or the first 39 minutes and 47 seconds of the

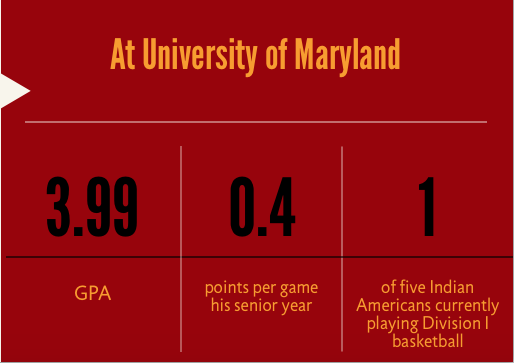

, 5’9’’ and 155 pound senior guard Varun Ram, one of the five Indian Americans currently in Division I basketball, was at his usual spot on the bench enjoying the glory of March Madness. But with 13 seconds remaining and the Terrapins holding onto a 65-62 lead, Ram was called into the game for his lock-down defense.

After the inbounds pass, Valparaiso guard Keith Carter received the ball at the wing with Ram tightly pressed on him. And with under ten seconds left and with the Terrapins playing right on top of their assignments, Carter was unable find an open man. He tried to create a shot for himself by driving towards the corner, but right when he was about to pull up for a three, Ram knocked the ball out of Carter’s hands. Time ran out and he was stormed by his Maryland teammates, but all for one play that will never show up in any stat sheet or record book. He wasn’t the leading scorer. He wasn’t even involved in giving his team the lead. But what he did was make the game-winning stop in the biggest college game of every Terrapin on the team. In the biggest moment of his life, he pulled through and finally, he and the entire Indian-American community have earned the moment they truly deserve.

The impact by @VRam_21 to help Maryland win yesterday goes beyond a game for Indian-Americans. @dcsportsbog explains http://t.co/GVJV83EPNv

— Kevin Negandhi (@KNegandhiESPN) March 21, 2015

I first heard of Ram about two years ago from my cousin, who is very close friends with him and his sister through each other’s families. I followed him and the Terrapins intensely after finding out about him and was ecstatic when I heard that I would have an opportunity to see him at his cousin’s arangetram, which is an Indian dance performance. My cousin introduced him to me after the arangetram ended and we went on to have a long conversation about his journey in basketball and my journey in football. His story was a story very similar to mine and many other Indian American athletes at MVHS.

At MVHS, Indian American athletes are often told by their peers that they cannot play college sports, most of the time because of their race. It’s what has been installed in their brains. They are taught to only focus on academics because it is the only way to be successful in life. Although there are many students who wish to play college sports, they tend to shy away from it because it is a path that so few people of their race follow. But now that Ram has shown that it is possible, he has opened the door for me and so many others at MVHS and the entire country.

Unlike most Division I basketball players who sign their letter of intent on National Signing Day their senior year of high school, Ram took a much more roundabout path to get to where he is today. Like myself and many other Indian-Americans, Ram was raised in a family that prized academics. His mother earned a PhD in biochemistry and is a toxicologist for the Environmental Protection Agency while his father worked an information technology programming manager for the National Weather Service. His parents wanted Ram to follow down an academic path like his sister Anita, but Ram wanted to play basketball.

Most parents of first generation Indian-Americans have never been able to experience the true meaning of sports themselves because for generations and generations, Indians haven’t treated sports, other than maybe cricket, as more than a pastime or hobby. Along with that, there just hadn’t been any significant examples of Indian American professional athletes (zero 100 percent Indian athletes in the NFL, NBA or MLB) to prove to parents that aiming to play in college or professionally is even a possible option.

“Our parents, they go by the visual,” Kevin Negandhi, the first Indian American national sports network anchor, said in an interview with the Washington Post. “The only way you can show them you can do it is by giving them an example. And the example was on national TV, making the play of the game. That’s how we can change minds.”

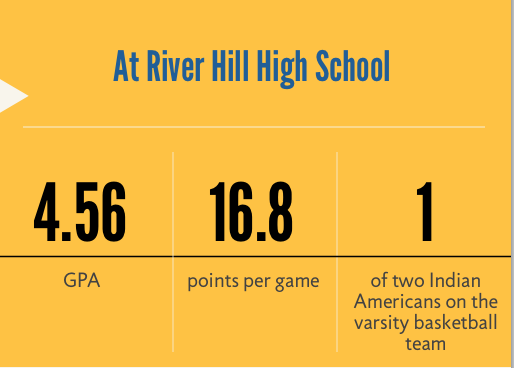

It took a while for Ram to convince his parents to let him pursue his passion, but eventually they gave in. And since middle school, Ram had been aspiring to play basketball at an Ivy League school so he could get the best out of both worlds, academics and athletics. After he boasted a 4.56 high school GPA and averaged 16.8 points per game his senior year, he received some interest from Ivy league school s. But when his senior year came to a close, he still had no offers from them. Instead, he was suggested by schools that were recruiting him to attend a post-graduate basketball prep school, The Winchendon School, where he

