Co-authored by Nanda Nayak

It’s not uncommon to see name after name of MVHS students on lists of science competition winners. But with those countless science experiments conducted comes the long list of materials used for research. Commonly seen items may include pipettes or centrifuges, objects that most science classrooms contain and that most students have used before.

But what about artificial skin grafts, thermoelectric generators and drosophila flies? For three students, these materials are what their projects and research depend on.

hile an artificial skin graft sounds like something used to create Frankenstein, senior Bhavana Pabbisetti has other ideas in mind.

Pabbisetti, in her attempts to create an adhesive patch to deliver thyroid medication, needed a life-like model of the human skin to test her medication on. So, she got an artificial skin graft.

“It looks like a silicone sheet with a net on top and it represents the epidermis and the dermis. I just stitched them together,” Pabbisetti said. “I actually bought the membrane online for around $100 and I just found a net at Home Depot.”

In the beginning, she had expected the skin graft to be far more interesting than it appeared to be, but she was soon able to come to terms with the functionality of the product.

While Pabbisetti may have been disappointed with the way her skin graft looked, she still appreciated its productivity. Most of her parents and friends have opposite opinions.

“[My friends] were really surprised and kind of terrified that I have random membranes laying around in my house,” Pabisetti said with a laugh. “They were like, ‘Do you also have a dead body there?’”

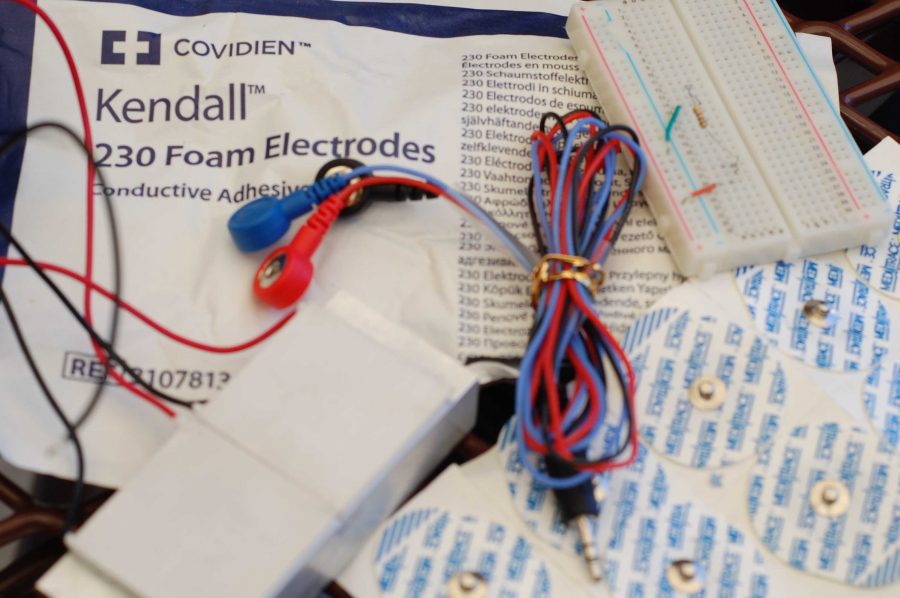

It started with a project on thermoelectric energy. Sophomore Priscilla Siow was researching the ability to charge heart rate monitors by converting heat into usable energy when she acquired a collection of colorful cables, breadboards, foam electrodes and peltier tiles.

For her project, she used the peltier tiles as a thermoelectric generator.

“You put heat on and the other side is cold, so the temperature differential excites electrons which creates an electric current,” Siow said motioning towards the peltier tiles, “and I connected this to the heart rate monitor.”

After submitting the completed project to the Synopsys Science Fair and winning second place, she no longer has a use for the materials, and they remain in a pile sitting in her room. Although she doesn’t have much use for them right now, she believes she may find use for them again if the project was continued.

“I was thinking of doing another project next year and it can be engineering based again so I can use these again, but honestly, I have no idea [what to use them for],” Siow said. “You can’t use it for recreational use.”

Siow finds that with biology related projects, it’s easier to get rid of excess materials since most things, like plants, can simply be disposed. As for her collection of wires, electrodes and generators, they have a place in her room until the future rekindles her interest in science.

To some, fruit flies are nothing more than an annoyance. But to freshman Vivek Kamarshi, drosophila flies were a major component in his science experiment.

Kamarshi conducted a project in an attempt to understand whether fruit flies could get a fever, and infected them with a fungus. He found that their body temperature increased when they were infected, and their body temperature decreased whenever they weren’t infected.

“It’s just like when humans have a fever,” Kamarshi said. “But because flies are cold-blooded, they need to go towards cooler temperatures.”

As to why he chose to experiment with fruit flies, Kamarshi’s reasoning is simple.

“The genome of flies is a lot simpler, especially [since the flies] have four chromosomes,” Kamarshi said. “So scientists mapped it very early on and know what each part codes for a certain protein.”

And while it seems like fruit flies are abundant everywhere, Kamarshi had to order them from a specific association, and contacted professors who previously worked with fruit flies to obtain them.

And while it seems like fruit flies are abundant everywhere, Kamarshi had to order them from a specific association, and contacted professors who previously worked with fruit flies to obtain them.

“There are online resources but mostly you have to order through an academic institution,” Kamarshi said. “I contacted professors who work with them.”

Experimenting with flies may scare some people away, but for Kamarshi, the common household pests played a significant role in developing and completing his research.