Co-reported with Jessica Xing.

The room blazes with laughter, the smell of dumplings drifts across red walls, the television flashes with dance, fiery blues and yellows paint the night sky, the moon shines gold upon the rooftops — this has been replaced with homework and a half-occupied dinner table, unadorned walls and quiet skies. The past glows weakly behind a phone call to China and the annual television special that’s accompanied childhood.

When some students moved to the United States after growing up in China, they experienced similar changes to their Chinese New Year celebrations, but responded differently. Students discuss their once-beloved holiday: why it’s so different here, how their identities have shifted, what commercialization has brought.

Moving from Hunan to America two years ago, junior Larry Chang felt his Chinese New Year spirit drain away. He brought up school as a central cause. In China, he had two weeks to relax and travel; now, with so much work to focus on, the time and energy to celebrate has washed away. He and his friends, who also came from China some years ago, don’t talk about the New Year when it comes.

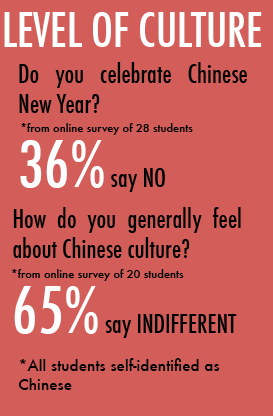

Chang felt that some Chinese in the area don’t seem all that connected to their native culture.

“Even though there are Chinese,” Chang said, “they all celebrate Christmas, not Chinese New Year.”

While Christmas calls for widespread celebration, Chang hasn’t seen Chinese New Year being honored on campus beyond his Chinese language class. He ascribed this to the power of American culture — a force that ancestry struggles to compete against.

“This is America,” Chang said, “People who come here become Americanized and celebrate American traditions, not Chinese New Year.”

Chang pointed to another reason for decreased spirit. Like other newcomers, he had to leave much of his family. His past feasts with parents, aunts, cousins became eating dumplings with only his mom and brother. With so much family missing, the mood was simply no longer the same.

“People who come here become Americanized and celebrate American traditions, not Chinese New Year.”

While Chang struggled to leave behind those 15 years that shaped his identity, he, perhaps unavoidably, began adopting American culture over the next three years. He grew more comfortable speaking English, watched videos on YouTube, which doesn’t exist in China, replaced Chinese television shows with American movies.

But he remains Chinese at heart. While open to ideas like celebrating Christmas, he has found that merging into American culture must take time. He will continue adapting to the land he now stands upon, but hopes to one day return to the home where a piece of heart calls.

Senior Edward Wang takes a break from doing homework to go out for dinner with his mom and dad. Then he turns on the television to watch CCTV’s Chinese New Year special. It certainly doesn’t compare to the celebrations he had back in China, but Wang doesn’t complain. After all, he already had Christmas break to spend time with his parents at home and visit his family in China, and then there’s the summer to see them yet again. And that’s not all. Coming to America has introduced new wonders to him, like stuffing himself with turkey on Thanksgiving and watching fireworks on July Fourth.

Like others who moved from China, Wang noticed the Chinese New Year energy dissolve under the pressures of school and work upon coming to the United States. He pointed to the Americanization of Chinese people as another possible cause of the weaker atmosphere.

He said that Chinese New Year is personal by nature, most people celebrating inside their homes with family; yet, he still felt a chilling absence of cultural spirit in Cupertino. This was a largely intangible void created through smaller absences, like the silence that replaced the sounds of firecrackers.

“I feel like I am just a person on earth. People all need to rest, relax, celebrate holidays.*”

But even with such abrupt changes, he did not long for the past or wish for more; in fact, he preferred that organizations in Cupertino not do anything to promote Chinese New Year, despite it being so much less emphasized than what he was used to. His reasoning? Wang felt that upon entering another country — a world of exciting new cultures and practices — it was his duty to adopt their traditions, rather than hold onto a life left behind elsewhere.

Wang no longer considers Chinese New Year as important to his identity as it was before. He still values it, but chooses to focus more on traditions widely celebrated in the area. While his Chinese roots have slipped into the background, he doesn’t feel himself growing more American either. Rather, he sees himself as part of the entire world, taking in new cultures as they come, regardless of their origin.

“I feel like I am just a person on earth,” Wang said, “People all need to rest, relax, celebrate holidays.*”

In the past twenty years, China has faced unparalleled amounts of change — so according to junior Ritta Liu, in the face of a changing China and a new life in America, the old energy of celebrating the New Year has shifted on both sides of the globe.

For Liu, much the New Year spirit — as well as its signs of change — was embodied in watching CCTV’s New Year’s Gala, a ritual for her and her family, and a cultural icon. One of the most watched television shows in the world, it attracts 800 million viewers every year.

“They would prepare the show months ahead, because literally everyone will be watching,” Liu said, “If you appear on that show, you are the very best — everyone who appears on that show is really popular.”

Liu had nothing but happy memories of celebrating the New Year in China. However, she felt uncertain about what she would see if she went back.

“Not everyone’s like me — not everyone’s into Chinese New Year, so some people don’t really see it as big as a deal as it was before,” Liu said, “[China has] become more modernized.”

Liu said that this was a result of commercialization — a growing number of businesses beginning to capitalize on culture. In the past, for the next two months after the New Year’s Gala aired, viewers passionately discussed their favorite performances. But then new shows appeared, dividing viewers into watching different shows. There became less to talk about, and the spirit in the CCTV gala couldn’t carry on.

“Not everyone’s like me — not everyone’s into Chinese New Year, so some people don’t really see it as big as a deal as it was before.”

Liu also said that because of commercialization, people began to see the New Year less as a meaningful celebration and more as an excuse to spend money excessively, even on non-holiday items. As a result, China has seen a slight shift from celebrating family to cashing out.

As for how the New Year compares in Cupertino, Liu noted that it is less commercialized in this area. With people focusing less on hanging up decorations and such activities, they care more about spending time with loved ones. There also becomes a stronger focus on beginning anew into the New Year.

Like others from China, Liu agreed that New Year celebration is weaker here in Cupertino. But to her, that does not mean that American influence is completely taking over Chinese culture.

“The traditional families still acknowledge [Chinese New Year],” Liu said, “…It’s still a big thing. You just don’t have as big as a celebration, but it’s still a big thing.”

*Translated from Mandarin Chinese