hen her dad came back from China, junior Victoria Xiao was met with a lot of questions. Her cousin, just a grade younger, lived a completely different life in China, one of speech and debate tournaments, math and science contests.

Why can’t you get this problem? Why can’t you understand this?

What have you been doing with your life?

Xiao’s tanned skin, her brown, almond shaped eyes and her frizzy black hair seemed foreign on her body. Her identity as a Chinese-American was blurry, the lines of Chinese characters she wrote week after week at Chinese school, the food that she ate at each family gathering.

“So that to me, I felt like to be a good Asian child was to be good at math and science, and to have done all these competitions,” Xiao said, “but I felt like that wasn’t my definition of success.”

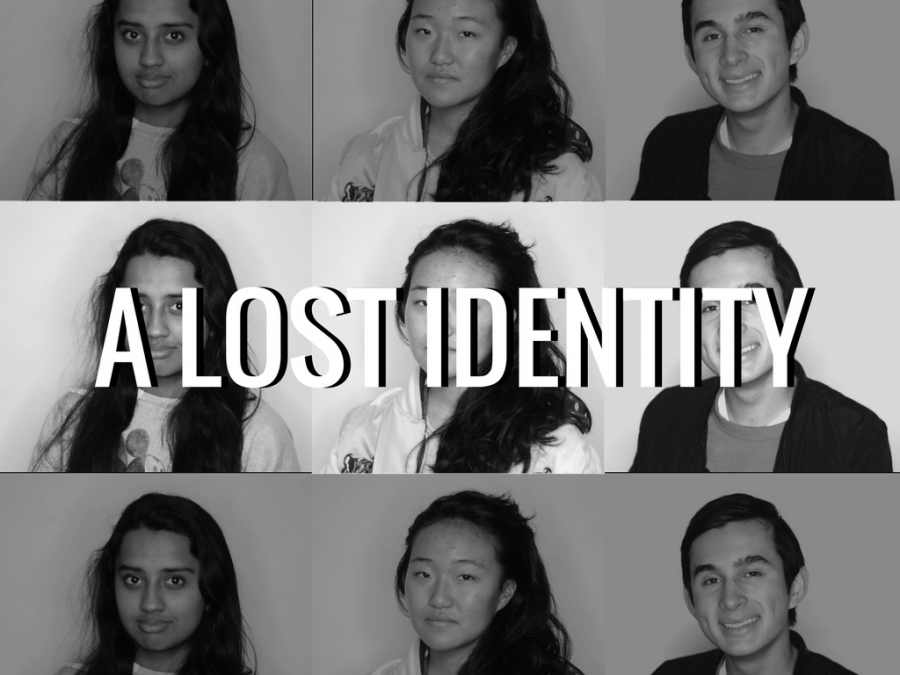

From the moment we enter this world, the environments we’re exposed to and the people we meet all play a significant role in shaping our identities. Over time, these identities may change as we grow, and possibly become lost along the way. For Xiao, senior Michael Burgess and junior Mritthika Harish, that process has allowed them to further gain a sense of self.

Childhood memories

Burgess was around 7-years-old when he first began to feel conscious about his biracial identity. At a family gathering with his Asian side of the family, he had said something in Chinese. To him, speaking Chinese was nothing special, considering how he grew up speaking three languages.

But to his Chinese relatives around him, it was quite the opposite.

“The kids were like ‘Woah, this white person speaks Chinese, like wow,’” Burgess said. “As a kid I hadn’t really thought of [race differences] that much and… how it might differ from other people’s experiences.”

Burgess attributes this to the power a community has to shape the identity that someone has, and for Harish, that was exactly the case.

Harish spent her childhood between being a minority in North Carolina, then a part of the majority in Cupertino. In Cary, NC, she was one of the only Indian kids in her class, and because of that she became hyper-aware of people’s judgements the way she looked, the way she spoke. Even the food she ate.

For something as simple as a school lunch, her parents renamed the familiar soft and savory Dosa as “smaller sweeter pancakes” to encourage her to take Indian food.

“‘What if people ask me [about my food]?’,” Harish said. “Like I’d always tell [my parents] that and that went on like even after I moved [to Cupertino].”

Finding a sense of self

It was the Fourth of July, Xiao recalled. The bursts of red and blue could be seen from the windows of the plane, and the pilot warned everyone to remain seated.

But one Chinese family ran frantically around the plane, trying to look out the window and marvel at the sight.

“I was like ‘oh god’,” Xiao said. “Like part of me felt that they were ruining some kind of [Chinese] reputation, and I know it’s really stupid but a little part of me felt didn’t want to be associated with that kind of image.”

She felt as though there was a stereotypical view of what a Chinese family looked like, and she wanted to prove that she and her family weren’t like that. In the short stories that Xiao wrote for fun when she was younger, the heroines would be white and she would particularly give them white last names. Although it seemed unintentional at the time, Xiao looks back on it as a reflection of what she aspired to be, her dream self.

“I wanted to be white, that’s the thing,” Xiao said. “I wanted to be white because it was easier and you fit societal norms of beauty.”

In a similar sense, Harish remembers being called “whitewashed” after moving back from North Carolina. She had tried so hard to blend in with the predominantly white community there, but after moving to Silicon Valley she was still perceived differently, regardless of the people she was surrounded by.

“The way that they say the [whitewashed], it’s like they’re giving you a race,” Harish said. “Like ‘oh you’re Indian but you’re not Indian, oh… if I give you Indian clothes you wouldn’t know how to put them on’.”

That way of placing labels on someone is what Burgess sees happening because he’s biracial. With receiving questions like “are you more white or more Asian” or “if you had to choose one…” it becomes difficult to communicate his identity to others.

“People have the urge to categorize and I just want to be myself,” Burgess said. “Like why do I have to be more of one than the other… that’s not how I was created.”

Accepting the reality

As Harish found a group of friends that she could connect to, she saw how she could be herself in every aspect as long as she had the right community.

“I might as well just embrace who I am because I can’t change it, and being someone I’m not isn’t going to help me, isn’t going to help my family,” Harish said. “It’s going to end up hurting them and the last thing I’d want to do is hurt anyone.”

Burgess has also been able to accept being half Chinese and half white through accepting other people’s judgements and making sure that they don’t change how he sees himself.

“As I’ve grown older I’ve been able to value both sides [of my identity], and yeah I’ve definitely come to terms with it and I embrace it,” Burgess said. “It’s what makes me unique and special.”

For Xiao, the Chinese-American identity that she felt she couldn’t fully connect with was slowly making more sense. She began to read books like the “Joy Luck Club” and “Bitter Melon” with characters that she related to, rather than those that she aspired to be because of their acceptance in the mainstream media. She was able to connect with people from outside the Bay Area through a program called the Mosaic Project, which brings together children from all kinds of diverse backgrounds to empower and educate them on their community.

She didn’t have to be the girl with red hair and green eyes, she didn’t have to have a white last name, she didn’t have to be paler.

She was happy with being Victoria Xiao, the Asian-American girl who’s passionate about being a social worker in the future, who loves feminism and who wants to make a difference.

“I was like ‘hell yeah!’, I’m Asian-American and I have a voice that is different and I can use it as a benefit that allows me to connect with other people,” Xiao said. “I know for a lot people it doesn’t come as sudden as that, but I did and I’m really lucky that it did [for me].”