Story co-written by Sandhya Kannan.

If not the high scoring students and the plethora of tea joints scattered across the town, Cupertino prides itself on one thing: ethnic diversity along with its cultural integration into a “white” society.

And yes, it is true that we have achieved a very unique status as a melting-pot of a town— we are one of the few across the nation that can say it has a higher percentage of minority groups than Caucasians. Multiple ethnic groups coexist and contribute to the greater productivity of the Silicon Valley metropolis, something that is rightly credited to immigrant parents and grandparents who moved here from other regions and nations over time. As a result, it has turned the once predominantly-white and agriculture-based Cupertino and Cupertino-like cities into stews of culture, progress, and innovation.

At Monta Vista we have adopted the identity of being a school of minorities now in the majority. Many of us speak of traditional Asian ideals preached by elders regarding ethics and hard-work, and attempt to integrate it with the American identity of achieving our own personalized “American Dream,” which often leads to several early-onset identity crises. In these periods of intense introspection and connection of ideologies, newly established generations often grow up bonding with one another and establishing their identities in a relatively facilitated manner. For kids who move here in the middle of their teenage years, however, the transition is anything but easy.

Monta Vista is not as integrative as we make it out to be. Anyone who walks into the cafeteria during lunch can see that a few rows of tables in the back are occupied solely by ELD or international students. Between students who have lived here their entire lives and those who have freshly moved in, there is always some visible divide to be seen— specifically between the “native” and international students.

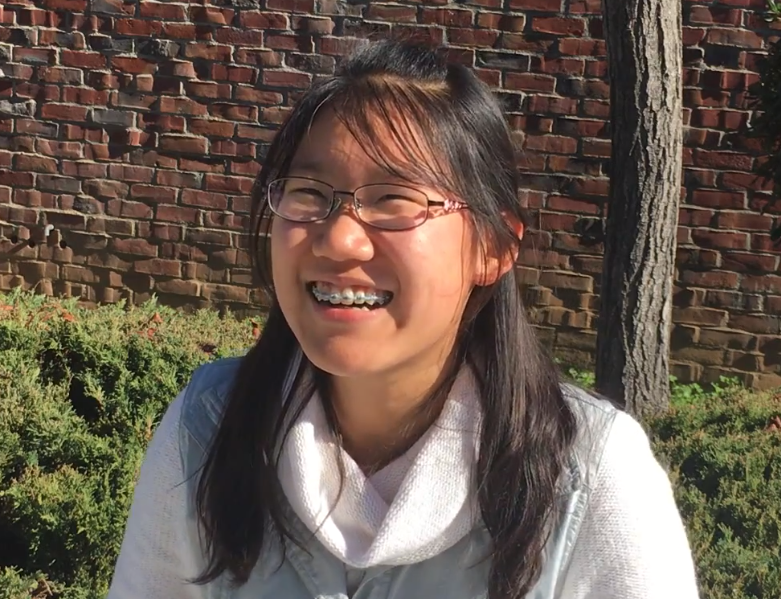

Freshman Elisa Xu, an ELD student who moved from China to the US for high school, reflects upon her hard time adjusting to the English language and interacting with native speakers.

“I kind of feel uncomfortable around [non-ELD students],” Xu said. “I think others look at me like I’m a stranger.”

While she agrees that she doesn’t feel at ease around native English speakers, she believes that it is very helpful when she does get the chance to interact with non-ELD students, as it helps her English communication skills.

We often blame the divide on the language barrier, but that’s an oversimplification of the problem. Although it is true that broken fluency in English can contribute to difficulty developing connections with other students, friendship and acceptance go both ways. It is arguable that currently, the most we as native students are offering is tolerance — not necessarily active measures taken to accept and integrate.

ELD students find common ground among each other, and though they come from a range of countries, they are unified by the same language barrier. Sophomore Kiarash Ghaderi, an ELD student who has lived here for two years and is now enrolled in ELD 3, has formed relationships with ELD students from different backgrounds.

“At first it was hard, but after a few months, it was okay because I adopted to the culture and English and I had some other English classes to help me learn English,” Ghaderi said. “Being in ELD classes helped me a lot to learn English, and being friends with other people from other countries helped a lot because we have to speak English.

It’s evident that ELD students feel more comfortable reaching out to fellow ELD students, and that’s completely normal. But when that translates into them feeling uncomfortable interacting with native speakers, the native students need to take the initiative.

The New Student Support Club offers assistance to any newcomers to MVHS, which is unquestionably helpful to the adjustment process that new students must experience, but consider the fact that there are no clubs or student-run organizations on campus specifically to aid international students in interacting and building relationships with American-born students. Apart from the occasional Link presentations and class-time opportunities after graduation from sheltered classes, ELD students are effectively left alone in the open to initiate their own interactions with peers. Having established that many of these students are already uncomfortable enough with the new language and culture, that interaction is rarely initiated successfully.

Instead of recognizing this butterfly reaction of events supplying the divide, its reason is often blamed on laziness on the part of the ELD students in trying to learn the culture and language. Although this may be true in some cases, the ironic reality is that American-born students do exactly the same thing in many cases. We often fail to understand the difficulty they may be facing in integrating their cultural identity with the “American” identity, and as a result they are pinned with pejorative terms such as “FOB,” further driving the divide.

We might even overlook international students and their capabilities, using the language or cultural disparity as an excuse not to initiate conversations with them in the cafeteria. The solution is simple: if we want unity in our community of students, we cannot just sit back and watch. All it takes is one conversation to start another, and one lunch to ignite a friendship. Let’s not let those learning opportunities and experiences pass by everyday. Just because it involves integration, doesn’t mean it’s as hard as Calculus.