Kendrick Lamar has reached a level of prestige almost previously unimaginable for any Compton-based rapper from the last two decades. Fans and music enthusiasts alike hail him as one of the most significant artists of his generation, with the rich storytelling on his second studio album Good Kid, M.A.A.D City and his ability to detail harsh racial struggles on his third, To Pimp a Butterfly. He has already been honored with more than 20 nominations by The Recording Academy, most notably presenting him the Grammy Award for Best Rap Album for To Pimp a Butterfly — an album former president Barack Obama claimed as the generation’s best.

On March 23, Lamar surprised fans of rap with an unexpected release. “The Heart Part 4” was released onto Soundcloud and ended Lamar’s two-year hiatus from studio discography. The song followed the pattern Lamar uses for his album announcements — he adds another part to his “The Heart” chronology before the release of a new album. On March 30 Lamar released “HUMBLE.,” a single off his upcoming album DAMN., onto major streaming platforms along with a music video showcasing Top Dawg Entertainment’s excellent cinematography.

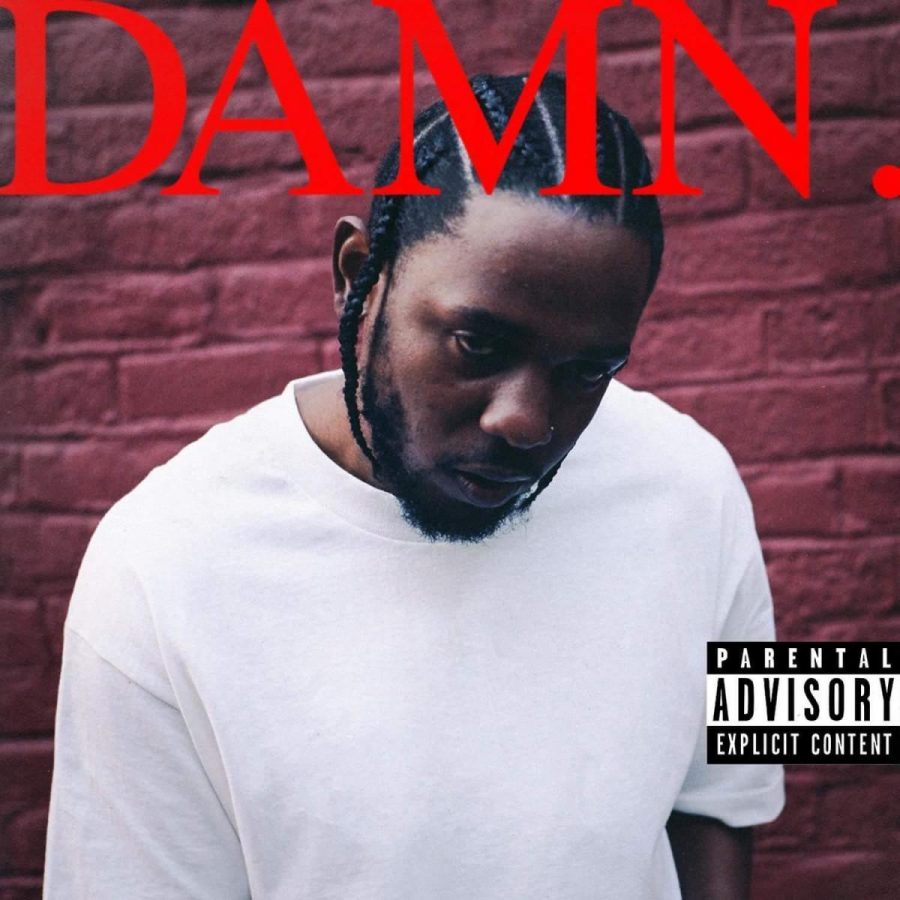

Frame taken from Lamar’s “HUMBLE.” music video released on March 30. Lamar references the Bible when the apostles had fire over their heads after Jesus visited them post-Resurrection.

Although Lamar has his fair share of admirers, he can’t stop obsessing about those who don’t on DAMN.. In July 2015, a Fox News panel mocked his song “Alright” which has become a modern day civil rights anthem, criticizing a line about police violence: “And we hate po-po / wanna kill us dead in the street for sure.” Lamar pins this snippet on the second song from the album, “DNA.” He also fixates on Fox News panelist Geraldo Rivero’s claims that “hip-hop has done more damage to young African-Americans than racism in recent years.”

When his music is boiled down to the one provocative line from “Alright” as if it was its primary message, it’s an insult to Lamar and he snaps back, “Somebody tell Geraldo this n**** got some ambition,” as he raps on “YAH.” Lamar is a lyricist; he puts his life skillfully into words and draws a significant meaning in his tracks.

“I put my lyric and my lifeline on the line.” – LOYALTY.

The album’s sounds are more similar to current hip-hop trends than 2015’s jazzy To Pimp a Butterfly. DAMN. features hard-hitting drums and loud snares, a trend similar to the likes of Atlanta’s hip-hop subgenre, trap. “YAH.” uses wavy beats to battle Rivera’s words and muses on Biblical claims. “LOYALTY.” drops Lamar’s new nickname for the album, “Kung Fu Kenny.” “LOVE.” and “LUST.” explore the conflict between the physical and the emotional, with “LOVE.” shining in a way to bring out the plush synthesizers and the stuttering drums in the production.

“Why God, why God do I gotta suffer? Pain in my heart carry burdens full of struggle” – FEAR.

The two songs that follow, “XXX.” and “FEAR.,” combine personal with political narrative in stunning fashion. Lamar is able to turn America’s woes of racial equality into a moment of prayer and self-reflection, with U2 lead singer Bono’s soothing voice acting as a release for Lamar’s questioning of heaven: “Is America honest, or do we bask in sin?/ Pass the gin,” Lamar slowly recites over a staggered bassline. During the latter half of the song, Lamar explores three instances of true terror at ages seven, 17 and 27, using his lyrical ability to fully depict different characters, each of whom is fearing for their life. It’s a striking song that demonstrates Lamar’s personality, making his music relatable and resonant.

The keyboard bounce of “HUMBLE.” and the chant of “DNA.” show Kendrick in his element, reminiscent to his Compton former, Eazy-E and Mike WiLL beats. The production is clean yet schizophrenic, often putting two or three synth loops per song and switching tempos mid-track.

Frame taken from “DNA.” music video released on April 18. In the music video, Lamar is chained to a desk to symbolize the criticism he has received over the years from Fox News.

The album ends with the final piece of the Top Dawg Entertainment puzzle, a label built off of Compton artists that ended up delivering the best rapper of the generation. When “DUCKWORTH.” ends with a gunshot and the seamless loop back to track one, DAMN. is written by a Lamar who had no father to teach him how to avoid the sinful temptations of the streets.

Similar to its predecessors, DAMN. is packed with thoughts, anecdotes and anxieties. This time, however, Lamar doesn’t try to build a bigger narrative. Each song tells a story of its own. In “DUCKWORTH.,” he details the story of his father and Anthony “Top Dawg” Tiffith whose paths cross over KFC biscuits. The storytelling is delivered with such precision and detail that it can’t possibly be true — it’s the storytelling no one else in the rap game is doing at a level like Lamar – he is making this kind of art substantial and virtuosic. He doesn’t wrap a tidy bow around the album; instead, he allows every idea to stand on its own.

“Whoever thought the greatest rapper would be from coincidence?” – DUCKWORTH.