he steps are easy. You order a kit and spit into a plastic tube. Six to eight weeks later, the results come back. They outline your ancestry and sometimes health results as well, which tell you diseases you may be at risk for, among other things. But the simplicity of the process belies a complicated ethical dilemma that stems from DNA testing-based sites like 23andMe.

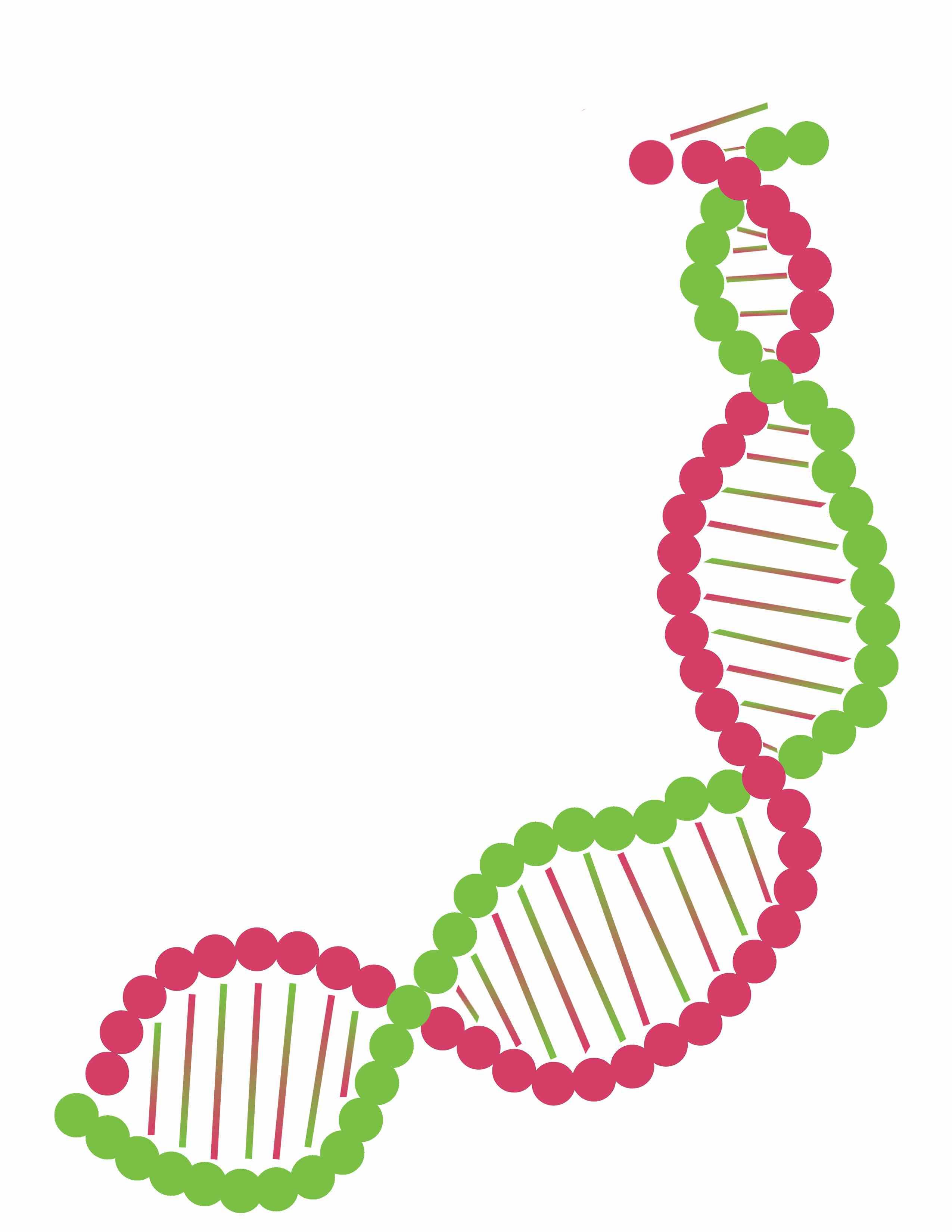

According to AP Biology teacher Renee Fallon, DNA testing can be a slippery slope, although the concept behind companies like 23andMe are well-intentioned. These companies are part of a field called pharmacogenetics, which is the study of differences in DNA that can impact an individual’s response to various drugs. Fallon explains that if a drug works on 20 percent of the population, the goal of pharmacogenetics would be to find out which 20 percent it works on, and why it works on those people.

“Companies like 23andMe hold the promise of finding that out, so you could walk into a doctor’s office, get a genetic test for your specific whatever and get a drug that we know works on you, rather than subjecting you to really nasty drugs that aren’t going to do you personally any good,” Fallon said.

History teacher Eric Otto used 23andMe, but for him, it didn’t pose as much of an ethical dilemma. Rather, his hesitations stemmed from deciding whether to use the health and ancestry package or just the ancestry package.

23andMe’s website says the health testing is FDA approved to test whether a person is a carrier for certain conditions, or how genetics may put an individual at risk for certain diseases. The knowledge of being at risk for a serious disease could have a large impact on an individual’s lifestyle, but in the end Otto chose to pay for the combined health and ancestry package anyways.

“The genetic stuff … could reveal some pretty frightening results that would cause you to think twice about your health and you know, your future,” Otto said.

An additional concern that Fallon raises is that sending in DNA also means that an individual sends in the genetic information of others family members. Even though she can consent to sending her DNA in to be tested, the rest of her family can’t. And they may not want parts of their DNA sequence stored online, or know what her DNA results could suggest for them.

“When you study your own genes, by definition, you’re not just studying your own and that’s the main thing that holds me back,” Fallon said. “If I could isolate and just study mine, I’d probably be willing to do that.”

For senior Sydney Olay, who took 23andMe’s ancestry test a month ago, the concern that Fallon mentioned was eased by the fact that her parents supported the decision to take the test. Her father was the one who purchased it after it came up jokingly over dinner. Olay’s mom plans to take the test in the future as well.

Otto’s apprehension regarding the health testing was was alleviated when he received his results and found them unalarming. As for his ancestry results, he said he’s always been fascinated by family history, and just seeing the percentages themselves was a huge revelation to him.

“Usually, you take a look at like your grandparents and say ‘ok well, you know, I have a grandparent of Japanese ancestry, I have a grandparent of German ancestry, a grandparent of you know Mexican-indian ancestry,’ and then of course that all translated to my parents,” Otto said. “And you would think based off of that, you could somehow in your mind say that ‘okay maybe I’m a quarter this or a quarter that or whatever but I guess it doesn’t work that way when you get a report like this and it’s like ‘oh there are actual percentages out there.’”

Olay also found herself surprised by her results — she’d expected to be roughly half Chinese and half Filipino, since her mom was Chinese and her dad was Filipino, however that was not the case.

“I was shocked, I was like ‘what?’” Olay said. “It was just so surprising to me, because I was like ‘How can I be 95 percent Southeast Asian when my mom’s full Chinese?’ so that’s what really shocked me.”

For Olay and Otto, the knowledge of their own ancestry that they received outweighed their concerns, although they do recognize why DNA testing may bring up ethical questions.

“You know there are other, I think, more important things out there that could get stolen and used against you, like your social security number or your identity for that matter,” Otto said. “And so, you know, just a little bit of spit for me wasn’t really that big of a deal.”