that vaccines cause autism, which has been disproven, and use racially-biased sources to refute affirmative action. While they had no devious agenda — only “poor research habits,” according to Carpenter — he could not let his classroom be a channel for spreading false information.

“I’m never going to let a student do a Factoid Friday project on ‘Is the earth really round?’, ‘Is evolution real?’, you know, none of those things. No ‘whose-inauguration-was-bigger?’” Carpenter said. “I try, when I can see them coming, to cut off opportunities for alternative facts to come into the discussion in the first place.”

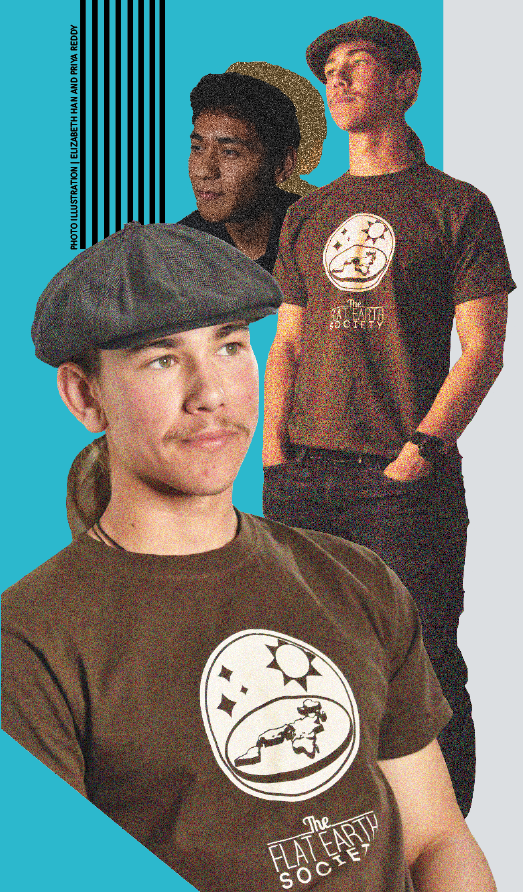

And while Carpenter dispels such ideas in his classroom, junior Georgiy Bondar finds himself meddling with the alternative. At age two, Bondar found himself in a new environment moving from Russia to the U.S. Now as a 16 year old AP Physics C student, with long blond hair pulled back into a low ponytail, he tops off his look with a newsboy hat and t-shirts that turn heads at MVHS. One day, the Trump Pence campaign sign is on his shirt. The next, a diagram of the flat Earth emblazoned on his chest.

His curiosity toward alternative theories grew once he noticed an inconsistency in his education. As a child in elementary school, his main sources for information were his teachers and his parents, and often the two didn’t align. Bondar noticed this specifically when it came to history. He was able to see how his parents, who grew up in Russia, were taught social science in a completely different manner than he was, and in doing so was better able to recognize the spin that was placed on the things he was taught in school.

“In school a lot of times, they tell us something that doesn’t seem true and then my parents would say something else because they’ve learned history in a completely different way,” Bondar said. “Some of the things they’ve taught [me] are different from what they teach here, and I mean, that’s more regarding the Soviet Union and the U.S., but in that sense I’ve learned to be skeptical.”

Such a paradigm shift cut through Carpenter’s early life as well. When he entered his Catholic high school, he found discrepancies between his mother’s religious teachings and the Bible. His mother grew up before Vatican II, during which Catholics used the Latin Bible. With no English translations available, she had relied on the words of her priest as her only source, which were then passed down to Carpenter in his childhood. Carpenter speculates that, perhaps due to this upbringing with no means to fact check her information, his mother gives more credulity to those who speak with authority over actual institutions.

Carpenter, who is no longer Catholic, now describes his mother as a skeptic of authority. In her occasional phone calls to Carpenter, a resentment of the system belies her words. She believes that universities are a brainwashing tool of extreme liberals, an herbalist has equal standing as a doctor and an oil executive knows just as much about climate change as a scientist. To Carpenter her sources seem dubious. She discounts news sources like The New York Times, The Washington Post or NPR, which have become Carpenter’s primary selections after the abundance of fake news in the Trump era.

He tried to pull his mother out of her reality initially. When she told him the pope had endorsed Trump in 2016, he tried to correct her — that the pope in fact denounced Trump. But instead of landing on the same page as he had hoped, they only moved further away from each other in their beliefs.

