or Chinese-Americans, it’s that time of the year to gather with family friends, receive red envelopes and eat an abundant dinner. Some Chinese-Americans may look forward to the event, and others reluctantly go to the party because they don’t have any other choice. Regardless of which category they belong to, one thing unites them—their ties to the rich history of China.

Crowded streets, shops and lines, people yelling into their phones, spit-stained streets, rude customer service. These are all things you probably have exp erienced if you visited China, and it truly is anything but appealing. But while that may be the case, Chinese-Americans shouldn’t let their impressions or shameful views of the culture prevent them from learning more about their native history. Maybe these offputting aspects stem from the lack of personal space that residents have, or the poverty that an immense amount of people have experienced which puts them into survival mode. Of course that’s oversimplifying the circumstances, but it’s worth putting ourselves in their shoes.

erienced if you visited China, and it truly is anything but appealing. But while that may be the case, Chinese-Americans shouldn’t let their impressions or shameful views of the culture prevent them from learning more about their native history. Maybe these offputting aspects stem from the lack of personal space that residents have, or the poverty that an immense amount of people have experienced which puts them into survival mode. Of course that’s oversimplifying the circumstances, but it’s worth putting ourselves in their shoes.

Our cultural identity isn’t easy to solidify when we grow up in the middle of two completely different cultures. Identities.Mic, an online publication, analyzes the conflicted identity that an Asian-American experiences while growing up in the U.S. And this applies to all immigrants’ children.

“On the one hand, we’re encouraged to embrace American culture and shed ties to our Asian heritage,” Identities.Mic said. “On the other hand, we’re expected to maintain our ethnic identity and keep our parents’ traditions alive. Failure to live up to either set of expectations can sometimes lead to fear of rejection or ostracism — even an identity crisis of sorts.”

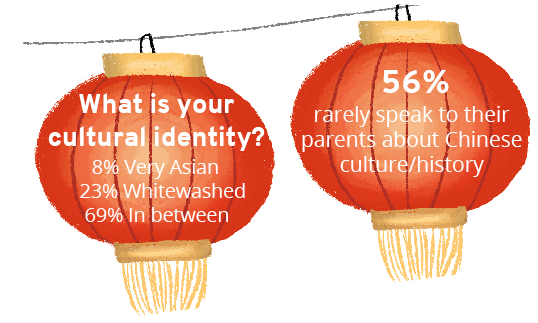

While this seems exaggerated, it carries some truth to it, and finding a place in between that makes us feel good about ourselves or even prideful is worth keeping. In a survey of 90 studen ts, 23 percent of Chinese-Americans characterized themselves as “whitewashed,” 8 percent as “very Asian” and 69 percent as falling somewhere in between. Along the way, what truly makes us feel good about ourselves is probably going to change, and we’ll experience that “identity crisis.” In the future, we are probably going to cringe at our current various behaviors—for instance, alienating our parents, hating on Chinese culture, wishing to go somewhere far away for college in escape of entrapment. But they all make up the process of discovering our cultural identity, and part of that requires open-mindedness and exploration of Chinese culture, from the influence of Confucianism to the 1.5 million people killed during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution to the significance of a rigid family structure.

ts, 23 percent of Chinese-Americans characterized themselves as “whitewashed,” 8 percent as “very Asian” and 69 percent as falling somewhere in between. Along the way, what truly makes us feel good about ourselves is probably going to change, and we’ll experience that “identity crisis.” In the future, we are probably going to cringe at our current various behaviors—for instance, alienating our parents, hating on Chinese culture, wishing to go somewhere far away for college in escape of entrapment. But they all make up the process of discovering our cultural identity, and part of that requires open-mindedness and exploration of Chinese culture, from the influence of Confucianism to the 1.5 million people killed during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution to the significance of a rigid family structure.

Fifty-six percent of Chinese-Americans stated that they rarely speak to their parents about Chinese culture or history. That’s too many missed conversations and opportunities that could’ve helped us achieve a better understanding of not only Chinese traditions but also the dynamics in our relationships with our parents. We should still acknowledge that some parents may not be very willing to share about their experiences, or that we may not find their stories interesting at all. But there’s honestly no harm in reaching out with genuine intentions.

When Chinese New Year rolls around, try initiating a discussion about traditional Chinese culture, or inquire about the legend behind the festival. Every family has its own story. Just like we believe that our parents don’t know much about who we really are, we probably don’t know much about our parents’ experiences and histories either.

There’s no right or wrong way to culturally identity ourselves. But one thing’s for sure, Chinese-Americans should be willing to go out of their comfort zone and make an effort to learn more about the 5000 years of history that extend past their limited lives.