It was Friday the 13th when senior Dmitriy Gutnik fell. At school soccer practice in December 2013, Gutnik received the ball and dribbled it past the defender. He started to sprint, but the defender stuck out his leg and caught Gutnik’s foot. The whole lower part of his leg twisted, locking up as he fell. The team went silent. Gutnik rolled on the field as he tried his hardest not to scream.

Two weeks after the fall, Gutnik received confirmation with an MRI scan. He had torn his anterior cruciate ligament or ACL. Although he was ready for surgery as soon as he found out, his family could not cancel their annual trip to Lake Tahoe. Gutnik watched them ski and waited. Waited for his final MRI results. Waited for the surgery. Waited to be able to play soccer again.

The anterior cruciate ligament is one of four ligaments in the knee. Like a rope that connects the shin and thigh bones, the ACL helps guide the movement of these bones as the body pivots. When an athlete hears that familiar “pop,” the rope has been broken. For MVHS athletes, an ACL forces an unwanted break in their sports careers.

One of the most cumbersome parts of the ACL healing process is waiting. The typical patient with a torn ACL takes about a year to return to normal athletic ability. For Gutnik, this meant months of practice, college showcase opportunities, countless games and a school sports season missed.

However, that same intense training is the probable culprit of the athlete’s ACL tear. Since 2002, the risk of athletes tearing the ACL in the U.S. has gone up by 400 percent according to doctors in Philadelphia.

As youth sports become more competitive than ever, athletes feel the pressure to play their sport yearlong. The payback: their bodies bear the burden. A former flyer on the MVHS cheer team, junior Ashley Win endured jumps, kicks, and stunts. But a toss in the air always left a sense of uncertainty on the way back down.

“When [people] see cheer, they’re like, oh, pom-poms and cheering,” Win said. “But it’s actually the most injury [prone] sport ever.”

It was January 2014 when Win’s body answered to the toll of her yearlong sport. In the middle of a jump, snap, her leg bent inward in half. She’d always had a high pain tolerance, but this one hurt. After a couple of visits to the doctor, Win received her results. Bone contusion. Sprained MCL. Torn ACL. She had had no idea the injuries were there.

Dr. Jeffrey Bui, an orthopedic surgeon at Kaiser Permanente in Santa Clara, has noticed that a year-round sport often corresponds to fatigue. The ACL cannot handle the constant stress of exercise without rest.

“When athletes participate when they’re fatigued,” Bui said, “their muscles don’t have the same ability to absorb shock. It puts [the athlete] in a compromising position.”

However, for most athletes, stepping out on training isn’t an option. No potent strategies to prevent ACL tears have been discovered, so most patients opt for surgery. In fact, methods of ACL repair have become so advanced that some athletes can return to play after only five months, which is less than half of the usual recovery time.

Senior Jasraj Ghuman, a varsity football player, succumbed to a consecutive partially torn left and a sprained right ACL during the last two years. But for him, the injuries were a pause, not a setback. With rehab and a knee brace, Ghuman was able to continue play in the 2013 and 2014 seasons.

Still, Ghuman has become more cautious in play.

“If there is a tackle, you double guess jumping on the pile,” Ghuman said. “You don’t go as hard as you would have.”

Dr. Bui himself has observed the psychological toll of an ACL injury. Although the body can heal, minds do not forget the wounds so easily. Ghuman is more careful on the field. Win quit cheer in fear of tearing her other ACL and now devotes her time to yearbook. Gutnik still remembers the sleepless nights from after the surgery. Fixing an injured ACL means waiting— painful, tiresome and expensive waiting.

The worst part of the physical and mental process is the week after the surgery, after the painkillers fade away. For Gutnik, the week was the worst of his life.

“Whenever I tried bending, it felt like a steak knife being jammed into my knee.” Gutnik said.

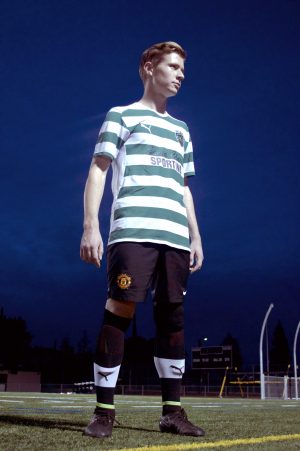

Nonetheless, Gutnik furiously tackled the rehab process to beat the injury as it had beat him. Deemed “recovered,” he has returned to his premier Santa Clara Sporting team and plans to join the varsity boys team at MVHS as well. The injury has completed its cycle.

Yet, Gutnik’s intense schedule does not change. His weakened ACL will now bear the same burden as before. He is a marked man, six times more likely to retear his ACL than before and at a higher risk of arthritis and other knee injuries.

Now, a year later, Gutnik is back on the upper field at school soccer tryouts. He laces his cleats, does two high knees and runs onto the field with his knee brace as the only visible reminder of his surgery. Even though he knows the risks, his love of the game outweighs his fear of retearing his ACL.