s. But when his senior year came to a close, he still had no offers from them. Instead, he was suggested by schools that were recruiting him to attend a post-graduate basketball prep school, The Winchendon School, where he

could refine his skills and be more beneficial to their team. When Ram’s parents heard about this they hesitantly let him follow through with it but with the hope that it would empty his passion for the sport so he would be able to focus on academics.

“I supported him because he was so passionate about it,” Ram’s mother said in an interview with the Baltimore Sun. “I did give him one chance to go to Winchendon, but then he had to forget about it and go to college and do something on the academic side.”

After his year at Winchendon, Ram didn’t hear back from any of the Division I schools that were once interested in him, so he decided to play at a Division III school called Trinity College. Ram spent one year there, averaging 7.8 points, and decided that he would transfer to the University of Maryland, College Park because he felt like he wasn’t satisfied with his life, both athletically and academically. He was told by family and friends that he would have to give up his basketball dreams by transferring to a major conference Division I school that many thought was way out of his league. Still, Ram was persistent, training all summer to help better his chance of walking onto the team.

“The first time I came in here [for tryouts], I had chills,” Ram said. “I knew, even if basketball didn’t work out, it was the right decision [to transfer]. With basketball working out, it made everything that much better. It was like icing on the cake.”

Even while playing Division I basketball, he was still able to maintain his grades, coming two A- short of a perfect 4.0. And although Ram had to sit out his first year due to eligibility issues, his drive and determination kept him going and payed off when he was given a scholarship before the start of the 2013-14 season. As a reserve player for the past two seasons, Ram’s impact on the team was easily overlooked by outsiders. He has always been a scout team player, but has helped his teammates improve tremendously because of his effort. This year, he had one role during practice, and that was to get in the face of star freshman point guard Melo Tri mble. His constant defensive intensity helped mold Trimble into one of the best freshmen in the country.

mble. His constant defensive intensity helped mold Trimble into one of the best freshmen in the country.

For most of his career at Maryland, Ram only played garbage-time minutes. His best game, stat wise, in his college career was three points, three rebounds, and three steals. But no matter how little he played and how little he contributed to the stat sheet, the importance of his role on the team was unmatched. And finally, when all of the stars aligned perfectly, he was able to make his impact on the court be felt by not just his team, but the entire country.

It wasn’t just a play that made him an instant celebrity and the most trending subject on Twitter. It was a play that proved to myself and so many other Indian American athletes that it’s possible. It’s possible to come from a heavily Indian background and be able to chase your athletic dreams and still be successful in academics. Yes it is extremely hard, but Ram did what it took to be at the highest level in both. In my conversation with Ram, he told me that all he did all of high school was basketball and school work. It may not be the most exciting lifestyle, but for him, myself and many other other Indian American athletes, especially at MVHS, the only way to continue playing sports is by being academically proficient as well.

I would even go as far as saying that, to an extent, what Ram has done for the Indian American community is similar to what Jeremy Lin has done to the Asian American community. Like Ram, Lin excelled at both academics and school and defied the beliefs of what is possible for him to achieve. Both took the national spotlight in a matter of moments and have inspired athletes of their respective races to strive to reach for the highest level in sports and academics. And although Ram’s impact is felt less throughout the country, those who know his story, such as students at MVHS, know how monumental an example he is to Indian-American athletes.

“Just do what most Indian kids do, just go study, and your life will be okay,” Ram said during an interview with the Washington Post, remembering what skeptics had told him. “That’s why I’m so happy that my parents have been so great to me, because I think it’s opened people’s eyes. This is more than just a game. You can do so many other things with it. You can balance academics and sports.”

Ram has shown that there is nothing that can determine what you can do and what can you be. Just because he’s Indian doesn’t mean he has to fit the stereotype of being a doctor or a lawyer or an engineer. Just because he is 5’9’’ and only weighs 155 pounds, doesn’t mean he can’t be a basketball player. Just because he has been told by just about everyone that he can’t play Division I basketball, doesn’t mean he can’t. Defying all odds Ram has persevered through all the hardships and naysayers and what better way to possibly end his basketball career with the moment of his life.

“The man’s a hero to me,” Maryland forward John Graham said about Ram.

Varun Ram, not only are you a hero to Graham, but you are also a hero to all of the Indian-American athletes chasing their dreams.