“It’s always a losing battle. My belief that I can change your mind is a fringe belief because I’ve seen the studies that when shown evidence that condemns a firmly held belief, people hold more tightly to those ideas,” Carpenter said. “I’ve stopped appealing to authority, science, journals, sociology and speak from experience … that I have a group of friends that is more diverse in background and experience than my mother does.”

Carpenter doesn’t know if his mother is entirely convinced by his personal accounts that draw in ideas that she guards herself from. Nevertheless, he continues, with hopes of bringing her closer to his reality.

This journey lies in Bondar’s own life as well — only it extends to Bondar’s classmates, not his family. Over time, Bondar has come to his own realization that people tend to follow what they are taught in school without much questioning. He has rejected this by consistently questioning authority and that which is presented as fact, a mindset he believes has to be learned.

“Not everyone can learn to disassemble the beliefs they’ve been taught from their very childhood,” Bondar said. “Because it’s one of those things that’s so deeply ingrained at this point.”

Understanding that there are differences in the way people perceive the world, some in the mainstream and others more fringe, Bondar enjoys showing the more alternative beliefs to those who may not see them.

So he plays a sort of game. He introduces the beliefs to his classmates, with an air of mystery in his own stance between the fringe and mainstream. He enjoys making people realize that facts can be questioned. He wants to challenge their belief system. And the game includes a crucial component: the flat Earth theory.

Junior Joseph Del Mundo, a long time friend of Bondar, first learned of Bondar’s apparent interest in the flat Earth theory when the two were in the same world history class.

“We were just having the normal banter that friends usually have, you know, like jokes. The flat Earth theory came about and we had a really nice, philosophical conversation and debate about it. And he ended up converting me,” Del Mundo said. “He converted me to trolling people into the flat Earth theory.”

Bondar and Del Mundo’s friendship dates back to elementary school and has been maintained through a common interest in a variety of topics — history, the card game Magic: The Gathering, political parties — and in pranking people. “Trolling,” to Del Mundo, is an integral aspect of Bondar’s personality. And though this interest has remained constant, for Bondar in particular, the method through which they decide to troll has changed significantly.

Despite not actually believing the Earth is flat, it is crucial to Bondar’s game that others think of him as a believer. Del Mundo has also picked up the practice of pranking others by spreading unconventional ideas to those who will listen. For both Bondar and Del Mundo, the goal is to convince the listener that they are believers, and in the process make the listener think about ideas that are considered outlandish.

Now, the two don’t begin by introducing the flat Earth theory. Instead, like a coach easing someone into the shallow part of a pool, they begin with a smaller conspiracy theory and work their way up to the flat Earth theory.

“It doesn’t start off with the flat Earth theory, right? That’s the end game, basically. I have to convert people, first with more acceptable beliefs, like chemtrails from aircrafts,” Del Mundo said. “I have to work my way up. Flat Earth is like the top, the cream of the crop basically.”

Bondar and Del Mundo require such buildup in their game, due to the more obscure nature of the flat Earth theory. But contributors to The Flat Earth Society (TFES) present their beliefs with firm conviction. Some within the society believe there is a dome covering the entirety of the flat Earth, while the predominant idea is that an ice wall surrounds the Earth, preventing the oceans from flowing off the edge. To members of TFES, there is no such thing as a flat Earth conspiracy, but rather a space travel conspiracy concocted by NASA to brainwash Americans.

“It’s one of those things that you never really think about,” Bondar said. “But then you start looking into it, and you read what other people have written on it, and there’s a lot of other experiments that people have done. There’s a lot of ideas that make it much more believable than it sounds at the start.”

Keep in mind, Bondar doesn’t actually believe in the idea.

According to the Flat Earth Wiki (FEW), there are many ways to prove the earth is not round and many ways to combat the proof provided to show that the Earth is spherical. For example, the FEW states that airplanes are unreliable for proof that the Earth is round, since the windows are heavily curved and the minimum height needed to see the earth’s curvature is 40,000 feet — 5,000 feet higher than the average aircraft cruising altitude.

