Her feet hit stone and slipped.

Near the river below her, people got off boats and trains to begin the long march up the golden hills to the peak of the hill, where Mauthausen sat. They’d driven up part of the way, in an air-conditioned bus, drinking chilled water by the liter, and watching the scenery pass by. Once she’d gotten off and given up the cool embrace of the air conditioning for sweltering heat and a stone paved path, her journey began.

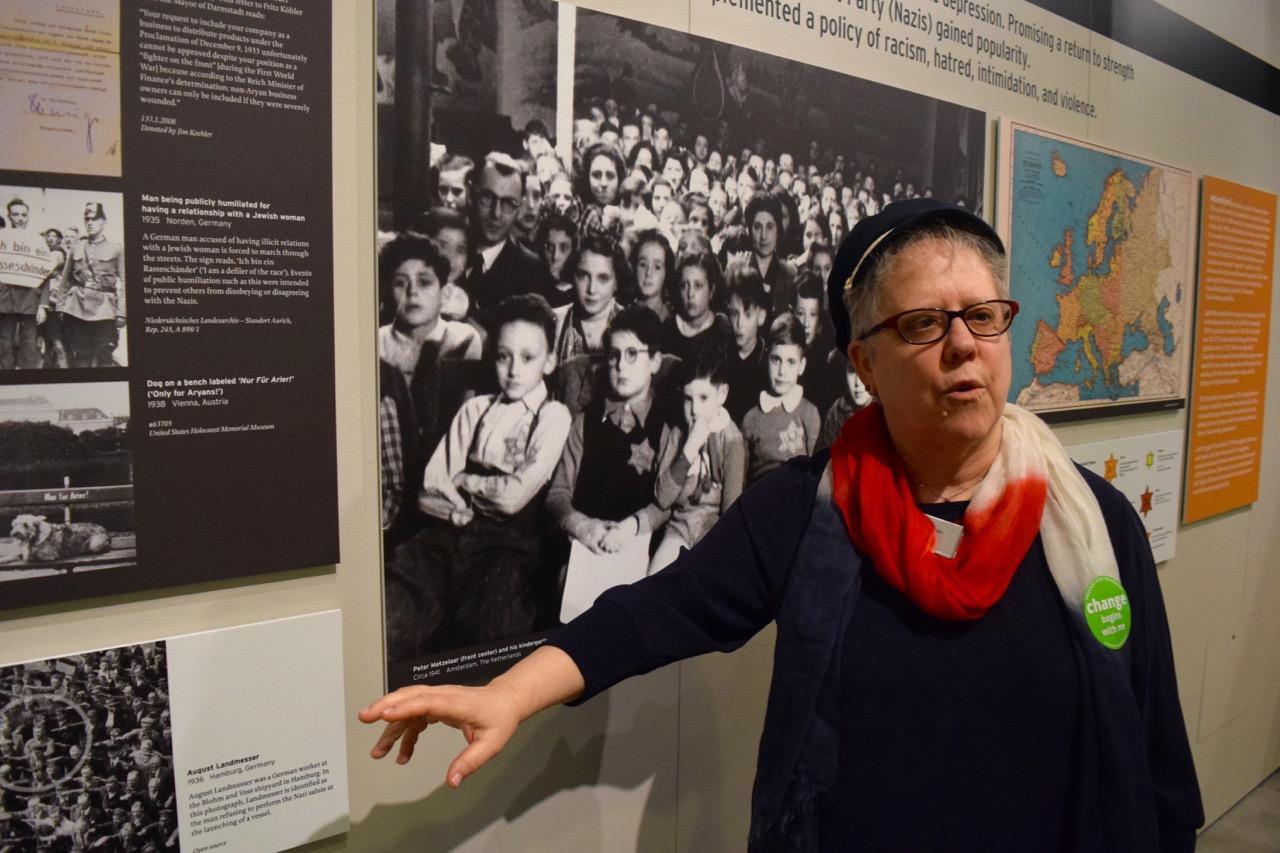

The stone path beneath her sneaker-clad feet was slippery even in the heat of summer. It was one of the few details volunteer docent Linda Elman remembers from the last day of the trip she took last summer to see Holocaust sites throughout the Netherlands and Prague. They were visiting Mauthausen, a quarry where Jewish people were sent under Nazi rule. The trip and the visit to Mauthausen for Elman was a turning point in her life.

