here was Manuel Bedrossian, her AP Calculus student at Glendale High School. She had approached him after the AP test, asking about his college plans, and Bedrossian told her he wasn’t going to college because he already knew he was going to be a mechanic, just like his father and his brother were, and still are today. And when the school year ended, she remembered feeling overjoyed when she learned he had taken her advice and was going to junior college to pursue what he loved. She felt that maybe, just maybe, she had changed his perspective.

here was Manuel Bedrossian, her AP Calculus student at Glendale High School. She had approached him after the AP test, asking about his college plans, and Bedrossian told her he wasn’t going to college because he already knew he was going to be a mechanic, just like his father and his brother were, and still are today. And when the school year ended, she remembered feeling overjoyed when she learned he had taken her advice and was going to junior college to pursue what he loved. She felt that maybe, just maybe, she had changed his perspective.

For math teacher Katie Collins, it’s these memories of the kids that she taught in the urban Los Angeles area that stuck with her the most.

Most clearly, she remembered the email Bedrossian sent her eight years after his high school graduation, thanking her for being one of the first people to believe in him, and letting her know that he had gotten accepted into the California Institute of Technology’s Ph.D. program. Tears had streamed down her face when she read that email, and they flowed again when she showed it to her husband and her parents.

In the email, he said that Collins was one of the only people to point out the possibility of a different direction. He also told her that her Calculus class was the first time that he had felt challenged at school.

“It was the first time school had ever been challenging for him, which I thought was really interesting,” Collins said. “That a child can go through an education system and not be challenged once until you’re 18-years-old.”

Collins grew up in Cupertino — when the tech boom began in the 1980s. When she went to MVHS as a student, the school had a full computer lab of bulky, heavy desktop computers, which was uncommon in the rest of the nation at the time. She thought it was normal, but when she went to college, she found out that many of her peers had only had access to a few computers in high school. After graduating from MVHS and Occidental College, Collins took up teaching jobs in the Los Angeles area. Walking into her first job, before she taught at Glendale, she was shocked by the conditions she found. She spent her time there teaching in a dilapidated portable, lacking many resources from the school for the kids. She remembers soliciting the barbershops and hair salons for their leftover magazines and making runs to Goodwill to pick up any books she could find so her students would have something to read. It was a staggering contrast from what she had experienced in her own education. Very few students had pencils, and there were no overhead projectors in the room that Collins taught in.

“Those are just things you sort of expect, the behind-the-scenes stuff,” Collins said. “The fact that I do have an ELMO [projector]. The fact that I just literally open my mouth for 30 seconds to Ms. Scott and then magically 30 Chromebooks appear. I think that that definitely changes the education for you guys. I think it changes what you’re capable of accessing.”

Principal April Scott explained the method behind the seemingly instant appearances of the laptops. The district gives our school tech-matching dollars, where they will pay for two thirds of the technology purchased up to a certain cost. Our school itself has also saved up a fund for technology from its school site budget, which allows us to buy more Chromebooks. When teachers send a request asking for a cart, she checks in on how they would use it, then sends in a request for one. She’s noted that many teachers use their carts frequently, and she likes to be able to provide these resources.

“My goal as the principal is to provide [the teachers with] as many things as possible to make their lives better so that students can learn,” Scott said. “We try to throw in as few roadblocks as possible and really say ‘yes’ significantly more than we say ‘no.’”

Back when she was teaching in Los Angeles, Collins had tried to provide the resources she could by buying the supplies herself, but she remembers realizing there was a bigger issue beyond the lack of raw materials in class. It wasn’t just about the physical classroom resources, but the resources kids received at home. With other worries such as paying the bills or being uncertain where they were going to sleep the next night, she thinks families in the area had other concerns on their mind besides their children’s education.

They never really had access to just the basic academic equalizers,” Collins said. “Even things like food. Do you have food in your belly every day to be able to sit there and concentrate and try to learn? And a lot of those kids might not have. These are things sometimes we forget are part of education.”

During the interview, Collins discussed the difference between her MVHS and Glendale students. In the Cupertino area, most students are either planning on taking some form of Calculus either in high school or in their early college years. At Glendale, she had one tiny class of students.

“I want to be clear, it’s not bad to have money, because people work hard for the money that they earn,” Collins said. “But I do think that it is a skewed perspective sometimes in terms of education.”

Collins surmised that if she had two kids, it would cost around $120,000 per year to stay in Cupertino.

