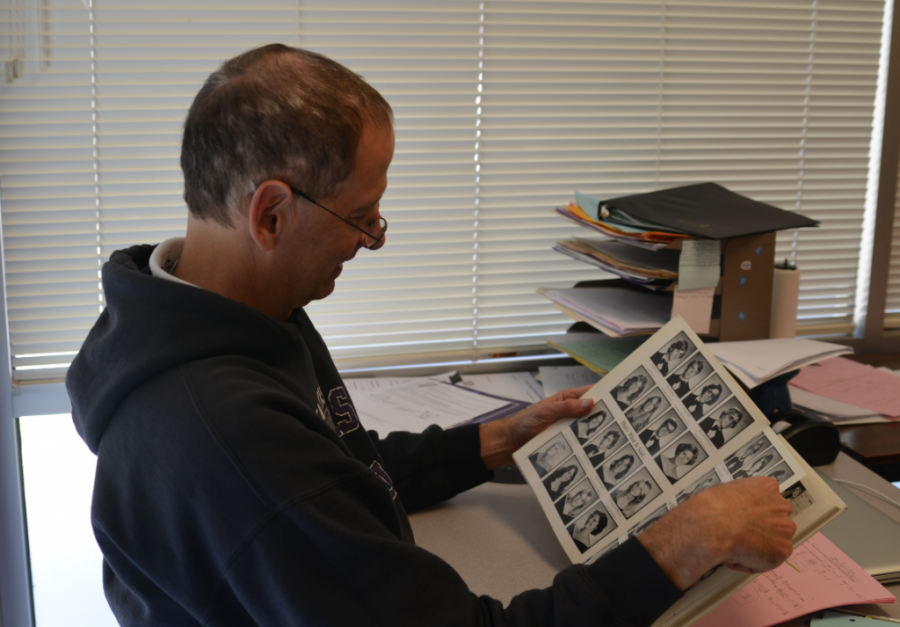

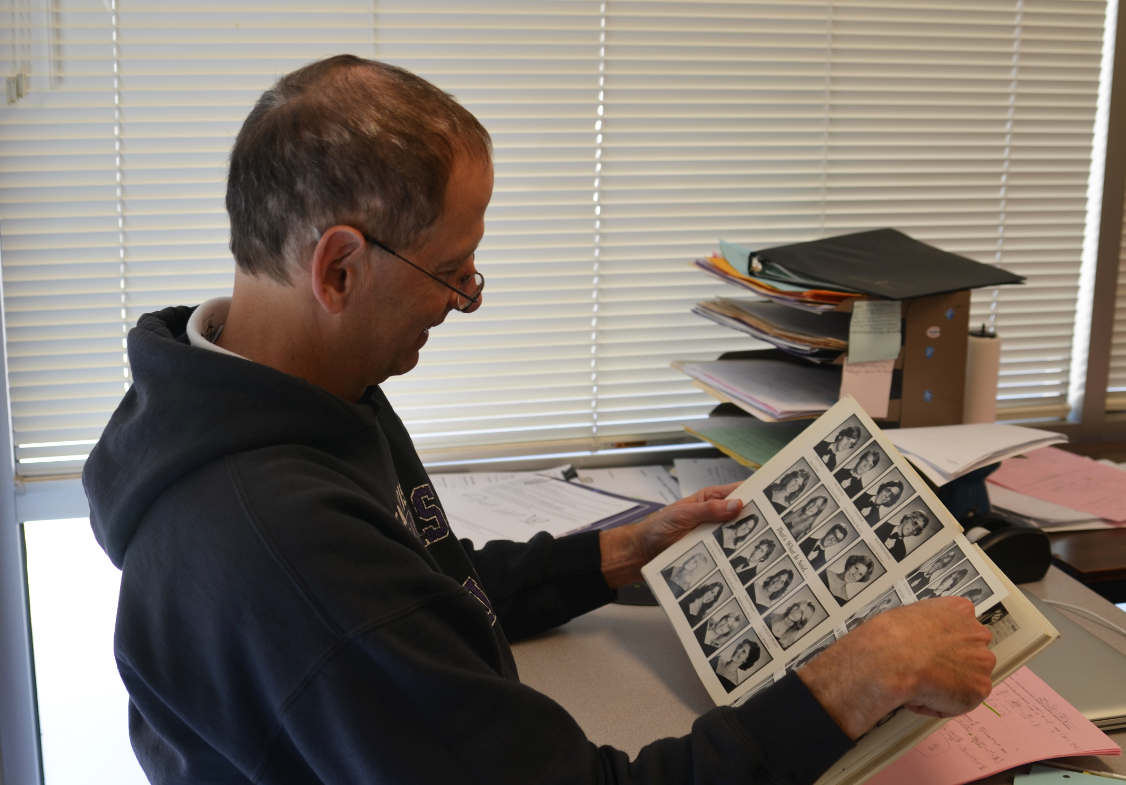

[dropcap1]I[/dropcap1]t was the last week of school in the year 1978. Math teacher Martin Jennings, then a senior in high school, signed the yearbook of a friend and started toward his car after giving it back to her.

At the entryway of the parking lot, he heard her cry.

She was a freshman who went to a dance with him at the beginning of the year. Shortly afterwards, they started dating. Toward the end of the year, however, they had parted their ways. When the girl came to Jennings to sign her yearbook, he decided to give her some advice on dealing with her future relationships — advice that was not meant to be taken as criticism; but it was to the girl.

Unknowingly, Jennings wounded her feelings. He meant no harm, yet his miscomprehension of her point of view did the job. It was a lesson in empathy.

According to “Empathy and conflict resolution in friendship relations among adolescents” by Minet de Wied, presence of empathy results in more successful conflict management and thus stronger friendships. On the other hand, lack of empathy often causes misunderstanding and hurt. And it was the case for Jennings,

who only realized his mistake afterwards.

“If [you are] going to [give advice], talk about it in a place where people can talk instead of writing in a place where people look for memories for many years to come,” Jennings said. “That’s not the right form.”

He also tried to decipher his own psyche. Looking back, Jennings believes he wrote those comments because of too much ego. Senior year had been a triumphant one for him until the yearbook incident: He was doing well in sports and academics and also won a scholarship. He was proud.

[quote_right]”I couldn’t apologize to her because I never saw her again.”[/quote_right]