“I’m a crier, and until then I could do things just kind of dispassionately. I can’t be dispassionate now about anything related to Holocaust pain,” Elman said. “And I’m a feeling person and so it makes it harder for me to read books. I need glasses to see print and my glasses get all messed up with tears.”

As she walked up the path the things she’d seen in the concentration camps she seen in the last few days kept reappearing in her mind. She spent most of the day in a state of shock.

“It was the pain of walking the path [in] terrific heat, without water. It was trying to walk on a path out towards the quarry and it was paved in rocks [and] all I could think about was how hard it was just to walk so I think for me it’s just feeling, such a slight sense of the pain must’ve been,” Elman said. “I’m in pain and I’m trying and my pain is one millionth of what these people [felt] so I think that’s what moved me the most.”

For Elman, this connection to others has played a big part of her life. As the granddaughter of Jewish immigrants who’d come to the U.S. in the 1910s, and having attended an integrated high school before any movements in the 60s made such a thing commonplace Elman has seen the lingering effects of routine discrimination first hand. But in Seattle, where her family had settled, attending Garfield High School, she learned to not notice. To not pay attention to race or skin color or religion and instead focus on other defining characteristics.

For Elman, this connection to others has played a big part of her life. As the granddaughter of Jewish immigrants who’d come to the U.S. in the 1910s, and having attended an integrated high school before any movements in the 60s made such a thing commonplace Elman has seen the lingering effects of routine discrimination first hand. But in Seattle, where her family had settled, attending Garfield High School, she learned to not notice. To not pay attention to race or skin color or religion and instead focus on other defining characteristics.

