The building is only one story tall, but stretches so far in both directions that it seems massive. It sits silently at the edge of a cul-de-sac, a one story concrete behemoth framed by grey steps and a tall silver flagpole. The large glass doors that crown the top of a short flight of stairs swing open as a man steps out.

Rohit Jain stands in front of the Santa Clara U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Field Office after completing his citizenship test. Jain immigrated to the United States from India over 10 years ago, and is still in the process of receiving his citizenship. But he’s almost done: in two weeks, he will return to the USCIS for an oath ceremony and become a U.S. citizen.

However, Jain’s happy demeanor and his upcoming citizenship contrast recent activity in the White House. Over the past six weeks, President Donald Trump has signed 12 executive orders, including plans for the construction of a wall along the US-Mexico border and a complete ban on immigrants from seven Middle Eastern countries — Iran, Iraq, Yemen, Syria, Sudan, Somalia and Libya. Shahab Ahghari is an immigrant from Iran, and has been living in the U.S. for more than five years. He still has family in Iran, and since there isn’t an American embassy situated there, Ahghari’s uncle was forced to travel to an adjacent country in order to obtain a visa to visit his family here in the U.S. “We sent him an invitation [to come to the U.S.],” Ahghari said. “But he was already [in another country] when the [ban] happened. He just couldn’t do anything.” Despite this personal experience with Trump’s immigration policy, Ahghari is still certain his citizenship will be completed and his family will not be affected. “I kind of like the approach that Donald Trump is using,” Ahghari said. “I think this government is just a little more extreme. But I’m hopeful.”

It is amazing how often I am right, only to be criticized by the media. Illegal immigration, take the oil, build the wall, Muslims, NATO!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 24, 2016