A DIFFERENT PATH

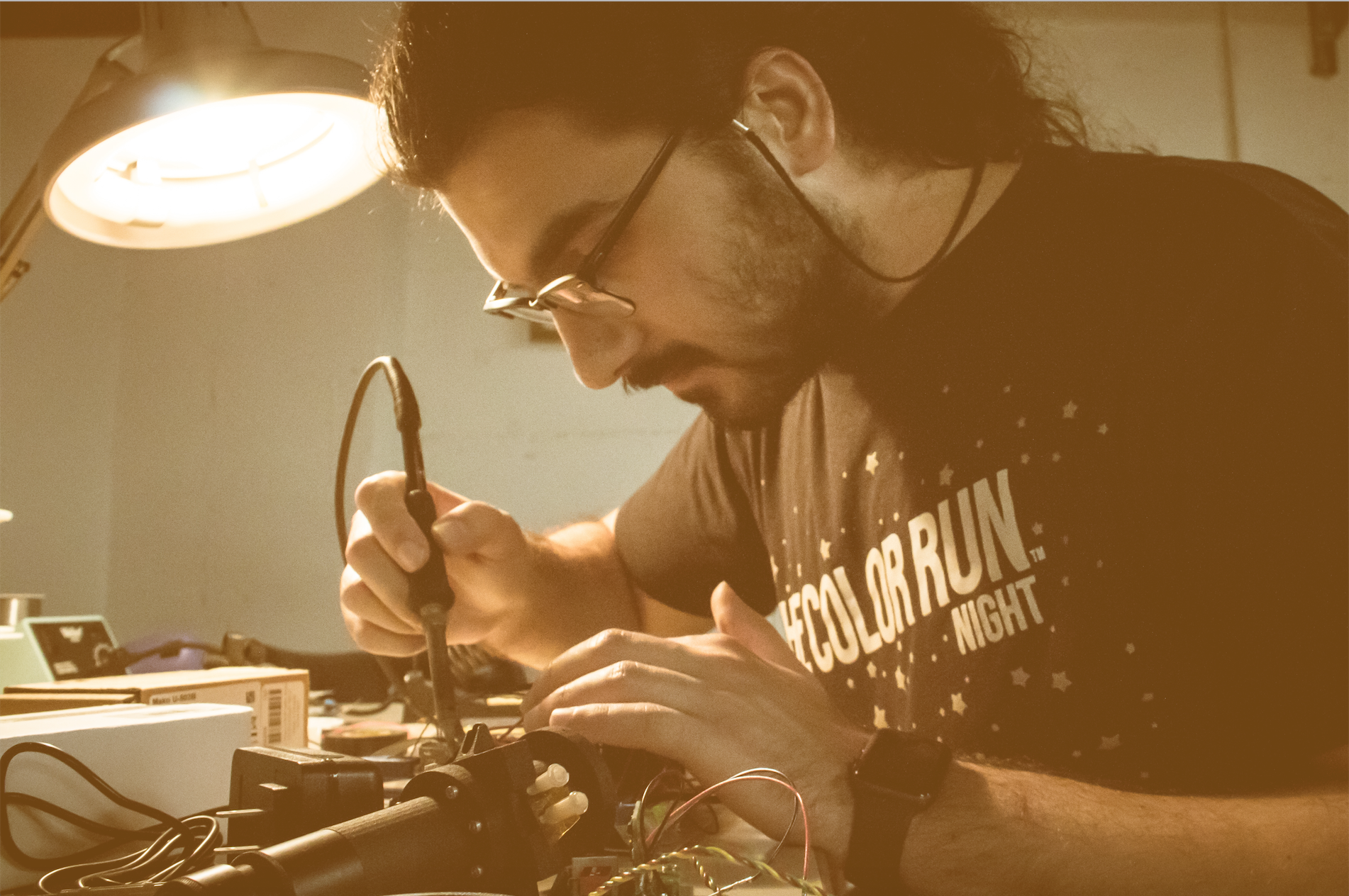

Manuel Bedrossian, now 26, vividly remembers his conversation with Collins back at Glendale High School in 2009. Collins, who at the time went by Ms. Williams, had pulled him aside after he had taken the AP test for Calculus and gotten a 5. She had inquired about his plans for the future, for college. He had a job as a mechanic at the time and told her that he wasn’t going to college because he already had this job. He remembers Collins told him that if he liked math, he should look into engineering because he had such a gift with the subject and could combine it with his love for working with his hands. It was because of her encouragement along with that of a few others that he decided to pursue higher education at all.

Bedrossian had been considering pursuing something different than his parents, a career that required higher education, but he didn’t really know how he would do that. Talking with Collins helped boost his confidence that he could make it happen.

The encounter stuck with him so much that years later, in 2016, he wrote her an email. He had just been accepted into the California Institute of Technology’s Ph.D. program for Medical Engineering. He wanted her to know the impact that she had on his decision, and to thank her for believing in him.

