Out of touch

Students share their experiences with straying away from their native language

March 18, 2022

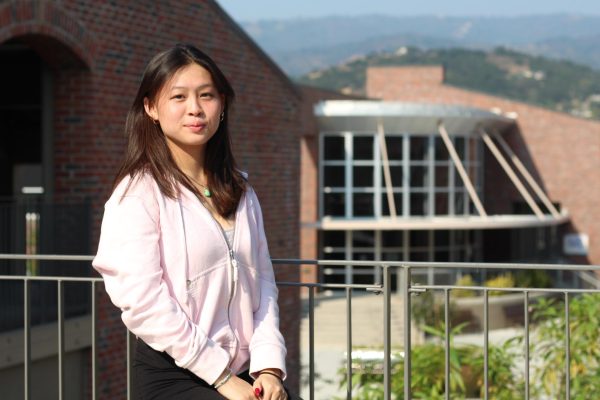

While walking home from middle school, now sophomore Elise Chiu recalls a moment when a passerby reached out to her in Chinese. Unable to understand what the stranger was saying, Chiu found herself shaking her head in bewilderment before apologizing and “awkwardly walking away.”

Chiu says the reason she doesn’t speak or understand Mandarin Chinese is because her parents were both born in America, making Chiu a second-generation American who lives a more “Americanized life.” For instance, Chiu finds that her family’s choice in vacation destinations reflects this disconnect with their Chinese culture.

“[My family] tends to go on more relaxing vacations rather than trying to connect [with my Asian roots],” Chiu said. “Also in general, since I have a little sister, she’s more interested in swimming and going to Hawaii as opposed to learning about [Chinese] culture.”

Instead of learning Mandarin and trying to close the cultural gap that many non-native speakers experience, Chiu is currently enrolled in Spanish 3. This choice was due to her parents feeling that learning Spanish would be more “applicable” to high school. Similarly, junior Anika Edara also takes Spanish, rather than learning how to speak her native language, Telugu. However, Edara chose Spanish for her language class because Kennedy Middle School only offered Spanish and French. If MVHS offered Telugu or Hindu, Edara said she would take those classes instead.

Edara’s willingness to learn how to speak Telugu stems from her receptive bilingualism, or her understanding of the language, but lack of ability to speak it. Edara attributes this to the fact that her parents never taught her how to speak Telugu.

“[My parents] would speak to me at home sometimes, which is why I can understand [Telugu] fully,” Edara said. “But I never had opportunities to [learn how to speak] it because most of my life I’ve been in school from nine to six [where] I’m always speaking English.”

Like Edara, sophomore Ethan Pham doesn’t speak his native Vietnamese, but he says it does not impede his connection with his cultural roots.

“I don’t really feel disconnected from my culture,” Pham said. “Because, I eat [a lot of] Vietnamese food and I still celebrate Vietnamese holidays such as Tet, [which is] a week long celebration for Lunar New Year’s where you celebrate by partying all day.”

However, Pham feels the repercussions of being unable to speak Vietnamese, particularly when ordering food.

“When I go to downtown San Jose and I try to order food, [the restaurant owners] speak to me in Vietnamese and then I’ll [respond] in English,” Pham said. “I feel really awkward because I can’t speak Vietnamese back to them even though they spoke it to me.”

Edara often finds herself in a similar situation when she travels back to India once every two years, mainly because she faces a detachment while communicating with her relatives. Despite her inability to communicate in her native language, Edara believes that “language isn’t the only factor in culture” because “there are still other ways to be immersed in a culture and to learn about it [besides speaking your mother-tongue].”

For instance, Edara’s parents try to engage her in Indian culture through ancient Indian stories from a Hindu epic, the Mahabharata. She believes that her parents do this because they find it impactful to share a story that will benefit her understanding of the culture.

Both Pham and Edara’s experience with culture causes them to want to learn their native language in the future so they will be able to connect with others in meaningful ways.

“It’s more internal [motivation] that makes me want to speak Vietnamese, [rather than social pressures],” Pham said. “It would be nice to have a conversation with my grandma and understand what she’s saying. It would also be cool to speak [Vietnamese] back to her [so she can better understand me.”