Symphony of senses: how synesthetes experience the world differently

The perspective of a synesthete

March 8, 2018

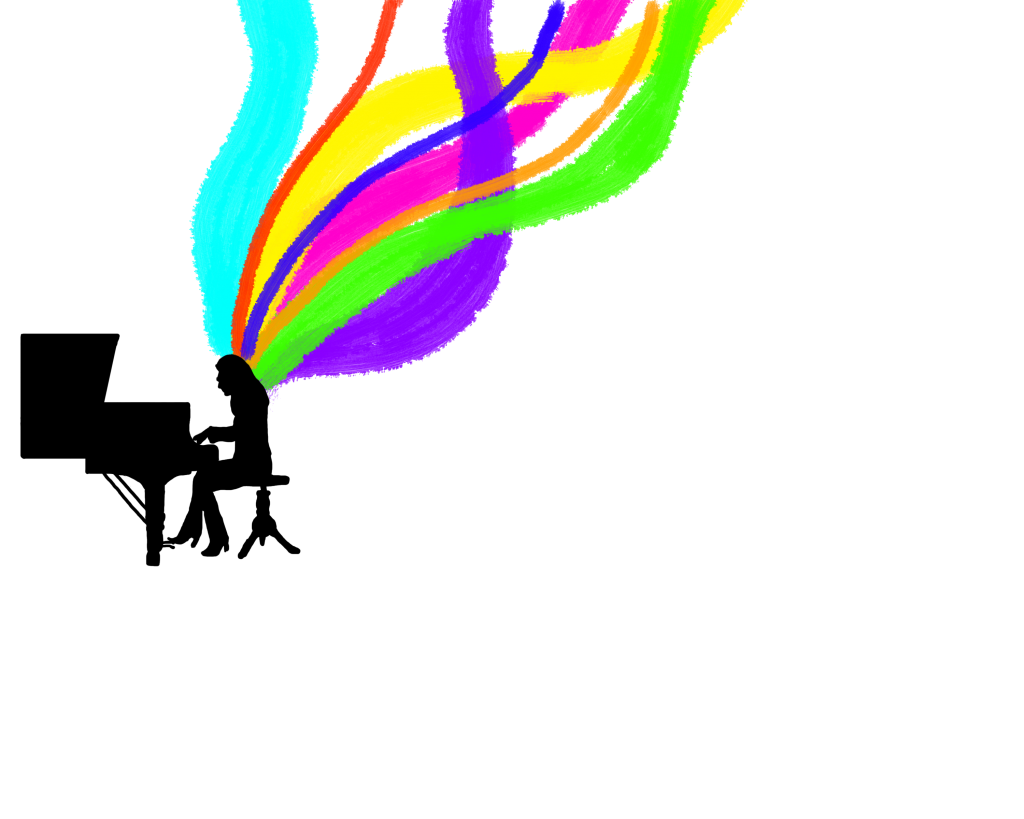

She sits on the cool wooden bench of the piano, her fingers grazing the smooth keys. She lifts her hands and begins to play. To her family members scattered throughout the house, the chorus of notes creates a flowing melody and lively tune. To her, it is much more. Colors and light fill her vision, illuminating the space of her living room.

At first, all she can see is dark red. Gradually, as the tempo of the Chopin’s “Fantaisie-Impromptu” becomes faster, the red grows brighter and more intense. All of a sudden, her mental canvas turns a stormy blue, and her fingers are moving more slowly than before. She sees yellow now, with spots of pink. Before the slow section of Chopin’s piece finally ends, her mind is flooded with a light teal color that grows increasingly darker as she plays faster. Black abruptly turns into a dreamy white color that tempts her to close her eyes and fall asleep.

This is what senior Anisha Kollareddy experiences when she hears music. According to the Scientific American, synesthesia is a blending of the senses in which the stimulation of one sense leads to the stimulation of another. According to Kollareddy, synesthesia has been a part of her life for as long as she can remember, although she was unaware that it was a special condition until her junior year.

“[My best friend’s] first reaction was ‘You’re insane,’” Kollareddy said. “But then we did our research and found out that it’s rare, but I’m not insane. So because I only found out it wasn’t normal last year, I’m still learning about synesthesia as I go. I always had thought that everyone associated things with colors like me.”