He said that he doesn’t believe in luck. Instead, Bedrossian likes to see things as “a convergence of opportunity and preparedness,” which is how he views his path to the California Institute of Technology.

His preparation, although he did not know it at the time, began when he left high school and started going to community college. After finishing his GED, he applied to multiple four-year universities, and was accepted into UC Riverside.

While working towards his GED, he was also continuing to work as a mechanic to cover the basic costs of living, which proved to be a challenge.

“You have to make money because you have to eat, but the more time you spend working, the less time you spend on class, so your GPA suffers,” Bedrossian said. “When your GPA suffers, then the possibilities of school that you can attend just decrease almost exponentially.”

The balancing act’s difficulty was heightened by his consciousness of the finite time in each day.

“There’s only so much time, and the more time you have to spend thinking about financial stuff, the less time you spend preparing yourself for the future,” Bedrossian said. “And so it’s a battle between short-term and long-term goals and it’s a very hard balance to find if you’re struggling.”

In his second year at community college, Bedrossian began working as a research technician at the California Institute of Technology, coincidentally for the person who would later become his Ph.D. professor. And that’s where the opportunity aspect of Bedrossian’s non-luck philosophy comes in.

The position became permanent, and he continued working there while going to UC Riverside. Then, he took a gap year to work at the Institute researching into creating a holographic microscope. He continued eagerly working through the summer, until it became his Ph.D. project. When it came time to apply to graduate schools to continue his research, it seemed like an obvious decision to apply to the California Institute of Technology for his Ph.D., but he also applied to other schools.

However, Bedrossian thinks that lots of schools judged him more from his socioeconomic status.

“[There was] a socio-economic barrier that I had to overcome,” he said, “And I often felt like I had to outperform my cohorts in order to make up for that.”

As a kid in Collins’ calculus class and in his more formative years of education, Bedrossian admits he never thought much of school. He just saw it as “something to get through,” never as a career, as a job. But, he says, Collins changed his mind. And now, thanks to her encouragement, he has done exactly that: made learning into a job, pursuing his Ph.D.

A NEW ENVIRONMENT

Stepping into her science class on her first day at MVHS, she was astounded by what she saw. The amount of equipment that lined the walls for her to use for her classes, for exploration, was unlike what she’d experienced in her education before.

Moving to the United States from India was just another change for junior Shivika Sivakumar. She’d lived in many different places in India before, so relocating wasn’t new to her. But there were some larger differences that came with a change in country, especially moving to a more affluent area like Cupertino. She’d lived in Bangalore before, which is often called the “Silicon Valley of India,” so she didn’t see many differences between the two. But there were a few little things that struck her as different between the two.

“I’m being exposed to all of these different things that I never would have been [otherwise],” Sivakumar said. “An example would be in a normal classroom, using all of [that] scientific equipment and all that. So maybe, I could’ve done that in Ph.D. or in a graduate school [in India].”

She feels that a lot of her peers take these resources for granted, things like the black box and the darkroom that here, people might be used to having, but she didn’t have. There was a difference in what people expected, too. In India, school stress was a given. Everyone knew, for example, 10th graders would be stressed due to the workload, but it was never boasted about. Similarly, staying up late was frowned upon.

“Over there, if you sleep at four [a.m.], it’s kind of bad,” Sivakumar said. “It’s kind of like you’re [not] smart, because you’re not sleeping.”

She wasn’t really sure where to start when defining the cost of living in Cupertino.

“A lot. I’m not sure.”

A FOREVER HOME

She sees students walking around the neighborhood, hunched over from the weight of their backpacks and lugging themselves over to tutoring places as a common scene. The sidewalks of De Anza Boulevard and Stevens Creek Boulevard always hosted a legion of students; everyone always seemed like they were doing something academic.

To junior Hima Tammineni, who has lived in Cupertino her entire life, words that Cupertino evoke are ones that are often used by others: academic and sheltered. She notes that although the academic stress most face in Cupertino is starkly different from the stress of having to earn enough money to put food on the table every night, it is still grounded.

“We do have a lot of pressure coming from certain places but it’s not life or death for us so we should definitely take it a little less seriously,” Tammineni said. “I mean, enough so that we don’t end up in a place where we’re stressed to put enough food on the table, but it’s very different.”

She added that there’s not much visible poverty in Cupertino, and roughly estimated that it costs hundreds of thousands per year more to live here than in other similar cities around the world.

Bedrossian still thinks about how much his attitude towards education has changed, and how he wishes that all kids could escape poverty. And he thinks that education is the way to give more opportunity to others.

“Education is the only long-term solution to poverty…” Bedrossian said. “I didn’t necessarily grow up in poverty.I was just on the low end of the spectrum in terms of middle-class, but it is the long-term solution. Getting to that is very difficult, but I think it’s worth it.”