or 18 years, Brian Wilson taught in the same classroom of the same school in Michigan. Then, three years ago, 30 teachers in his district were laid off, four in his building alone. Policies had been gradually shifting, adding mandated paperwork onto teachers’ already busy schedules. Conversations between his colleagues strayed from discussing teaching strategies to reminding each other to fill out required paperwork. Friends around him were eager to leave behind their teaching days and started a constant countdown. Twelve more years until retirement. Ten more years. Eight more years. Five more years.

Wilson hated those conversations – the paperwork didn’t make him a better teacher and counting down the years until he retired just wasn’t fun. He knew it was time for a change and the only options were to teach in a different state or to switch careers. And when a friend told him a job was available in California at Palo Alto High School, he took the chance and applied.

On Nov. 23, President elect Donald Trump selected Betsy DeVos as his pick for Secretary of Education. She was a prominent figure in Michigan politics, having served as the chairwoman of Michigan’s Republican Party. But in many eyes, she wasn’t the ideal person for the position.

“To have someone in that position who has never attended a public school, never sent a child to a public school, who has really rallied towards trying to destroy the public school — I know having someone who believes that, in that position, can’t be good, but I don’t know how much damage could possibly be done,” Wilson said.

Five years ago, Wilson was one of the many teachers in Michigan who watched skeptically as legislature began placing a stronger emphasis on accountability in the classroom. More teacher evaluations followed and teacher-administration relationships became tense. Public schools began to close, inclining students to join charter schools. In his eyes, public education itself was changing, and not for the better.

Today, Wilson is halfway through his second year at PAHS, a school that is in what he refers to as an “exceptional” community, whereas in Michigan he worked in a lower working middle-class community. Although he acknowledges that the school he teaches at now is in no way representative of the rest of California’s, there are still many notable differences between California and Michigan — one of the largest being the different way teachers in the two states perceive charter schools.

Wilson has sensed an understanding among Californians that both charter schools and public schools have their own separate purpose and that more importantly, the two can coexist. In Michigan, that wasn’t the case.

“I think in Michigan, if you’re a public school teacher and you’re a member of the union, you’d have a real hard time with seeing any value in the charter school system in Michigan,” Wilton said. “Because it just appears very clear that there’s a goal of… putting everyone into some sort of charter environment where the kids who can afford it are going to decent schools and the kids who aren’t are just kind of out of luck.”

