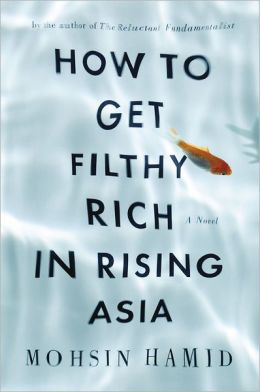

Book: ‘How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia’ is a work of art

April 21, 2013

Mohsin Hamid utilizes straightforward yet evocative language to paint the picture of a developing Asia.

Don’t be fooled by the title of Mohsin Hamid’s novel “How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia.” “Novel” is the right term. This book isn’t a real self-help book, but fiction through and through.

The protagonist of the novel is the second-person “you,” and the life “you” lead is a busy one; Originally living in poverty in the rural countryside, your father moves the family to the city, where you work your way up to become the tycoon of a bottled water company, all while your path intersects again and again with the unnamed “pretty girl.” (There’s only one proper noun used throughout the book, and it’s in the title.)

Hamid populates the city with broad yet economic brush strokes, taking time to describe aspects of it without becoming overly tedious. The city’s horrific tap water system — your reason for going into the bottled water industry — is detailed in a single paragraph of four sentences.

Similarly, characters like a vicious, resentful schoolteacher are briefly given a backstory as well. Your teacher feels jipped because as a second son he is unable to take advantage of the sole open position of meter reader, a role in which he would “not have to put up with children, work comparatively little, and what is more important have greater opportunity for corruption and are hence both better off and held in higher regard by society.”

These dynamics the city creates as well as the various aspects described make the fictional metropolis (based on Lahore, Pakistan) almost a character in its own right. Although the dialogue is sparse, we’re given a living, breathing picture of how the city interacts with itself and moves forward. All this serves to create the sense of a work of art. Instead of names, we’re given images. Instead of an old, established city, we’re given the freshly painted canvas of a developing world.

But because the work is so new, the concept experimental, there are still some hiccups along the way. At the novel’s beginning, the “self” referenced in self-help books is said to be slippery, and is used to create a weirdly forced reference that is vaguely pornographic in nature. Similarly, the ending of the novel lacks strength; what attempts to be conclusive and enlightening only proves to be vague and strange.

However, these are small gripes in the face of a brilliantly concise work. Although it may be lacking in concrete advice as to how to get you filthy rich, this novel is better than any economic self-help book, which, let’s face it, will probably set you back more than create profit.