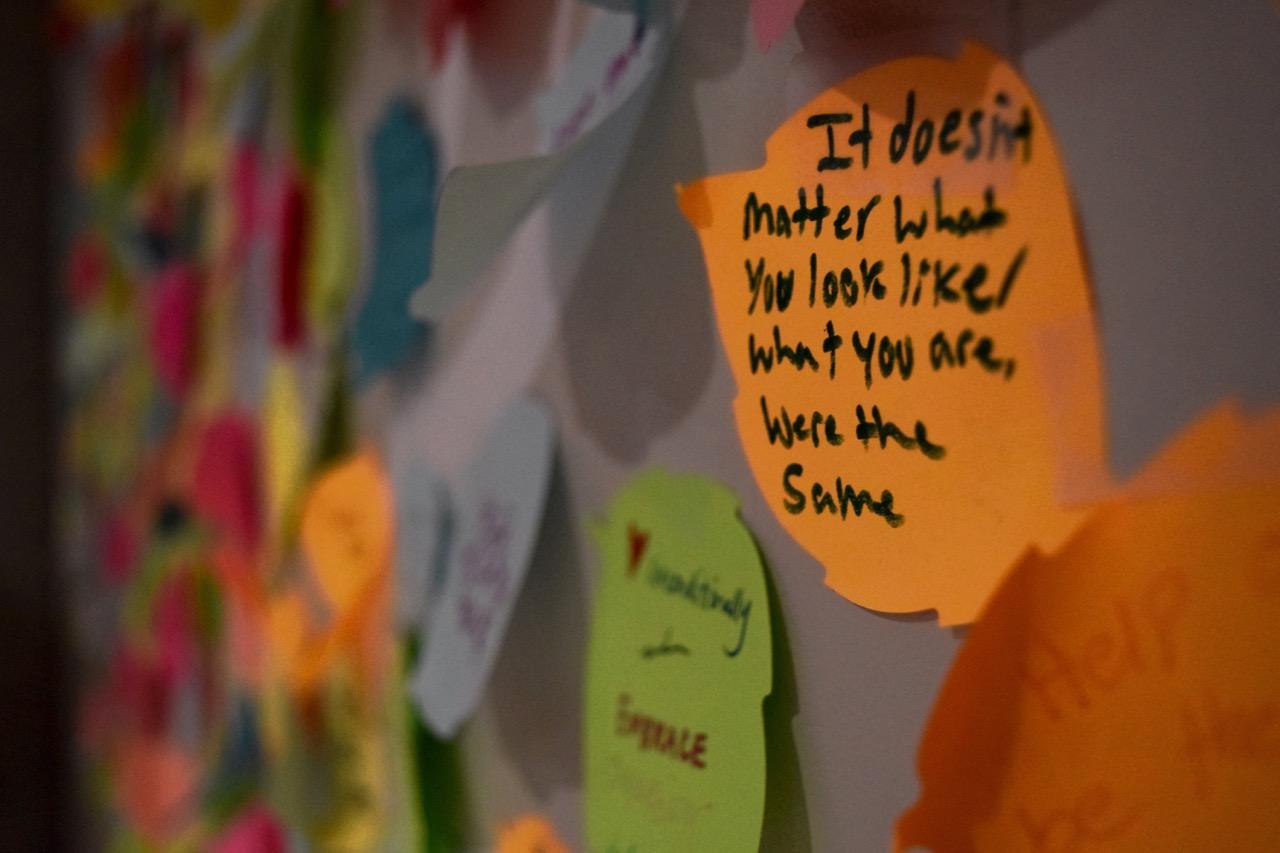

“We were Jews, there were a lot of Asians in my class, the majority were African-American, but we all just sort of got along and I thought that was the way it was supposed to be,” Elman said. “So when I get these stories of people being isolated for a characteristic, it just never made sense to me — to me, it’s the human-ness of all of us.”

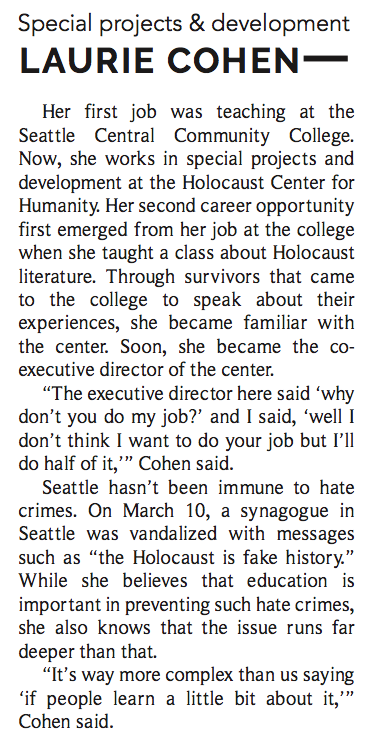

Elman has watched and listened as those around her share their stories of isolation and discrimination because of physical traits or religious beliefs. She’s listened as Holocaust survivors talk through their experiences — as friends and family shared the things that had happened to them she’s listened and learned.

Before working as a volunteer docent at the Holocaust Center for Humanity, Elman worked for years in the public school system, spending time disaggregating data by external characteristics. It bothered her a bit, but she always focused on looking forward.

“It always made me ask the question ‘ok, we’re doing this disaggregation, how can we make sure everybody will have the same outcomes,’” Elman said.

“It always made me ask the question ‘ok, we’re doing this disaggregation, how can we make sure everybody will have the same outcomes,’” Elman said.

As a teaching assistant, she saw something quite the opposite when she worked at a summer camp with a group five year olds. There was only one African-American girl in the group — an obvious minority. Yet when the when one of the children described her, their description was never based on her skin color. To that five-year old girl, that was an irrelevant difference.

“One of the kids was trying to tell me something about her and she described her by the color of her shirt and by the shorts her was wearing,” Elman said. “It never occurred to this five year old to tell me that the girl she was describing was black.”

For Elman the common thread of these relates back to her Jewish roots. It brings her back to“N’shama,” the Hebrew word for soul.

“It’s really this whole theme of the other — you create the other. And there is no otherness here, we’re both humans we have the same n’shama, we have the same soul. You have your soul, I have my soul. They’re both nice clean pure souls and the the other differences are trivial, if you think about the human-ness that we share.”

A montage of Elman and displays at the Holocaust Center for Humanity. Footage by Priya Reddy. Edited by Aanchal Garg.