They were the enemy, he thought. The death of the Japanese soldiers was supposed to represent America’s triumph, but something just didn’t feel right about thinking like that. A wallet next to the dead Japanese soldier caught his eye and inside rested a picture ofa woman and two kids. No, a widow and fatherless children. A wave of uncertainty washed over him. He couldn’t just go back to camp and say he felt sorry for a Japanese soldier, yet there was an overwhelming burden of silencing those emotions.

A room full of students at Cupertino High School listen intently to FUHSD substitute teacher Richard Klokow, a 90-year old World War II veteran, reliving that moment and finallyletting go.

“After 70-some years, that’s the first time I spoke of what my thoughts were before, which was a powerful thing in the sense that I wasn’t really holding it back,” Klokow said. “I felt free to just say it.”

Coming home marks the end of a veteran’s service. The battle scars and wounds that exist on the surface may inhibit them physically, but the emotional journey is just as challenging. Regardless of the wars they fight in, veterans are connected by their experiences adjusting and settling down: their experiences after the war.

PRESIDENT OF Cupertino Historical Society Donna Austin was only a child when World War II ended, but she distinctly remembers the joy felt throughout the city.

“Every bell in Santa Clara Valley was ringing and ringing and people were outside banging pans and yelling that the war was over,” Austin said.

According to Austin, people who had relatives in Cupertino came back to work on their family farms, and others began to slowly move into the city because of its natural beauty. The steadily growing population was seen as an opportunity for more businesses, including the Vallco shopping center, and farmers began to sell their land to account for growing housing costs.

“This whole place was all blossoms, and in the spring we would have blossom drives through the valley,” Austin said. “It was called the Valley of Heart’s Delight, and it truly was.”

Introduced in 1944, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, also known as the GI Bill, was the other key factor that increased the population by providing benefits to veterans. The new bill ensured zero down payments on home loans and low interest rates, which allowed veterans to obtain secure housing

De Anza College has carried on its history with the GI Bill, with a Department of Veterans’ Affairs to provide the support veteran’s need to complete their schooling. According to Attila Ujvari, an employee at their office on campus, veterans get help with anything from mental health issues to seeking employment, or finding out which classes to take.

“Some of [the veterans] have problems with something as basic as walking down the street, and they have to cope with themselves not just as a person who was deployed but as a student with different identities,” Ujvari said. “We try to help them

WHEN KLOKOW ENLISTED in the military he was only 5-foot-5, 118 pounds and 17 years old. But he knew it was what he wanted to do.

“At the time when you’re 17 everything is okay,” Klokow said. “Except for a few mornings in boot camp, then I would think I’d like to be home with my mom instead of getting up at four in the morning.”

He went to radio school and was responsible for preparing electrical generators and batteries, but experienced the danger and fear of being stationed where there was active fighting. A daily work day kept him busy, and the danger that loomed over them kept him alert. Klokow still has several fond memories of his experience, one of them being Thanksgiving of 1942.

“I filled my dungaree [blue jean] jacket with turkey from a supply ship for my friends back at the base, and I was going over to the other side and the naval officer said, ‘What you got there?’” Klokow said. “I told him ‘some turkey for the marines. What are you going to do about it?’”

After Klokow’s service, the GI Bill provided educational benefits so he could attend Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin for a degree in electrical engineering. He was handling a busy life with his family and schooling, yet his young age allowed him to adjust to the new lifestyle. He also believes the mentality of veterans of World War II helped with the settling down and moving on from his past.

“What we did was we said we did it, we served, they’re giving us a fine education here, that’s the end of it,” Klokow said. “Don’t dwell on the past and don’t let your life be defined by the fact that you served four years.”

After his education and retirement, he saw that MVHS needed a new football coach, and after coaching for a season, decided to substitute for teachers.

“It’s been a very pleasurable part of my life although now, it’s a little harder to get up at 5:30 in the morning.” Klokow said.

