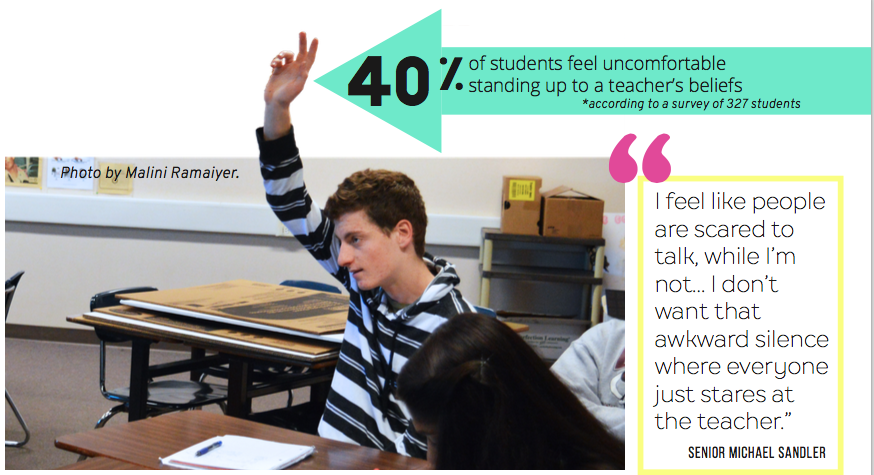

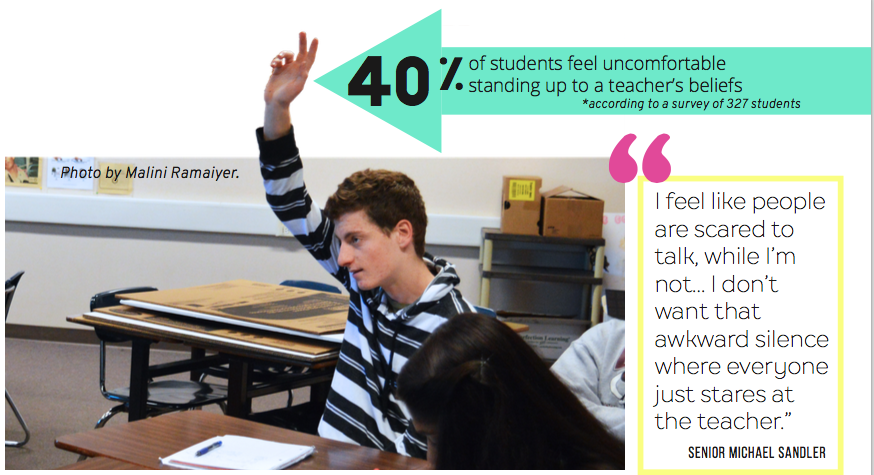

Correction: In the print issue of this article, photo caption wrongly stated Senior Michael Sandler’s grade. The correction has been made in this version of the article below.

When senior Michael Sandler disagrees with his AP Economics teacher Pete Pelkey, or any teacher for that matter, he raises his hand and lets the class know. Sandler has a simple policy — speak up when other people won’t or when he disagrees.“If no one’s raising their hand, I will probably participate because I don’t want that awkward silence where everyone just stares at the teacher,” Sandler said. “I feel like people are scared to talk, while I’m not.”

Beliefs can be shaped by experience, by upbringing, by environment — they are a sum of what a person is. Teachers and students, alike, have their own beliefs and ideologies, but what’s in question is how a teacher’s beliefs influence the classroom, and what happens when a student’s ideology clashes with another teacher’s.

Sandler challenges the established authority and a prescribed relationship between teacher and student, unafraid to question what is being taught.

“It depends how they disagree — if there is substance to it, then show me the logic, and if they give a logical point, I can concede a point,” Pelkey said. “If the kids don’t want to listen to anything I say, then that is not disagreeing.”

Math teacher Martin Jennings cites his Catholic background as the source of his ideologies, and his classroom is influenced by the values he’s learned throughout his life.

“I’ve just grown from being a part of a church and talking to people,” Jennings said. “The purpose of teaching isn’t to share those beliefs. However, it is important for those beliefs to be a part of how I interact with people.”

While Jennings does not let his personal views impact how he teaches math itself, his beliefs bleed out through his personal stories, or “commercial breaks” as he calls them. Commercial breaks are anecdotes about Jennings’ life, ranging from his experiences in Portland and gaining new perspective on racial identity, to interpersonal stories about friendship, shaping how he interacts with people. It is not required listening, but Jennings feels it provides a welcome break from academics.

“I want them to think about what makes sense for them,” Jennings said. “And maybe if what I am sharing opens their eyes, then that is a good thing.”

Jennings learned a long time ago from a teaching advisor that any reaction from a student is a good one. He understands that students can participate without speaking. Jennings has found that not all students are comfortable with raising their hands in front of the class and speaking up, so he is flexible.

“Even when students moan and groan at the lamest of my jokes, they are at least listening to the joke and are taking in what I am saying,” Jennings said. “There are students who aren’t comfortable with speaking, but they are participating.”

Jennings has a rather open interpretation of participation, while English teacher Jireh Tanabe considers critical thinking key to participation. With her Chinese upbringing, Tanabe was trained to memorize and repeat information, a “drill and kill” mentality when it came to education. But she soon realized that such rote memorization can be harmful. After teaching at MVHS, she sees that same upbringing manifested in students and structures her class to deconstruct that. She explained that literature requires deeper thinking, reading between the lines and moving beyond what students are comfortable with.

“It’s very difficult for them to move beyond what they’re comfortable with.” Tanabe said. “It is a challenge for me to come up with things in which they can feel like they can they can still do the assignment, do the thinking and grow from that.”

Jennings attributes much of his beliefs to his religious upbringing, but he does not let it limit his worldview. Jennings generally refers to the class as “Ladies and Gentlemen”. One student confronted him about what this expression meant to gender. But Jennings and the student were able to move past it after a talk conceding each other’s point of view.

“We just moved forward, and the next day in class I reassured the person that I cared about all the folks, not only the ones that think like me,” Jennings said, “I tried to listen to what they had to say, and they tried to listen what I had to say, and it hasn’t been a problem since.”

Sandler believes that he’s in a minority of MVHS who will openly disagree with a teacher, and Pelkey taught Sandler and found this to be true as well. The status quo in a classroom, they both believe, discourages students from speaking out against a teacher’s’ beliefs: whether it be grades, authority, or just public opinion. American Literature Honors is a class geared towards the Sandlers of the world — junior Dara Woo believes that it cultivates open discussion. She has found it a great platform for her and other students to express their ideas — especially in her class, she finds that whenever the teacher wants to express a controversial idea, they ask the students to discuss it first.

While Tanabe faces students that struggle with her enforcement of critical thinking, Sandler appreciates teachers’ efforts to challenge students and enjoys conversing with them. He makes it a point to visit most of his old teachers as often as he can and he has never developed a poor relationship with a teacher because of his active participation. Ever since he was a child, Sandler has talked to his parents, his friends and his teachers about the same topics in the same way.

And while fear doesn’t rule his participation, practicality does. Sandler usually tries to assess the value of his contribution — will it be a helpful note or a waste of class time? Having taught JAVA classes for MV Robotics on a ten-person team, Sandler understands the stress of teaching and leading a class. He even notes that in the past, he has detracted from class time.

“I was very distracting in [freshman Biology] because I asked questions that went on completely random tangents that weren’t very relevant in the class,” Sandler said. “If a class was full of me’s it wouldn’t go well for the class, but as long as it isn’t I think it’s fine being that way.”