[col type=”1_3″ class=””]

[/col] [col type=”1_3″ class=””]

[/col] [col type=”1_3″ class=””]

“No, no! I’m only taking it if it’s forty.”

“It’s fifty!”

“Fifty? Well, that’s just a crime!”

[/col] [divider type=””] [col type=”1_2″ class=””] [dropcap1]”Fifty! Fifty! It’s fifty!”[/dropcap1]

The woman huffs and scurries back into the crowd, tugging a stroller full of empty birdcages, used watches and ivory-handled daggers.

People of all ages wander among gardens of lacquered wood, foggy glass and cast iron, their foldable carts ready to be filled.

At the De Anza College flea market, held on the first Saturday of every month, vendors treat their merchandise as artifacts of lost decades — nostalgia and memories captured by a broken chair or a cracked clock. A tight-knit community bearing bad weather and poor sales, they are committed to spreading stories and expressing the eccentricities of life through everyday objects.

“Every [city] has its own collection of things,” vendor Jackson Pennet said. “People pay a lot of money for the past. You see all of this, all of my stuff? They’ve all got stories to tell. So who’s gonna tell ‘em? Who? Are you gonna let history go in the trash?”

He shakes his head and continues to mend the handle of a ceramic teapot, turning the mug over and pointing at four words written along the rim. “To mama. So sorry.” Its price tag reads “Fifty cents. Is not new.”

[/col]

[col type=”1_2″ class=””]

“See that? That’s a story,” Pennet said. As a flea market veteran of 40 years, Pennet has sold all types of ceramic products, from broken dolls to tea caddies.

“The De Anza flea market has always been the best. I’ve sold books for about 30 years, and this is the only market I come to,” vendor John Bear said. “To tell the truth, today is not such a good day. But that matters less. Meeting people matters more.”

Despite the struggles of the recession, Bear continues to be a part of the vendor community, where making money is not always the best kind of success.

“I’ve been coming here for eight, ten years,” customer Al Mattel said. “If John’s here, I’m here.”

He met Bear at a flea market nearly a decade ago, and since then, they’ve maintained their friendship beyond the market.

Mattel explains that he has always been drawn to old clocks and timepieces. To him, the flea market is an opportunity not only for profit, but for the satisfaction of restoring something broken or damaged into an heirloom.

“I bought a clock made in 1906 here and I fixed it up a little. And now it’s worth a thousand bucks. I only paid $25 for it,” Bear said. “There is no greater thrill than this: It was in such bad shape before, cracked glass and everything, and now I can give it to my kids.”

A Matter of Faith[/col] [divider type=””] [col type=”1_2″ class=””]

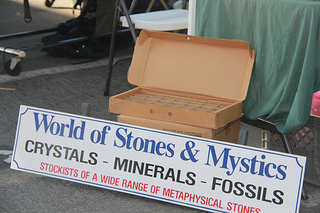

[dropcap1]Down the row[/dropcap1] of white tents, signs with bold red type scream “Buy here!” to the passerby; one advertises “Timeless watches,” another proclaims that “Fashion is here.” And one such sign, propped up against a crooked table, publicizes a wealth of “Metaphysical Properties.”

“Metaphysical? Do you want to know what metaphysical means?” vendor Henry Pikoos said, gesturing with his hands.

“It’s amazing. It means something that’s there, but it’s not there…It means we can trace back the history of the world just by looking at stones,” he said.

Pikoos stands amidst his own personal quarry, jagged purple amethyst lined up on one side and dishes of clover-shaped quartz on the other.

“A lot of people come and see me, and they say ‘I’ve got a problem with my back, I’ve been taking medication and nothing’s helping!’” Pikoos said.

Customers linger behind pendulum displays and pause to listen.

“And I say, ‘I’ve got a stone for maybe three or five dollars and it might be good for you. Stop taking the medicine and take a stone,” Pikoos said. “People of course don’t believe. But I say, ‘It’s not about believing.’ It’s about feeling.”

Pikoos explains that he had been battling a sore throat for nearly eight months. After a combination of antibiotics and antihistamines, Pikoos’ miracle cure came in the form of a circular pendant, speckled blue and white.

“It’s azurite with malachite, which people say is the crystal for respiratory problems. And look. I’ve had it on for three weeks now, and I haven’t coughed yet!” Pikoos said.

[/col]

[col type=”1_2″ class=””]

He pats his chest and cups the pendant in his hands, faithful despite people’s skepticism.

“It’s like asking if there is a God. I don’t know, no one knows. But it’s like there’s something there,” Pikoos said. “I mean, look at what the crystals are telling us. They know. They know that we are coming to the end of time, the end of the world.”

To him, crystals are not merely shiny baubles or pretty jewelry. They are a powerful way to gauge the world, objects of divine power beyond human understanding.

“There is so much we do not know,” he said. “But look, don’t you feel the energy in stones? Isn’t that why people are drawn to them?”

He is interrupted by a wide-eyed bystander, who balances a square black pendant on the palm of his hand.

“Well, what does this one mean?” customer Roque Cervantes said.

“Ah. This is onyx…” Pikoos rifles through a dog-eared book. “Good for times of pain or sorrow…”

Cervantes is skeptical and asks whether these so-called properties are simply a matter of faith.

Pikoos sets down his book and answers with a single word: “Maybe.”

Passing Down History

[/col] [divider type=””]

[col type=”1_2″ class=””] [dropcap1]One row away[/dropcap1] and three stalls down, father-daughter vendor team Roger and Carrie Judd converses with customers. Shopping at flea markets was once an essential part of their childhoods, and now they return to a familiar world.

“I always just liked stuff when I was growing up. I loved treasure and treasure-hunting, and my dad had a furniture store up in Campbell in the late ‘50s. I was always intrigued,” Roger Judd said. “And when I was 18, I refurbished my first chair. That was it.”

His daughter Carrie has been aiding her father for the past two years, traversing the Bay Area with hundreds of pounds of glassware and fine-bone china in the back of their van.

“I feel like I’ve been doing this my whole life,” Carrie said.

On the Judds’ tables, the past is arranged on like a calendar of objects: jug from the ‘60s, dish from the ‘80s, teacup from last week.

“Think about it this way: we all like to keep old things,” Roger said. “Our grandmothers kept old things, too, and their grandmothers kept things as well. This is history.”

[/col]

[col type=”1_2″ class=””]

He gestures at his inventory, at the stalls that stretch across the De Anza parking lot, each boasting a unique collection of objects. Sometimes damaged but always beloved.

“You see? All of these objects, even everyday objects, are part of our history,” Judd said. “We’re all just passing down history.”

Behind booths of fading antiques, there are people with histories as diverse as their merchandise. Local mystics, retired school teachers, professional knife-handle makers: they all gather at the Saturday market with their children and friends, exchanging stories as easily as goods.

“Kids think Cupertino is boring? Well, of course they do,” vendor Judy Garcia said. “You know, they just need to get out of the house…and meet us!”

[/col]