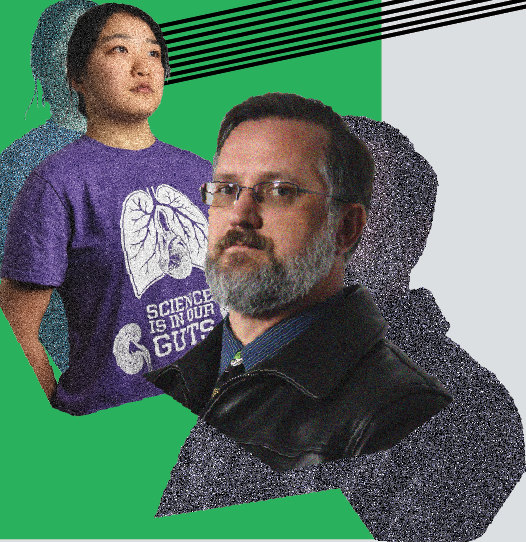

To senior Jasmine Wang, who interned at the Center for Space Research at the University of Texas in Austin last summer, the notion of a flat Earth is far-fetched.

“When I first heard of it, I thought it was a joke,” Wang said. “If the Earth was flat, nothing would work — so many scientific instruments are based on the rotation and the shape of the earth. It’s obviously a really dumb opinion that’s not scientifically based, and it’s sad because it shows a lot of people are very willfully ignorant.”

According to Wang, common occurrences in nature would not be possible if the Earth were truly flat.

“For example, compasses wouldn’t work if the earth was flat,” Wang said. “It would take some crazy violations of the laws of physics for it to be flat and not to fall apart, and for everything on the earth to work if the Earth was flat. And we wouldn’t have seasons, we wouldn’t have so many other things.”

Despite disagreeing with flat Earth believers, Wang still respects their thoughts because she believes their ideals have minimal effect on the scientific community.

“It’s funny, obviously it’s freedom of speech,” Wang said. “People who are ignorant enough to accept those beliefs, it doesn’t do that much harm [to the scientific community]. It’s just mind blowing. People who know the Earth is round don’t have the right to oppress the voices who believe the Earth is flat, even if it’s dumb.”

While Bondar’s pranks circulate in real life, the Internet has become a hub for the unconventional. Sometimes Carpenter believes that the Internet can play a significant role in the presence of alternative ideas, as it influences the way society communicates.

“The Internet allows people with narrow areas of interests, specialty or fringe, the opportunity to connect over great distances,” Carpenter said. “It also gives a megaphone to any opinion. Those two things are great things about the Internet. But it makes fringe beliefs feel more valid to people that hold them.”

Bondar feels similarly about the Internet; specifically, that people can spread ideas without having to leave the comfort of their home.

“There are books you can read and other stuff, but again you find out about all this stuff from the Internet,” Bondar said. “So if an idea is unpopular, really any idea, you can find more about it through the Internet.”

Recktenwald believes that the Internet is akin to a double-edged sword, one that promotes freedom of speech while also being a tool for censorship.

“The Internet has been a tremendous tool for good, but also a tremendous tool for crime and for awful things,” Recktenwald said. “And for oppression. For example in China, the Chinese government used the Internet to control people how to think and say and spy on people. Some of the conspiracy theories are saying that the U.S. government is doing that too.”

Though Bondar looks for a reaction from many of his victims when they realize that he is “trolling,” he is unwilling to fully commit to revealing the extent of his deceit. Instead he plays coy, offering a shrug of the shoulders or a quick twist of the mouth as a way of leaving some uncertainty as to where his true beliefs lie.

Just as Bondar uses these games to convey his more fringe beliefs, he goes about the same way to share his political stances. And while he derives a certain type of enjoyment from seeing the reactions to these opinions, the difference lies in his conviction. With his political beliefs, Bondar is entirely serious, and at times has had discussions about them with fellow students and the occasional teacher. Bondar believes that since his political beliefs seem more real and as a result more believable to the people around him, the reactions are stronger and more emotional.

Bondar never enters these debates with the goal of convincing the other party. He knows that when people have political debates it is unlikely that either participant will end up changing their views.

“That’s the thing with political debates, you never convince the other person you’re right. You just kind of get mad and leave at one point, but you know again it’s not about convincing the other person, it’s getting the other person to actually think about it,” Bondar said.

Bondar and Del Mundo have found somewhat of an audience to listen to their beliefs in the people around them. They listen, not so much because they believe, but more because of a fascination about beliefs that are out of the norm.

“People want to hear something, right?” Del Mundo said. “Not just because they believe in it, but also because it’s funny. It’s just so absurd, it’s comedy [and] they’re interested.”

And for Bondar, that is enough.

“If I talk to them and introduce my viewpoint, their first reaction might be, ‘Oh, that’s insane. That’s stupid,’” Bondar said. “At least you’re still thinking about it and hopefully after the fact, they’ll still have that thought in their head, and they may not necessarily change their views but at least they’ll think about the things more.”