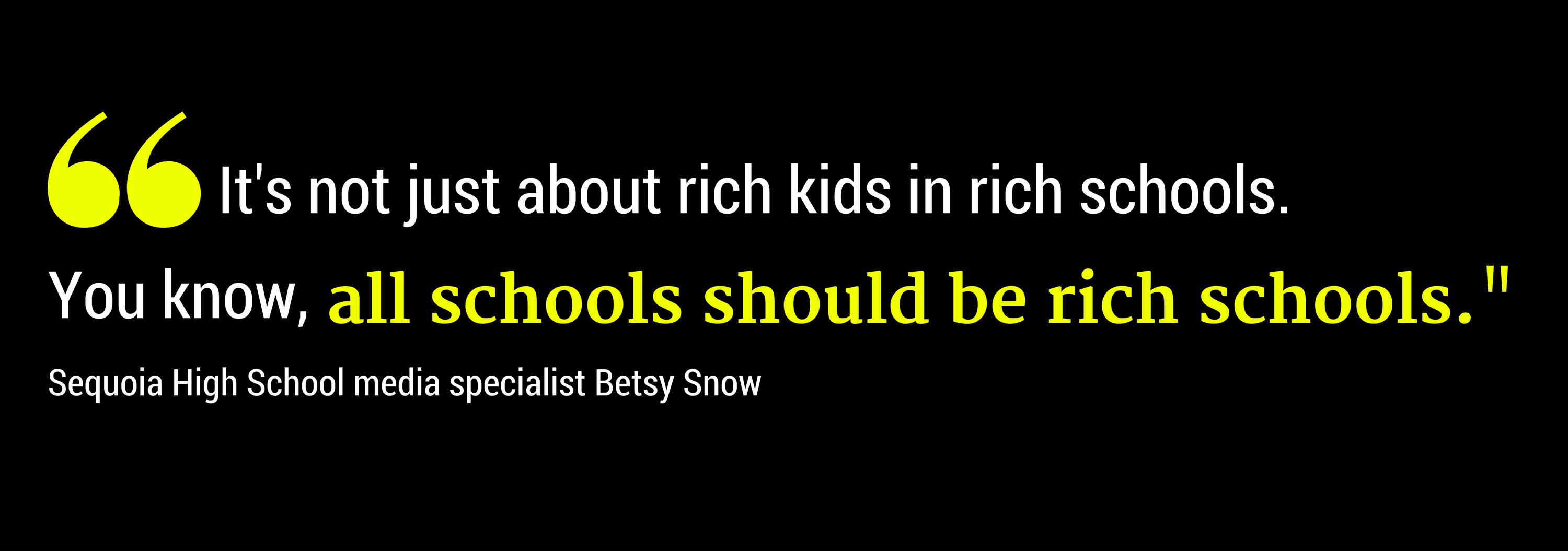

Betsy Snow never taught in Michigan, but received her training to be a teacher there and is now a media specialist at Sequoia High School. Like Wilson, she also harbors similar reserves, saying that a basic education shouldn’t have any connection with a family’s financial status.

Wilson has had friends that taught in charter schools, but he says they haven’t lasted long for financial reasons. The pay for a public school teacher might be low, but the pay for a charter school teacher is lower. According to Michigan Capitol Confidential, the average salary for a charter school teacher in Michigan during the 2011-12 school year at $42,864 was $20,000 lower than that of a public school teacher, who earned $63, 094 on average. That lower income, along with the fact that most charter schools aren’t unionized makes teaching at a charter school in Michigan a less than ideal job for someone hoping to raise a family or buy a house.

Yet from a student point of view, the perceptions are different, as junior Mritthika Harish knows. Harish went to Fuller Magnet Elementary school in North Carolina. A magnet school is another type of school that is similar to a charter school in that it is also an independently operated public school that can be started by for-profit companies or other individuals. Even though she was only at the school for half a year, the more hands-on learning environment where teachers were more involved at that school in particular makes it her favorite school to this day.

“I don’t think that where the money goes should [have an] impact as long as your child or your loved one is getting the education that they need,” Harish said.

However, despite the difference between the teaching style in the two, Harish considers both a conventional public school education and a charter school education to be equally viable in teaching the students effectively.

In Wilson’s experience, teachers got along regardless of what school system they taught in. Teachers’ incomes are an issue that teachers here in California face as well, yet in Michigan the two school systems themselves seemed to be in conflict, with what Wilson refers to as“the specter of charter schools” looming over public school teachers, this sense that the livelihood of public schools is being threatened by charter schools supported by wealthy politicians looking for money.

Wilson watched firsthand as Michigan’s education system shifted over the years, deteriorating in part because of the emphasis on charter schools that DeVos supports. Over the years he couldn’t help but feel that there were politicians and business leaders who were out to dismantle the public education system. And as a teacher who taught in Michigan for most of his teaching career, other teachers from California often look to him for an explanation and expertise on DeVos. There’s a certain association between him and DeVos that he can’t quite escape, simply because he’s from Michigan. But it’s not a sense of guilt, it’s more of a sense of disbelief that she came from Michigan.

“I almost feel apologetic … teachers in [PAHS] would come up to me like ‘what’s the deal with this DeVos person?’ like I was somehow sort of responsible for it because I’m from Michigan, which is silly,” Wilson said. “There’s a certain level of like – not feeling culpable for it – but like, ‘what have we unleashed here?’”

PAHS and MVHS are schools where teachers are in little danger of losing their job. Yet, in past years, as schools closed and funding dropped, some of Michigan’s teachers were put on the chopping block. Wilson didn’t feel like he specifically was at the risk of losing his job, but he knew many of those around him felt like they were. But the impact of the annual layoffs still affected him, creating an irreversible rift between the administration and teachers.

“Every year, administrators would be put in the position where they would have to make decisions to let teachers go,” Wilson said. “And when that condition exists I think it’s really hard for a principal and staff to be buddies and be on the same page… that becomes very hard because they know it’s gonna get to March or April and [then it’ll be like] ‘I have to fire 6 of these people so I can’t become close with them.’”

And Snow agrees that what will actually happen with DeVos at the helm of the country’s public education is yet to be determined. And rather than waiting for an enormous change that may never happen, the teachers will simply continue to fulfill their own duties as teachers — to help the students learn.

“I think we’re all conscious of what’s happening and yet there’s a lot of unspoken agreement that we’re going to hunker down, focus on what’s in front of us — the day to day… the fact that kids have assignments to write and they have essays to write, and they need support right now,” Snow said.

Public or charter school, Michigan or California, DeVos or not, the definition of education remains a constant. Wilson and Snow are just a few teachers among many that will always continue following that definition, guiding their students towards the best education possible.