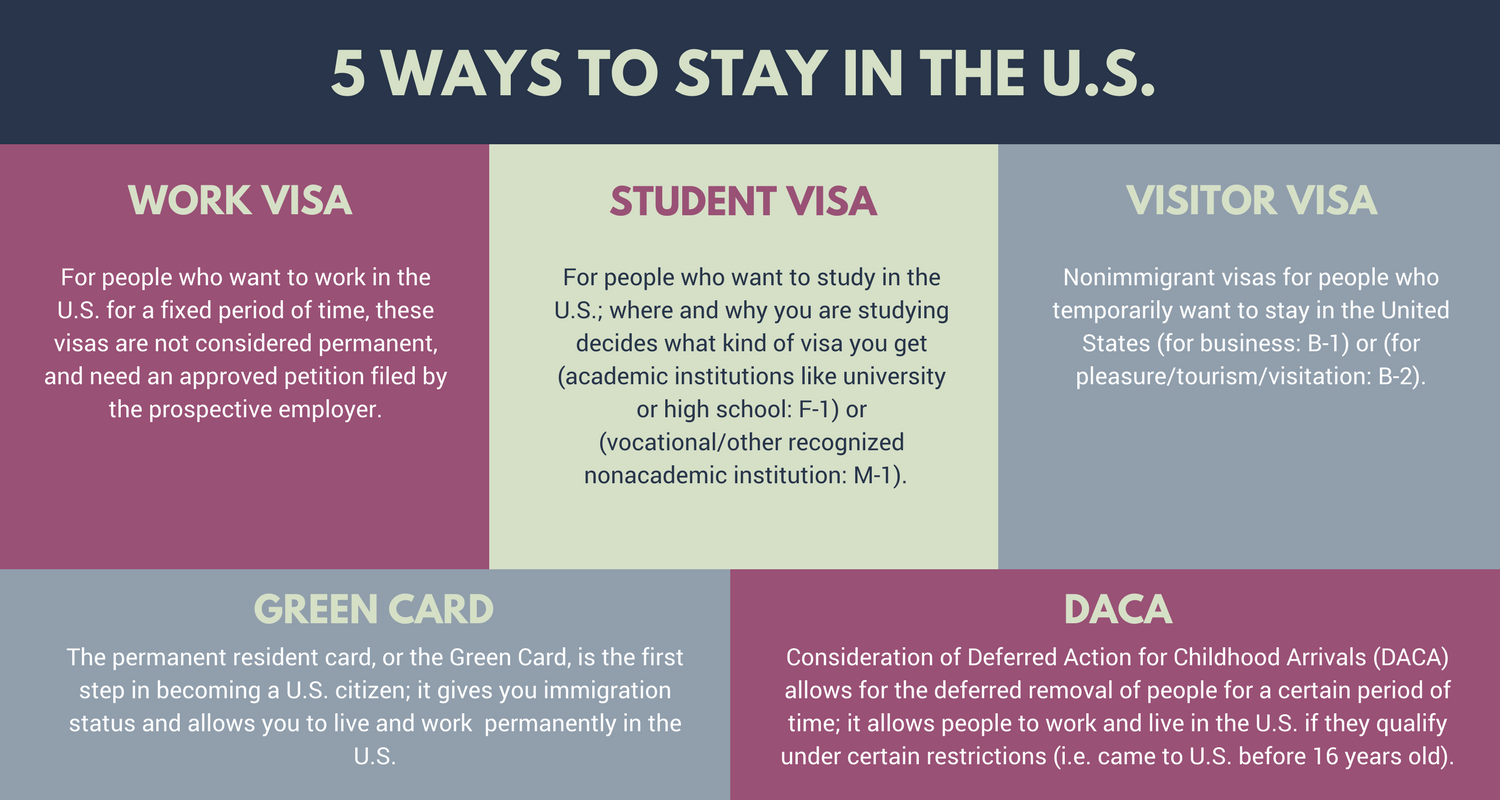

Over the past seven weeks, Trump’s focus on anti-immigration has sparked national outcry, with several democratic senators pledging to block funding for the wall and the Ninth Circuit court ruling Trump’s travel ban on seven countries unconstitutional. Despite the national pushback against these policies, many visitors to the USCIS expressed indifference towards them. Sri Lankan immigrant Revantha Thanuwara recognized radical immigration reform had potential, but wasn’t very interested in the details. Thanuwara believes Sri Lankan immigrants pose little threat to the U.S., and doesn’t believe any immigration policies would directly affect him. “I think it’s a slippery slope, he can offend a lot of people very easily,” Thanuwara said. “I think if whatever policies he makes he’s thought about it hard and through, it’ll be fine. I try not to follow it too much.” Thanuwara’s narrative was common among visitors to the USCIS – many people understood the changes that Trump was making in the White House, but few felt the impact or believed that it would affect them due to their economic status or country of origin. Samaresh Nair, an immigrant from India, came to the U.S. 16 years ago as a student, before getting a job in the Bay Area. Nair, like many other Bay Area residents, is one of many Asian immigrants who moved to the region in the early 2000s. But despite Nair’s long residency, it’s taken him over a decade to receive his citizenship. “I don’t necessarily agree or disagree with [his policies], it just depends on how you look at it,” Nair said. “If I was on a student visa, or an H1 or something, it could have possibly affected my citizenship. But it probably won’t affect me.”

Nair was not worried about the Trump administration’s vetting, but Nigerian immigrant Paul Awuzie was less nonchalant. After living in the Bay Area for over two decades, Awuzie had come to the USCIS to complete his wife Lilian’s citizenship application, and could empathize with the need to protect national security. “I have nothing against the idea of trying to protect Americans from insecurity from terrorists and all that,” Awuzie said. “The thing about [the ban] is: something that affects one person affects us all. Today it is the Muslim religion, tomorrow it could be something else, so we would begin to stand against stereotyping, grouping of people. We don’t know what the future will be like.”

As of now, most visitors to the USCIS feel safe. But Judith Camacho, a 21-year-old Mexican immigrant who moved here when she was nine years old, faces the direct effect of Trump’s immigration policies. Camacho’s residency in the U.S. is protected under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Act (DACA), a federal initiative allowing child immigrants a delay on their removal from the country. Camacho’s DACA permit must be renewed every two years for her to work legally, but according to CNN, the program itself could be modified under the Trump administration. “I already have goals that I want to achieve, and [with Trump] taking that away, it’s basically taking everything away from us,” said Camacho. “It’s been really really hard to stay positive throughout this whole thing that’s going on, especially because I love my job and if I can’t get my work permit anymore, then I can no longer work where I want to work.” If Trump’s anti-immigration policies become too severe, immigrants like Camacho will be forced to pack their bags and leave. But for individuals like Jain who have struggled for years to finally become citizens, they are hopeful that the United States will remain home. “You get a job, you get another job, then you say okay, maybe a few years,” Jain said. “And then you have a family, then kids grow up here, kids start going to school and then it becomes impossible to go back.” He laughs. “That’s pretty much the story of every immigrant,” Jain said.