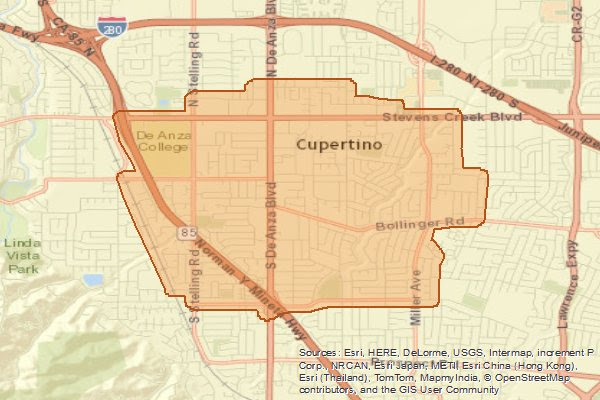

t 11 pm. on Sept. 18, Santa Clara County Vector Control District (SCCVCD) plans to fog the area between Stevens Creek Blvd. and Rainbow Dr. with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-approved insect repellant in order to prevent further spread of the West Nile Virus.

The West Nile Virus (WNV) is a disease transferred by birds and mosquitoes. Though it originated in Northern Uganda in 1937, it had travelled to the U.S. by 1999 through what scientists believed was illegal pet trade. By 2004, WNV had hit the Santa Clara County.

“I’ve seen a lot of houses being fumigated around my neighborhood as well as neighboring neighborhoods,” Kannan said, “but it hasn’t come to the houses directly around mine.”

Science teacher Andrew Goldenkranz, who has been following the WNV issue since it became prominent in California, sees the virus as a growing threat.

“[WNV] is pretty close to global already,” Goldenkranz said. “Any place you have rainy season, you’re going to have to worry about mosquitoes.”

Until recently, WNV had never been a widespread danger, but a mutation that allowed WNV to be even more virulent made the virus a perpetual threat.

“We’re having a record-breaking year,” said Russ Parman, the directing manager of SCCVCD. “What happens in a drought year is that this whole back-and-forth cycle between birds and mosquitoes happens even more quickly because the birds and mosquitoes are, on average, closer together, both exploiting these scarcer water sources we see in a drought.”

In previous years, SCCVCD has had to conduct an average of three to five foggings in the county per season. Thursday’s fogging will be the nineteenth this season.

“It seems to be a growing issue,” Kannan said. “Hopefully [SCCVD] will be able to put it down before it becomes like the H1N1 outbreak a few years ago.”

Lethal pestilent, harmless fog

The pestilent SCCVCD will use in Thursday’s fogging is called Zenivex, a substance containing the synthetic material etofenprox. A warning email was sent to all households that would be included in Thursday’s fogging, but Parman believes that there is nothing to worry about. SCCVCD uses ultra-low volume technology to spread three tablespoons of Zenivex over the area of a football field.

“[Zenivex] is less toxic than table salt, and about 200 times less toxic than caffeine,” Parman said. “To have a 50 percent chance to kill yourself, you’d have to inhale about two football fields’ worth of fog. It’s not likely that anyone is going to come microscopically close to accomplishing that feat.”

The fogging is happening at night primarily to evenly disperse Zenivex without human interruption and because mosquitoes are more active throughout the night. Though Goldenkranz plans to stay indoors on Thursday, he is aware that the fogging is safe.

“I still wouldn’t be happy if I was walking on the street with my dog and got a big dose of the fogging,” Goldenkranz said, “but that’s probably an emotional reaction.”

A rising threat

According to Parman, WNV is widely unreported because around 80 percent of WNV patients recover without showing any symptoms. However, another 19 percent experience West Nile fever, which ranges from headaches to high fevers and to rashes. The final one out of every hundred patients has more serious symptoms.

“In less than one percent of cases they get what’s called a neuroinvasive form, and that’s where it invades the nervous system, like the spinal cord and the brain,” Parman said. “Then we start seeing stuff like encephalitis and paralysis and meningitis.”

According to Parman, one of every ten neuroinvasive WNV cases are fatal.

So far, five Cupertino residents have been diagnosed with WNV: two with no symptoms, one with West Nile fever, and two with neuroinvasive WNV. The three residents who showed symptoms were all hospitalized.

“There is no vaccine, and there is no cure,” Parman said, “so what we’re doing is the only approach, and that’s prevention. We do that by very extensive public education and spending a lot of time finding the larvae in the water.”

To learn more about SCCVD’s foggings and other safety measures being taken:

http://www.sccgov.org/sites/vector/Documents/2014-Zenivex%20E4%20MSDS.pdf

http://www.sccgov.org/sites/vector/Documents/2014-Zenivex%20E4%20MSDS.pdf

http://www.sccgov.org/sites/vector/Pages/vcd.aspx