Kollareddy has grapheme color synesthesia, where she can see colors in numbers and letters, as well as chromesthesia, where she can see colors in music. Similar to Kollareddy, most synesthetes experience several types of synesthesia. For example, Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital neurologist and researcher Joel Salinas experiences multiple forms of synesthesia, including an extremely rare type called “mirror-touch synesthesia.”

According to Salinas, mirror-touch synesthesia means that he can feel others’ pain. If he sees someone get poked in the cheek, he feels a poke on his cheek in the exact same location on his body.

“Because of mirror-touch synesthesia, my brain automatically sees others as a part of me,” Salinas said. “Sometimes I actually have to focus on my own body so I don’t confuse your feelings too much as my own, and so I don’t forget about myself and my own feelings.”

As a child, Salinas had no idea that he had synesthesia, but he was aware that something was different about him.

“I just chalked [my behavior] up to being a weird kid,” Salinas said. “As a child, I was incredibly particular about how I colored letters and numbers. They had to be their ‘right’ color. ‘A’ has to be red. ‘B’ has to be the right shade of orange. The number ‘1’ has to be light yellow. Fussing over these things, I’m sure you can imagine how often my parents rolled their eyes.”

Synesthesia is fairly uncommon; according to the American Psychological Association, synesthesia affects one in 2000 people. Many people are unaware of what synesthetes really experience. Because of this lack of knowledge, best-selling author Wendy Mass wanted to spread awareness through her children’s novel “A Mango-Shaped Space” even though she had never personally experienced the condition.

“I didn’t know anyone with synesthesia before I started writing the book, but I have met a lot of lovely synesthetes along the way,” Mass said. “A lot of their stories and experiences made it into the novel. I loved the fact that there was a way of perceiving the world that I didn’t know about, and that people couldn’t see from the outside.”

“A Mango-Shaped Space” became extremely popular and has been nominated for over 14 awards. The book is about Mia Winchell, a 13-year-old girl who sees colors within letters, numbers and sounds. Throughout the story, she learns how to navigate through her condition and incorporate herself into society.

Although Winchell’s story is fictional, it represents the lives that many synesthetes experience. To Salinas, having and understanding synesthesia is something that challenges him everyday.

“I don’t [see] myself [as] overcoming synesthesia, so much as I see just as an intrinsic part of how I experience the world,” Salinas said. “As you can imagine, in the hospital, having mirror touch can be a bit of a challenge sometimes, but it also helps me help others.”

Mass mentions that there are certain disadvantages for those like Kollareddy and Salinas, but there is also an abundance of positive aspects of having synesthesia.

“I do think math and languages in general are harder for some synesthetes, but of course not all,” Mass said. “Memorizing things, likes dates in history and phone numbers, are generally easier because they can remember how the colors are strung together as well as the numbers or letters.”

According to the New York Magazine, synesthesia is most common among creative artists. Because of her ability to see music in different colors, Kollareddy loves to play piano. To Kollareddy, songs mean more than notes and sounds, and her synesthesia helps her compose music.

“I like to mash music,” Kollareddy said. “Synesthesia is a really big part of music for me because when I bring together pieces, I see the colors flowing together and it just makes sense. Different colors go together and my favorite songs are like paintings in my head.”

Not only does Kollareddy associate music, letters and numbers with colors, but she also perceives people around her as colors as well.

“When I first meet someone, I would say they have a basic color,” Kollareddy said. “It just starts out like that. And I get to know people more, there’s more facets to them, more sides, and I know the depth of their personality, so it adds on color.”

Synesthesia enables people to better empathize with others’ concerns and emotions. Having mirror-touch synesthesia allows Salinas to have a higher understanding of others, a lesson he hopes to teach others as well.

Although she isn’t a synesthete, Mass encourages others to embrace the condition and accept themselves.

“I wanted to tell a story about needing to learn that we all see the world differently,” Mass said. “We all have something that makes us unique and different, and that’s something to celebrate and not to feel bad about.”

Kollareddy believes that synesthesia isn’t something to be ashamed of.

“[Synesthesia’s] positive,” Kollareddy said. “I see all the colors in my head. Rainbows are associated with positivity and happiness. That’s kind of how synesthesia helps in my life.”