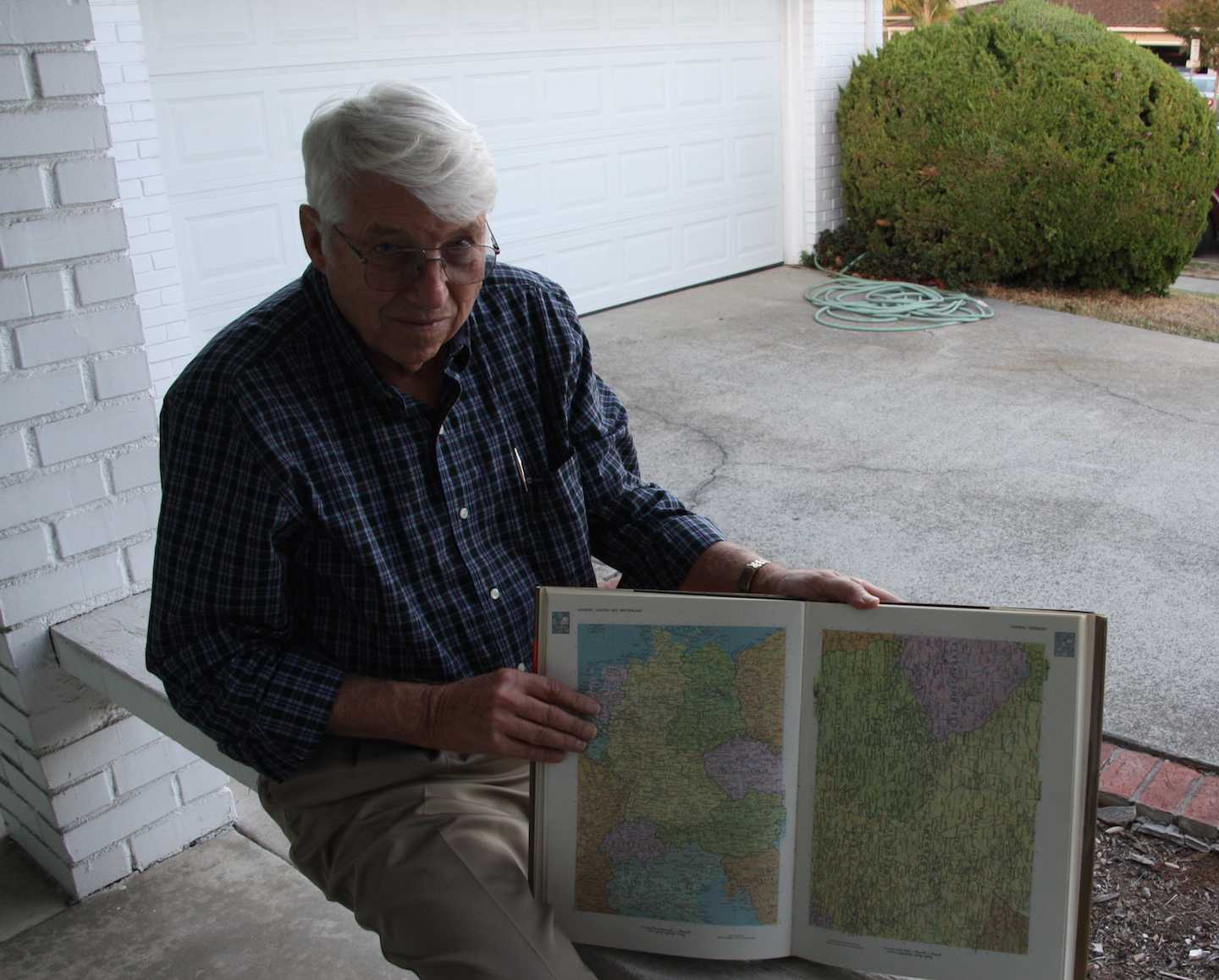

CURRENT CUPERTINO RESIDENT John Zwaanstra was stationed near Frankfurt, Germany during the Vietnam War. His situation wasn’t exactly like that of Klokow: he entered the military as an adult, lived in military housing with his wife and worked the same job he went to graduate school for. But as with Klokow, there was the danger of being stationed amidst the fighting.

“There was an undercurrent that this could all explode in a matter of hours,” Zwaanstra said. “It wasn’t exactly a friendly situation.”

As a doctor, there was a lot of similarity to his life back home, but Zwaanstra quickly became acquainted with the differences. He experienced more cases of burn injuries, gunshot wounds and radiation.

After his service ended, he worked on the reserves for a couple of years, and came back to America. When he moved out to Calif., he bought a house in 1979, the same house that he still lives in to this day. His two sons went to MVHS, and he retired. The city has changed a lot since then.

After being out of service for almost 50 years, Zwaanstra’s concerns and memories of the war have been dampened. Having time to relive his experiences has taught him about the nature of war itself, rather than his personal development.

“When you go around and see how cruel people can be to one another, you realize there’s a lot of evil in the world,” Zwaanstra said.

For veterans, settling down and starting a family takes time, but experiences of triumph or defeat affect how veterans allow their involvement in the war to shape their new lives. It’s not just “after the war”, but a continuation of their lives.