“Things that hadn’t happened to me my whole life were happening during those last spring months of the school year,” Jennings said. “So I just think that my head got too big, and I thought I knew more than I did.”

He was right. Back in high school, Jennings did not realize that relationships may be a more sensitive topic for some people — a realization that came to him only after the words were written in the girl’s yearbook, and the hurt was done.

“I couldn’t apologize to her because I never saw her again,” he said.

[dropcap1]A[/dropcap1] similar incident happened in 1992 when science teacher Pooya Hajjarian was an eighth grader and, like Jennings, unintentionally hurt his close friend.

“Growing up, my dad has always told me the one thing you never do is never hurt someone intentionally,” Hajjarian said.

Nevertheless, he felt guilty about unintentionally wounding his friend’s feelings with a joke. Jokes, in his opinion, were important in maintaining a good friendship. However, he did not realize that the jokes he and his friend group made had become targeted at one person, which required a degree of self-awareness he did not possess as an eighth grader.

When the friend who felt hurt opened up about his feelings to the group, Hajjarian was shocked. He recalls how he and his other friends had to think back on the jokes they made to find out what was hurtful. After that, he became more careful about his words.

“A lot of the times we say things just to say things, but we don’t think about how those words can be perceived,” he said.

Unlike Jennings, Hajjarian kept in touch with his friend throughout the years. However, regardless of whether the misunderstanding was cleared, the two teachers both attributed their mistakes to not knowing how to detect or protect their friends’ feelings. They weren’t aware of the importance of empathy at the time. But now they are.